A poster-painter up a ladder daubs a likeness of a Bollywood heroine on a cinema facade, oblivious to a riotous mob, cudgels raised, stripping a man below the waist to determine his religion. The chillingly counterpointed scenes, in blood reds and livid greens, are in “City for Sale”, a large-scale oil painting by the Indian artist Gulammohammed Sheikh. Made in Baroda, Gujarat, in the early 1980s as pogroms against Muslims engulfed his home state, the artist’s anguished wake-up call has hung largely unseen in a backroom of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London until now.

The monumental painting is among the surprising works on show in Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now, at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes until January 28 (then at The Box in Plymouth). Curated by Hammad Nasar and Anthony Spira, this rare exhibition juxtaposes exquisite traditional miniatures from sacred and secular texts (some so light-sensitive they can be shown only once every 10 years) with modern and contemporary works they inspired, from sculpture to film and installation. A complex story of art, imperial power and cross-cultural encounters emerges through 180 works, tracing how (as in Iran) a courtly tradition that flowered in Mughal, Rajput and Deccani royal workshops before the 1700s still captivates and challenges cutting-edge artists (of various heritages) today.

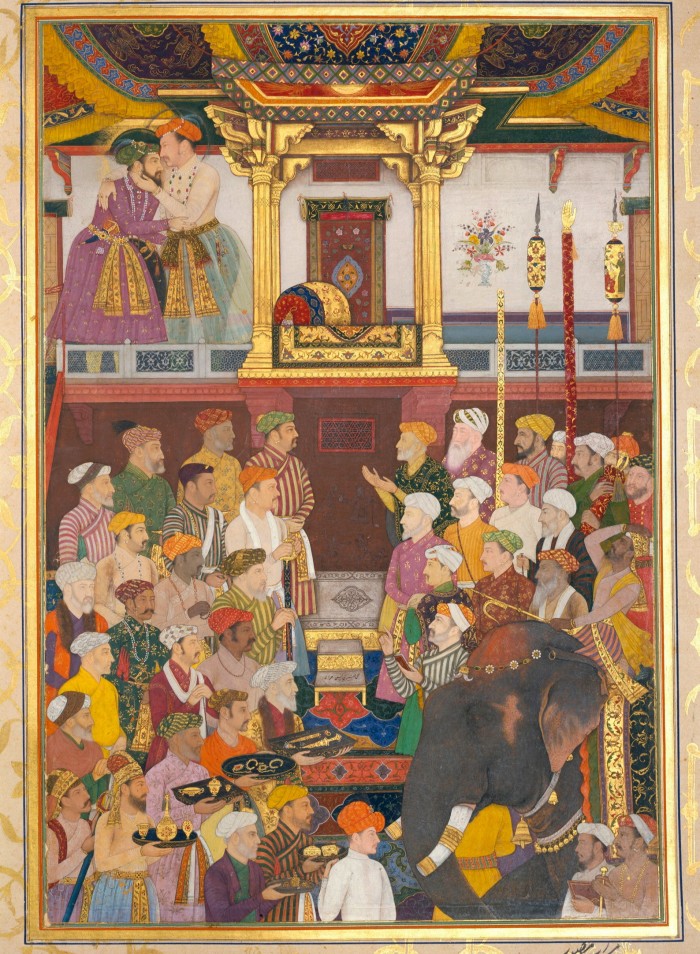

The first of five thematic sections begins with sumptuous folios from the Padshahnama (1656-7), its processional elephants splendid in watercolour and metallic paint. This Mughal chronicle was gifted to King George III as British power waxed in India. Some folios are by signed artists such as Murar, who portrayed himself in a corner. The Dutch artist Willem Schellinks copied another album (also studied by Rembrandt) for his drawing “Shah Jahan hawking” (c1657-60). William Morris and the avid Indian miniature collector Howard Hodgkin hymned the Persian epic the Hamzanama. Yet the hot colour-fields of Hodgkin’s small oil-on-wood abstract paintings rather invite comparison with Rajput miniatures placed nearby: “Radha and Krishna” (c1730-35), attributed to Manaku, with beetle-wing cases glued on as emeralds.

