Two purple-haired women are wrapped around a pole that is part-stripper, part-IV. They are jointly intubated; futuristic biomedical equipment sprouting baby bottles and pacifiers pipes its contents into one of the figure’s clear platform shoes. The sci-fi scene is a sculpture by Cajsa von Zeipel, a Swedish artist who makes life-size femme and nonbinary personages out of silicone.

Often equipped with futuristic tech wearables, they seem to merge with their devices, pets, clothes, modes of transportation, and one another. This particular sculpture, X Plus X Equals x, 2021, is an allusion to CRISPR technology, a type of genome editing that some scientists say could enable same-sex couples to have genetic offspring.

Von Zeipel is one of a number of contemporary artists who are embracing the cyborg as a subject. From biotechnologies that rewrite experiences of embodiment to cellular devices that act as cognitive prosthetics, we are all, to one extent or another, cyborgs.

This claim is not novel: philosopher Donna Haraway made it in 1985 in her deeply influential essay A Cyborg Manifesto. While many of her feminist peers outright rejected new technologies because of their association with the military, patriarchy, and capitalism, Haraway proposed that the cyborg could productively destabilize artificial binaries like those separating human from machine, physical from virtual, and being from becoming.

As contemporary artists grapple with what it means to be a cyborg today and imagine what it may mean to be one tomorrow, Haraway’s cyborg feminism has remained a touchstone: a framework to celebrate, expand, and challenge. Some artists see the cyborg as a failed figure that—in light of its embrace by neoliberal transhumanists and its embeddedness in the extractive practices that make tech tick—is less productive than metaphors derived from nature. (Haraway herself has since moved toward “companion species” and “critters.”) There are also those for whom the cyborg is a frightening emblem, representative of feelings of alienation from our bodies or concerns about how humans might fare in the singularity.

“What we have now is a combination of the fictions and myths with the overriding fear of being taken over by machines, rather than welcoming a possibility of collaboration,” says San Francisco-based artist Lynn Hershman Leeson, whose work explores both the creative and destructive potential of technology. Having explored the subject of cyborgs since the 1960s, she just finished a film created collaboratively with GPT-3.

Charlotte Kent, an associate professor of visual culture at Montclair State University, notes that cultural interest in the cyborg predates even Haraway. She points to the period between the world wars, when the cyborg gained relevance amid scientific and technological advances, audiences’ growing enthusiasm for science fiction, and soldiers’ treatment of war injuries with plastic surgery and prostheses.

That the hybridized cyborg is not a new—or uniquely Western—concept is central to Iranian artist Morehshin Allahyari’s work regarding female and nonbinary jinn, or human-creature hybrids from Persian and Arabic mythology. Allahyari’s The Laughing Snake, 2019, was included in “Refigured” at the Whitney Museum earlier this year, a group show exploring the porous boundaries between the physical and virtual selves.

The Laughing Snake comprised a mirrored installation that housed a 3D-printed sculpture of a humanoid serpent (a jinn from a 14th or 15th century Arabic manuscript) as well as a touchscreen through which gallerygoers could access a related story. In a 2023 interview, Allahyari described jinn as a cyborgian mix of human and nonhuman.

Kathy Grayson, founder of the art gallery The Hole, recently mounted “Fembot,” a group show considering predominantly femme bodies in the digital realm. She sees the artistic discourse around the cyborg and feminism as an evolving one. “Early cyberfeminist art was more optimistic; Mariko Mori or Pipilotti Rist were thinking about avatars and digital disembodiment as empowerment, and that is a strong thread today,” says Grayson. “But I think unseen manipulation and control across digital platforms are becoming the subject of works as well.”

Guided by a “crip-technoscience methodology,” artist Erika Jean Lincoln’s DIY-style installation Neural Knot: Synaptic/Semblance, 2023, was on view in “Fembot” at The Hole. By inserting contact microphones into a knotted mass of thread and wire—a visualization of neural pathways—that she suspended between spooled threads on motorized winders, Lincoln both simulates her experience of sound as someone with Audio Processing Disorder (APD) and frames APD as a form of sound art. Logging the sound visually, an associated computer interface acts as a perceptual prosthetic that offers viewers another way into sonic experience.

