Frank Stick was in search of two things when he arrived on the Outer Banks in the 1920s: adventure and money. He found enough adventure to fill a lifetime but like many Bankers on the isolated barrier islands, he scrambled to pay the bills. Once one of the largest landowners, with property from Kitty Hawk to Hatteras, the artist turned developer lost many of his holdings during the Great Depression. Stick eventually recovered and developed the much-admired Southern Shores community with his son David and other partners. A complex man of shifting interests and unwavering opinions, Stick was both a conservationist who played an instrumental role in the formation of Cape Hatteras National Seashore and an avid land speculator who wrote of turning the Banks into a playground for tourists.

This is his story.

Chapter 5: Southern Shores

Frank Stick was now in his sixties and approaching retirement. He had managed to right the family’s finances by selling his remaining real estate and keeping to his steady work habits. There was even enough money for he and Maud to spend winters in Florida, first at San Carlos Bay, near Fort Myers Beach, and later in Key West. Still, Frank worried about building a nest egg and, as always, kept an eye out for opportunities.

One surfaced in 1945 when Walter J. Townsend, a shipping magnate from Bayonne, New Jersey, considered selling 2,700 acres he owned just north of Kitty Hawk — his only investment on the Outer Banks. The tract ran from ocean to sound and included four miles of pristine oceanfront and even more shoreline fronting Currituck Sound and Ginguite Bay. Long ago, a sand wave had washed over the flat beach and sculpted a series of terraces and gradually rising slopes that elevated the profile from beach to sound.

At $30,000, the price was considered extraordinary and was well beyond Frank’s reach. But he believed the area was promising; developers were busy filling up Nags Head and Kill Devil Hills and would eventually look north for more land. He approached friends for help and offered Townsend an option on the four miles. Townsend’s secretary officially accepted. But then Townsend began having second thoughts. Sensing that his land was worth even more, he declined to go through with the sale and failed to respond to letters Frank wrote.

Frank turned to his son-in-law, attorney John McMullan of Elizabeth City, who sued Townsend for failing to exercise the contract. McMullan won at trial and then on appeal. Frank rewarded his son-in-law with a one-third interest in the property. McMullan suggested that his law partner, N. Elton Aydlett, and Aydlett’s brother, Cyrus, a successful realtor/investor, cover the $30,000 option in return for another one-third interest. A partnership was born, with Frank in charge of managing the design and construction.