In the catalogue essay Emily Hannam, adviser to the exhibition, writes that there are “tens of thousands” of such works in public collections in Britain. The show’s radical premise is that south Asian miniature painting is an “important but overlooked area of British art history”. While East India “Company School” artists pandered to European tastes, the mass export of highly portable historic works — as diplomatic gifts and purchases or as plunder — nourished European art yet sundered generations from a vital inheritance.

Both Sheikh and Pakistani artist Zahoor ul Akhlaq studied at the Royal College of Art in the 1960s, and were astounded by the V&A’s originals after muted reproductions at home. Sheikh’s work “changed in London”, Nasar writes in the catalogue, as the artist, in his own words, discovered “treasure after treasure”. His large urban canvas might seem to owe nothing to the tiny, intricate landscapes and interiors on the handmade paper known as wasli. Yet their multiple scenes in a flat plane, with frames that draw in the viewer and elements that spill out of borders, pose beguiling alternatives to Renaissance fixed-point perspective. As Sheikh noted, such art, stemming from a world in flux, demands of the viewer an “active participation rather than cool contemplation”. By contrast, Akhlaq was more fascinated by miniatures’ formal aspects than narrative possibilities, deconstructing them in acrylic paintings such as “Untitled (2)” (1990): a gestural blue horse viewed through a window frame.