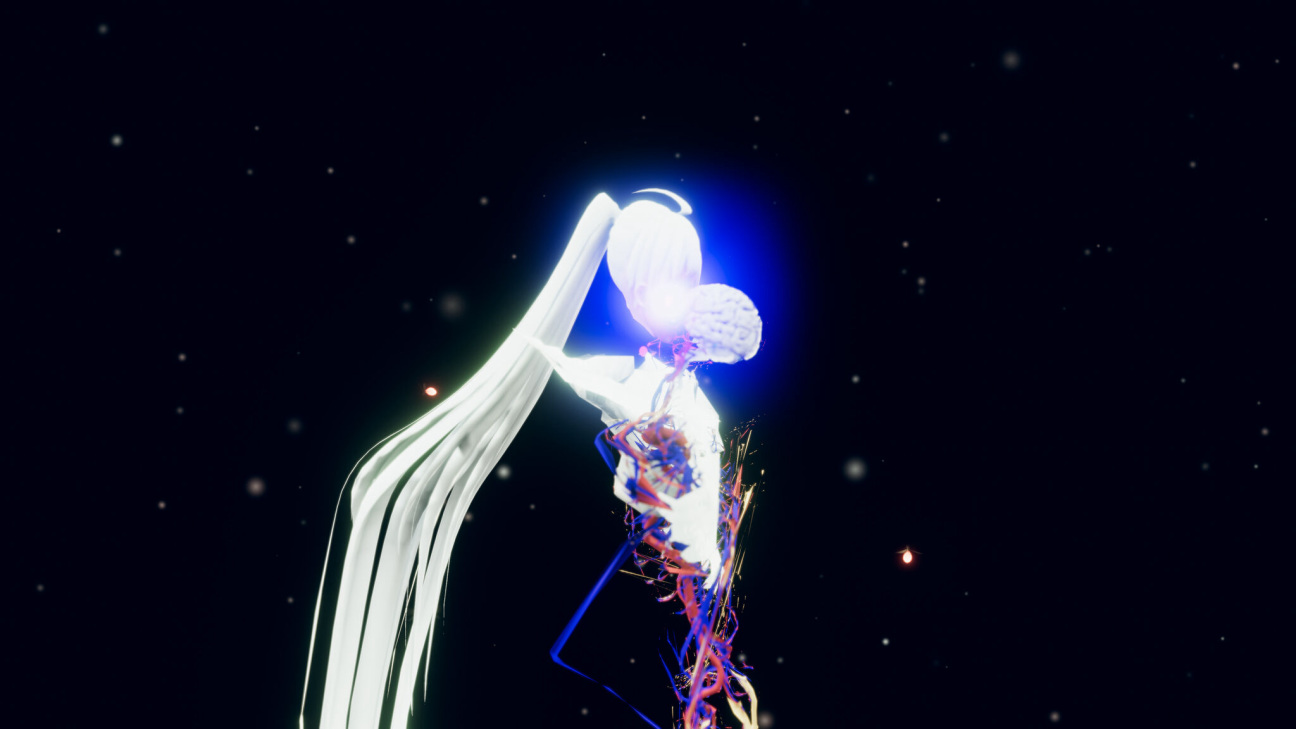

New York-based artist Rachel Rossin is also interested in the effects of technology on our sense of embodiment. Inspired by brain-computer interfaces, The Maw Of, 2022–ongoing—versions of which were presented in “Refigured” and in Rossin’s overlapping solo show “SCRY” at Magenta Plains—unfolds across virtual reality, augmented reality, video, and the Internet.

Using a VR camera with thermal vision (often associated with military operations), Rossin casts herself as a spectral avatar whose brain and skeleton are intermittently revealed as she floats in open virtual space or sprints through a suburban neighborhood. Avatar and flesh, virtual and physical, and domestic and military are enmeshed in a hallucinatory theater. Meanwhile, Rossin’s paintings address the eschatological undertones in our thinking about technology: the foreboding canvases depict armored cyborgs, some labeled “good” or “bad.”

While technology can certainly elicit such binary responses, some queer and trans artists are drawn to the figure of the cyborg because of the challenges it poses to binaries, fixed states, and enculturated notions of “the natural.” Artist and performer Juliana Huxtable, a Black trans woman who was born intersex, identifies as a cyborg. In addition to scrambling the registers of sex and gender, this chosen identifier embraces the mutability, multiplicity, and capaciousness that have characterized some of Huxtable’s experiences of identity in virtual space.

Huxtable, like Allahyari, has found the intersection between human, animal, and myth to be a generative site. When faced with questions regarding the intersection of gender, race, and representation, “it’s more interesting to just go trans-species,” Huxtable said in 2019. “AKIMBO SPITTLE,” her exhibition at Project Native Informant in late 2022, was composed of paintings populated by colorful femme figures that were ecstatically clawed, hoofed, and winged.

Approaching the cyborg as a fruitful site to think about the the present and futurities, scholar Alison Kafer has advocated for “bringing a disability consciousness to the cyborg.” For the titular work of Itziar Barrio’s solo show “did not feel low,” was sleeping at Smack Mellon this spring, the artist, whose recent projects parse technology, labor, and the body, collaborated with Laura Forlano, a social scientist with Type 1 diabetes.

In Hacking the Feminist Disabled Body, Forlano writes about her reliance on, collaboration with, and friction with embedded medical devices, unpacking “the rituals and the mess of data and devices when juxtaposed with human systems in the everyday life of a cyborg body.” Forlano provided daily data from her smart insulin pump, which the pair used to program subtly animatronic sculptures made from concrete and spandex.

Reflecting on A Cyborg Manifesto in 2015, scholar Zoë Sofoulis asked: “What kinds of knowledges about whose material lives and aspirations have input into formulating the metaphor? And what kind of political work do we want our cherished metaphors or monsters to perform?”

For the artists whose work is electrified by these questions today, the cyborg can be a powerful assertion of self, a locus of connection, and a site from which to imagine—or even hack one’s way into—a technologized condition that feels liberating and connective rather than surveillant and extractive. At the same time, the cyborg is an ambivalent, quotidian, even boring creature: that organism who puts on her contact lenses and takes to the computer’s infinite scroll, her body slumped in the chair like an afterthought.