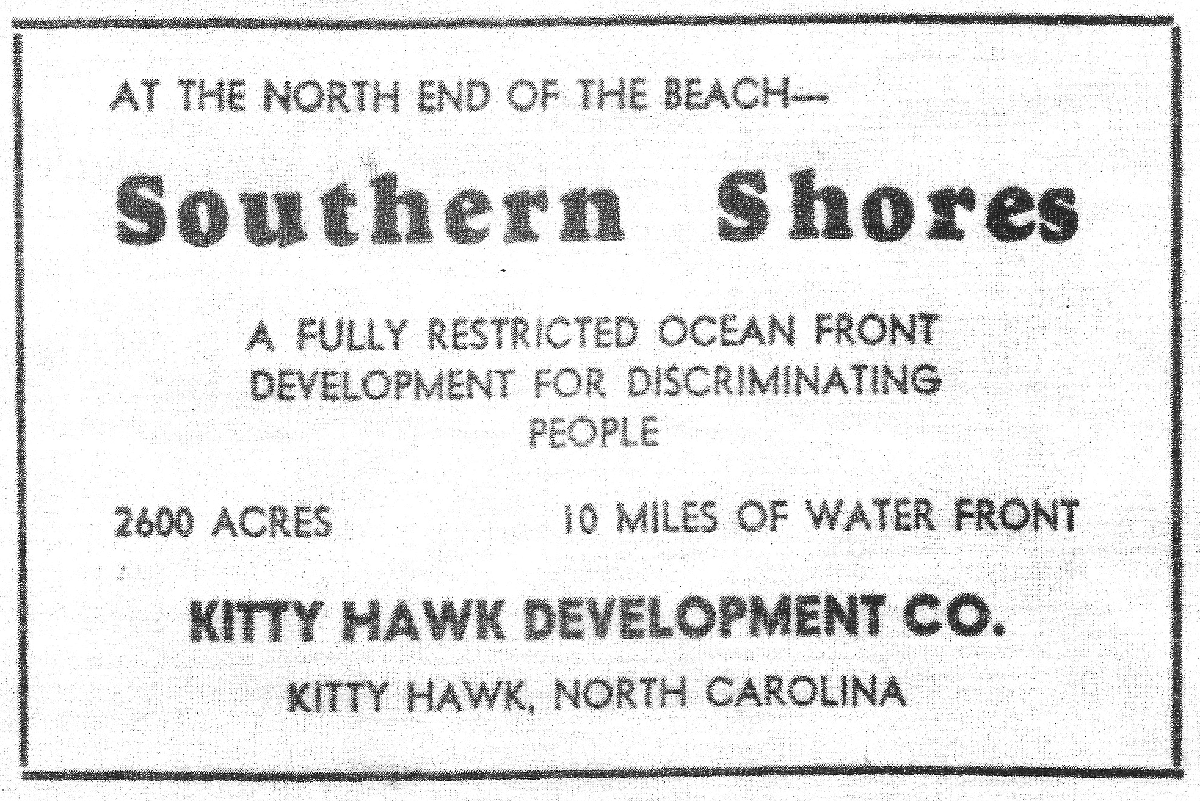

The first order of business, choosing a name, proved problematic. Frank and his partners bounced around possibilities, finally settling on Southern Shores. Frank had hoped for something a little artier that captured his plan to build a communal kind of resort that appealed to artists, writers and vacationers of all economic stripes, not only wealthy outsiders. The name was also geographically confusing. The four-mile tract near the Wright Brothers Memorial Bridge served as a gateway to the northern beaches of Duck and Corolla, and wasn’t part of the Lower Banks. An advertisement even stressed its location “At the north end of the beach – A fully restricted ocean front development for discriminating people.”

Frank got busy laying out the streets along the oceanfront, with a paved road, Ocean Boulevard, running north to south and side streets positioned east to west. Lots were set in 50-foot increments. However, customers were required to buy two lots at a time, or 100 feet of frontage. Instead of a la carte pricing, Frank introduced fixed-pricing that included the lot, site preparation, and house. Using his skills as an artist, he gave each potential owner a handsome sketch of his house.

One of the earliest buyers was Huntington Cairns, a polymath from Washington, D.C., who had gone directly to law school after high school, skipping college, and spent his spare time studying Plato and Shakespeare. In addition to his work as lawyer, Cairns wrote books across such diverse subjects as philosophy and journalism, including a biography of his old friend, Baltimore writer, H.L. Mencken. For years, he served as secretary and general counsel for the National Gallery of Art, and as an unpaid adviser to the Treasury Department, judging whether Post-War art arriving in America should be considered pornographic. Unsurprisingly, Huntington and Frank hit it off and Frank built Cairns a cottage next door to an oceanfront house Frank built for himself. The Sticks and Cairns often shared dinners with an array of famous and not-so-famous writers and artist friends of Huntington. Cairns called Southern Shores his second Eden and later retired there.

Building affordable housing during the war years had influenced Frank’s thoughts on style. So, too, the simple low-slung bungalows that Frank saw in Florida, At Southern Shores, Frank merged these influences in a signature new Outer Banks bungalow known as a Flat Top – a single-story, whitewashed block bungalow with a flat roof. The design was driven in part by a shortage of building supplies following the war. Many of the usual supplies, wood and steel, weren’t available. Frank and his Hatteras buddy, Curtis Gray, formed a company, Kitty Hawk Concrete Products, and used sand they carted off the beach (illegal today) to manufacture concrete blocks.