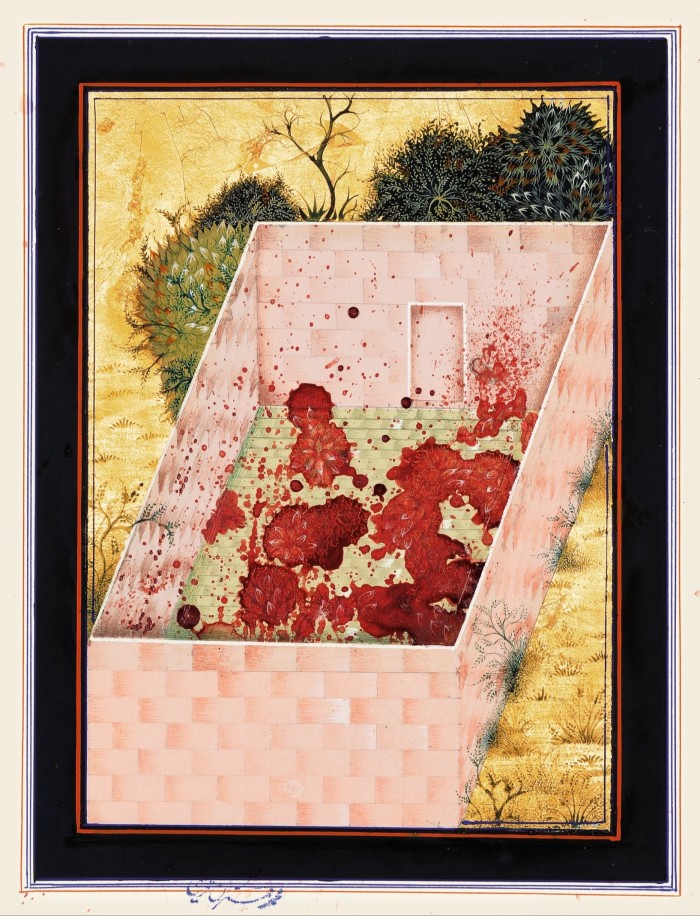

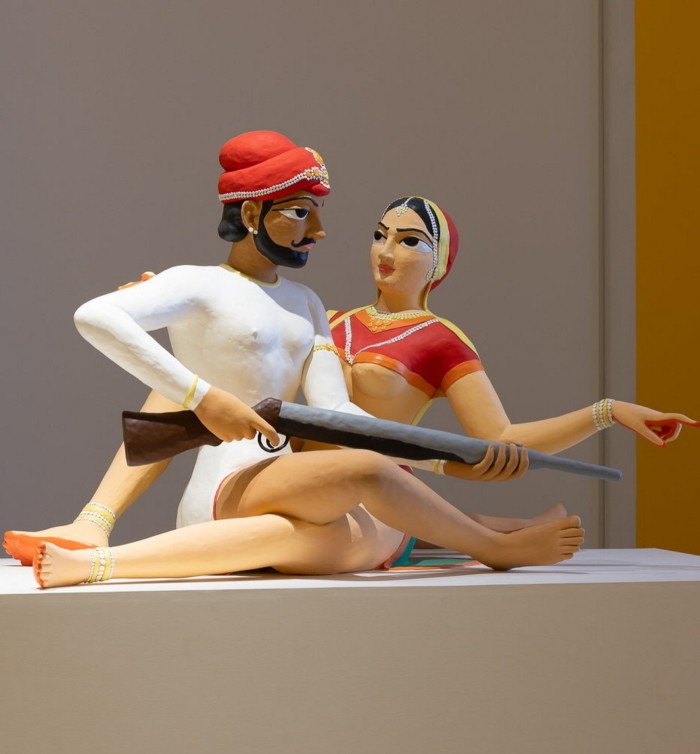

Akhlaq created a seminal department in 1985 at the National College of Arts in Lahore (founded by Rudyard Kipling’s father) that still nurtures stellar alumni. Among those on show is Imran Qureshi, globally renowned for his large-scale installations. The red splatter and gold leaf of his painting “Blessings Upon the Land of My Love” (2011) reference both terrorist violence and traditional hunting scenes — notably “Wild animals are let loose” (c1840), with its blood-red, almost floral spray. In the intimately panoramic “The Scroll” (1989-90) by New York-based Shahzia Sikander, another Lahore alumna, a woman in white wafts through interiors. Such feminist reclaiming echoes throughout the show. In Hamra Abbas’s resin sculpture “Lessons on Love” (2007-8), a moustachioed prince makes acrobatic love while grasping a hunting rifle — an absurdist lampooning of martial values and courtly erotica.

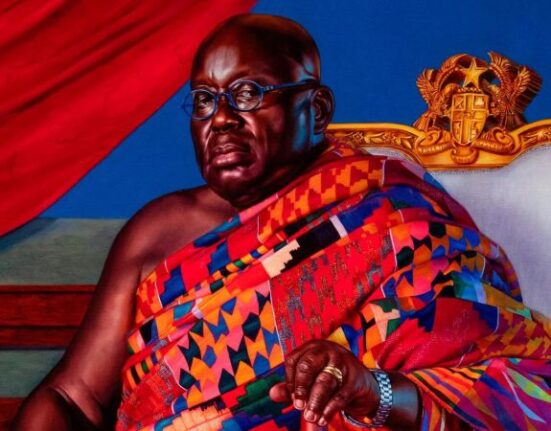

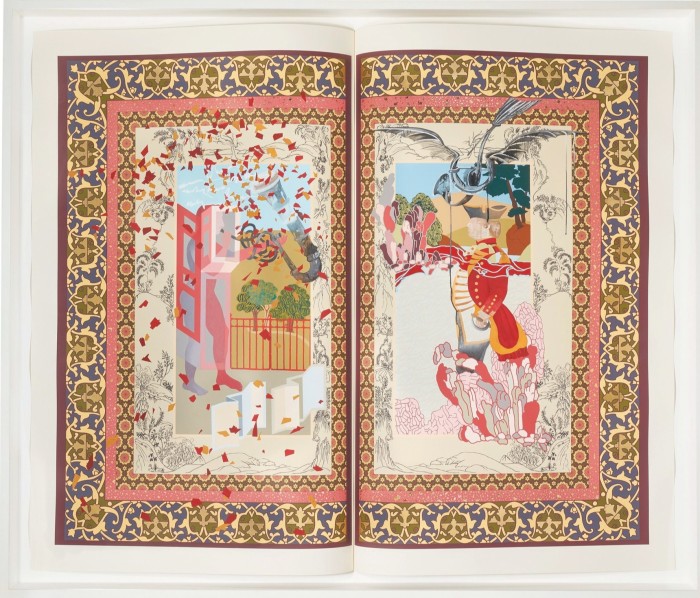

Abanindranath Tagore, nephew of the Nobel poet Rabindranath, pioneered the neo-miniaturist “Bengal School” in the 1900s, whose anti-colonial thrust also finds echoes. Sikander’s “The Explosion of the Company Man” (2006) defaces a colonial officer in a diptych resembling an outsize album. Abbas’s four-panel installation “All Rights Reserved” (2004) raises ironic questions about ownership and access with reference to King of the World, a selective 1997 tour of the Padshahnama (now owned by King Charles III). In her take, the bearers from “The delivery of presents for Prince Dara-Shikoh’s Wedding” (c1640) are poignantly detached from their gifts.