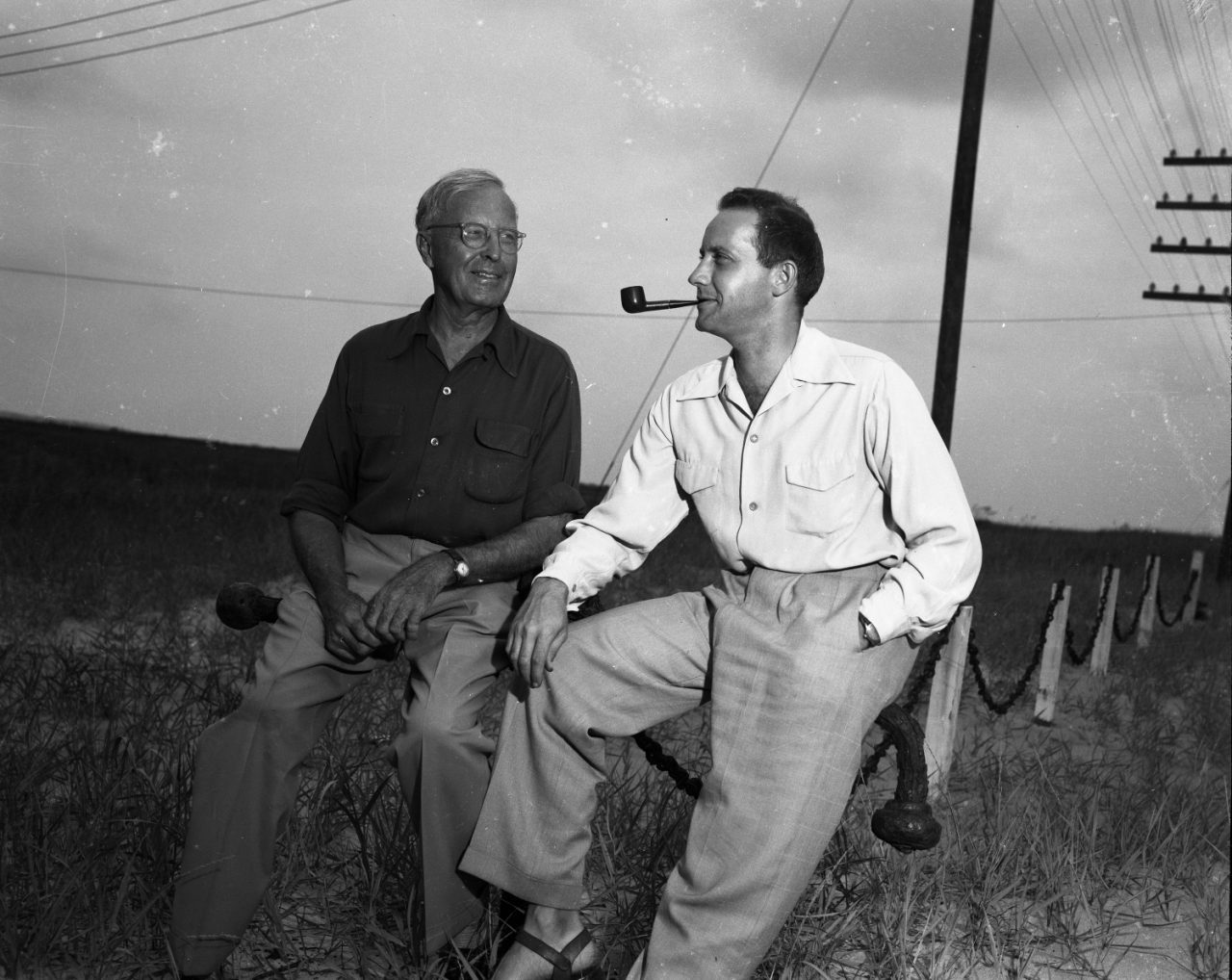

According to the architecture writer Marimar McNaughton, “A Flat Top house took roughly four months to build and cost one-third less than a traditional home.” Nevertheless the Southern Shores partners sold only one house in 1947 and Frank was forced to take on the role of salesman, reaching out to a long list of friends and associates. He also turned to his son David, then working in New York City as an editor, to come help.

For the next few years, the Sticks concentrated on the oceanfront, slowly filling in scores of lots and developing new sections. Meanwhile, the land along the sound and scruffy upper terraces remained untouched because it was thought to be worthless. It would be David who saw the value of extending Southern Shores, laying out lots and roads, digging lagoons, adding a marina, golf course and freshwater lake, turning Southern Shores into a destination for retirees and year-round Bankers, as well as an oceanfront resort.

But even as the business was beginning to show a profit, the working relationship between Frank and David soured. There were scuffles over responsibilities, salaries, and business philosophies. David resented the way Elton Aydlett seemed to question his every decision, and more than once threatened to quit.

Some of the tension was likely the normal back and forth between fathers and sons. But the disagreements also felt personal at times. Frank could be impatient and controlling and may not have given David enough credit for his good work. “Tact was a trait for which Dad was never noted, nor am I,” David once observed.

One of the issues was that Frank was growing restless once more. Southern Shores was moving along and he wanted more time for himself, for Maud, and for his beloved art. He had begun painting again and wanted to do more than illustrations; he wanted to leave something lasting for his family as his legacy. In the 1950s, Frank also began visiting the island of St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands, and being Frank Stick, he of course had ideas.

In 1952, Frank formed a new partnership with John McMullan and the Aydlett brothers and purchased 1,600 acres of the old Lameshur Sugar Plantation overlooking Cruz Bay on the island’s south coast. The goal was to develop an exclusive mountainside resort or, alternatively, restore the property and “make a quick and profitable turn-over,” Frank wrote. It never worked out. Money was short and the investors had trouble finding equipment and workers. In 1954, Frank wrote that he had had an epiphany: Instead of building a resort, why not set aside the land as part of a national park, like he had done on the Outer Banks. Frank donated his share of the land and sold the rest at cost for the park. Working with the financier Laurance Rockefeller, who owned property on the north coast, Caneel Bay, and his old friend, Conrad Wirth, of the National Park Service, Frank helped plan the Virgin Islands National Park.

That same year Frank informed his partners that he was retiring. He was 70. While he would continue to give advice to David and help to mediate the growing disagreements between David and Elton Aydlett, Frank used most of his time to travel and paint. He died in 1966, at the age of 82, and was buried in Kill Devil Hills.

After Frank’s death, David continued to develop the soundside at Southern Shores, digging channels to the Currituck Sound and interior ponds to help drain swamp land for building. Planning began for a separate development-within-a-development known as Chicahauk, with canals and open space nestled among the coastal dunes. Sales increased. Nevertheless, David was saddled with debts and “almost on the verge of bankruptcy,” he would later recall. In 1976, he agreed to sell Southern Shores for $2.1 million to Walter Royal Davis, a flamboyant character who had grown up poor near Elizabeth City but gone on to make millions hauling oil in the Texas Panhandle. Davis turned the job over to a talented landscape architect named Charles “Mickey” Hayes Jr. who finished Southern Shores and then designed the exclusive Currituck Club in Corolla.