Artistic homage often proves ambivalent. Rashid Rana’s irreverent “I Love Miniatures” (2002) appears to be a pixilated portrait of a Mughal emperor, but is a digital composite of advertising billboards — mocking the viewer’s expectations of both work and artist. Repurposing princely art, Qureshi’s painting “The Artist’s Younger Brother” (1995) portrays his sibling in profile in retro mauve flairs. Yet the Liverpool-based Singh Twins’ “past-modern” style both adheres to and expands tradition. In “Because You’re Worth It? II” (2022), a digital fabric lightbox that impugns consumerism and ecological disaster, death rides a composite elephant made of brand logos.

The most compelling section combines portraiture with politics in the wake of the September 11 attacks. Nusra Latif Qureshi’s “Did You Come Here to Find History?” (2009), a nine-metre scroll of digital prints, is a disturbing, fragmented palimpsest of Venetian and Mughal portraits superimposed with the artist’s passport photo. Karkhana (2003), a collaborative series of 12 small paintings, was inspired by, and named after, the Mughal workshops. Qureshi and five other Lahore alumni each added elements before couriering the works on around the diaspora. Recurring images of stamps and maps reflect anxiety about a post-9/11 world where would-be travellers are harassed at frontiers.

The Order of Things, a section that shows the work of Company School naturalists alongside ironic rejoinders, has the fruit of another collaboration. In The Gardens of England (2017-23), David Alesworth, a British artist who lived in Pakistan, worked with Shakila Haider, a Lahore-based miniaturist, to reverse the coldly classificatory gaze. Among watercolours based on Alesworth’s photographs are surreally clinical images of “exotic” flora in Milton Keynes.

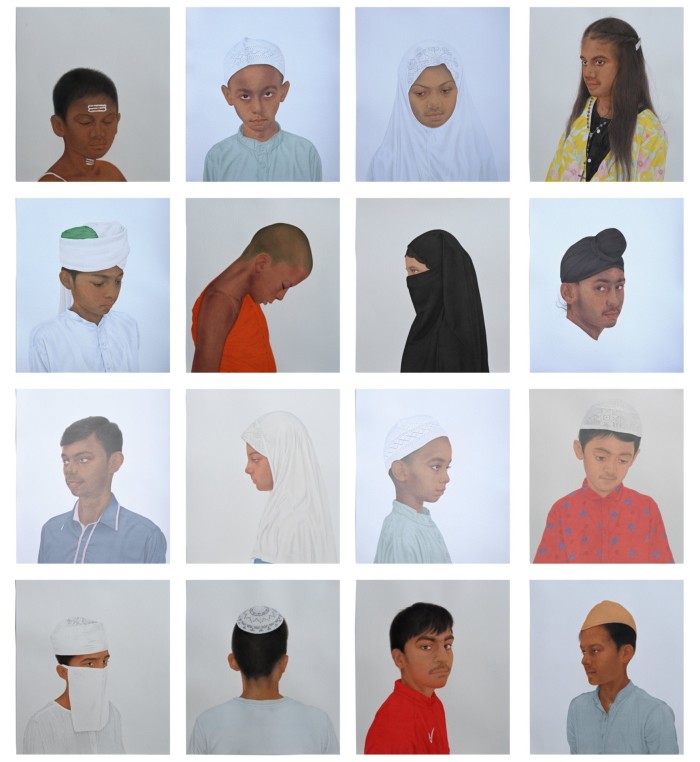

Similarly, the ethnographic floating heads of “Forty-one portraits” (c1780-1800), made in West Bengal, are subtly subverted in Ali Kazim’s tenderly observant Children of Faith (2023) series, and Abbas’s Every Color (2022): tiny portraits of transgender Lahorites painted on silk. Appearing to peep through the cloth, these faces force the viewer up close in an act of intimacy and recognition that speaks volumes about the miniature’s enduring power.

To January 28, mkgallery.org

The Box, Plymouth, February 17-June 2, theboxplymouth.com