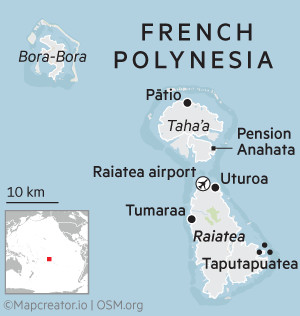

The little island of Raiatea is believed to represent a sacred heart of Polynesia and the Pacific. Look at it on Google Earth and you can start to understand this logic.

Raiatea is 12 miles long, with a spine of green mountains and a barrier reef extending all around it like a halo. Pan backwards on the satellite imagery, and you see the island indeed lies in the middle of the world’s greatest ocean. It soon shrinks to a solitary green pixel in the expanse of the Pacific: with Raiatea at its centre, this view of the globe appears almost totally blue.

Should weather systems obscure New Zealand, or advancing dusk conceal Baja California, this face of the planet could be mistaken for Neptune: a world marbled by undersea trenches, textured by swirling currents. Viewed from the Earth’s atmosphere, a pinprick island in the sea appears as slight as a star beyond the rim.

In his 1992 book The Happy Isles of Oceania, Paul Theroux described the archipelagos of the Pacific as being “like a universe . . . a chart of it looked like a portrait of the night sky”. In this, and other ways, such islands seem to have a closer kinship with celestial bodies than the continents on the ocean’s edges. This seemed especially true of Raiatea, for its name translates as: “faraway heaven” or “the sky with soft light”.

Raiatea lies within the Society Islands of French Polynesia. Along with its sister island Taha’a, it offers visitors a window into south Pacific life — quieter than Tahiti, an hour’s flight to the east; less cocooned than the resorts of Bora Bora, visible on the north-western horizon. Raiatea and Taha’a, with a combined population of about 17,000, were described to me by one local as being in a category of islands where “people still wave to passers-by”.

Raiatea’s interior is defined by volcanic mountains — vertical, verdant summits on which you can find a species of white flower that grows nowhere else. Lining the shore are about a dozen villages, where bungalows with corrugated iron roofs chime like glockenspiels during tropical downpours. There are also peach-coloured Protestant churches; kitchen gardens of breadfruit and taro; hedges of hibiscus and gardenia. Surrounding Raiatea is a lagoon of water so translucent that to float on it feels like a kind of levitation. I spent a week on Raiatea and in its orbit, sailing, swimming, snorkelling and kayaking in the waters of the lagoon. I saw that it is indeed a heavenly place. It is also an island intimately associated with the art of navigation — and the alchemy of mapping the Earth.

The first maps I saw there were shipping charts — spread on the galley table of a catamaran by its captain, Terehau Doudoute. We were midway through a two-day circumnavigation of Raiatea: Terehau had dropped anchor and was now sketching our course with an index finger. He identified the motu — palm islets strung along the barrier reef like beads on a necklace.

He tapped a knuckle where freshwater inlets ebbed towards corals among which rays and reef sharks swam. Mostly his attention was directed to the “passes” — gaps in the reef connecting the turmoil of the Pacific to the sanctuary of the lagoon, through which boats made passage in and out of Raiatea. Most of the time the breakers on the barrier reef were audible off to our port side, the powerful waves arrested at the horizon as though at the hand of Canute. But in eight places they intruded: the ink-dark Pacific spilled into the aquamarine lagoon. When the boat pitched and yawed, it was a sign a pass was near.

“Some passes can be dangerous,” said Terehau. “Some passes you have to check the wind and the tide before you enter. One pass is sacred.”

He pointed to the pass of Te Ava Mo’a on the map. This pass once served as a ceremonial gateway to Taputapuatea, a temple complex on Raiatea’s eastern coast. The temples here, known as marae, are relics of a time before European sails were sighted, in the 18th century. Taputapuatea counts among the most significant archaeological sites in Polynesia: it is what makes Raiatea a holy centre.

The next morning I stepped ashore to explore the ruins. Crabs scuttled about courtyards shaded by banyan trees where chiefs in red feathers were invested by priests, and islanders from distant archipelagos came to pay tribute to the resident gods. Waves lapped against foundation stones, and coral altars seemed to be oriented to the distant thunder of the barrier reef. Some historians have claimed that marae such as Taputapuatea were places of human sacrifice.

Raiatea has been identified as the “Hawaiki” of Polynesian mythology — a central homeland from which seafarers set out to colonise the three points of the Polynesian Triangle over a period from around AD400-1400. These seas were the last swath of the planet to be settled by humankind, and though much is unknown (for nothing was written down), the sea voyages made from the sacred pass were probably among the greatest in the history of migration.

The canoes of the old navigators were small, the leagues ahead of them metaphysically vast. But there was a traditional way of conceiving this geography. An information board near the ruins outlined an ancient Polynesian vision of the ocean as an octopus. The head was Taputapuatea, the journeys made were the tentacles. One tentacle stretched 2,500 miles northward to the black sand beaches of Hawaii. Another probed some 2,700 miles eastward to the treeless shores of Easter Island. A third trailed 2,500 miles south-west to New Zealand.

In the 21st century, these same journeys are being made in reverse. Maori and Hawaiian pilgrims come to Taputapuatea to stand where their ancestors may have done, and leave shell necklaces and other votive offerings. When I returned to the catamaran, Terehau told me that everyone on Raiatea was Christian today, but the marae were still respected. Across Raiatea I heard people linger reverently on the words: “les anciens navigateurs”.

“Everything they needed to settle an island — pigs, chickens, plants — they would have carried in their boats. And they navigated by the stars.”

In 1769, a different kind of boat sailed through the Te Ava Mo’a pass: the HMS Endeavour. Captain James Cook was the first European to visit Raiatea: he arrived with one eye on the heavens, another on the Earth. Cook was in the Pacific to observe the transit of Venus (an event that, it was hoped, would help measure the distance of the Earth from the sun).

He was also under instructions to locate and map a mysterious southern continent (which he did not find). In any case, he found an accomplice in his mapmaking. Tupaia had been a priest at Taputapuatea — a proud, tattooed man in his forties, he had inherited a knowledge of islands spread across millions of square miles of ocean. On his back was a battle scar from a spear tipped with a stingray barb.

Tupaia was fascinated by European maps — the idea that a bird’s-eye view of the world could be expressed by ink on paper — and made early experiments in mapmaking drawing the passes of Raiatea. Cook, with initial reluctance, accepted Tupaia on board Endeavour as his guide. The result of their collaboration was Tupaia’s Map — a landmark document depicting some 74 Pacific islands known to the priest, illustrated with tiny sailing ships. A few of Tupaia’s islands were in the wrong place, others may have been mythical islands and have never been located. Everything became murkier the further you went from Raiatea, which was the centre of the map.

Nonetheless, Tupaia’s Map marked a watershed in European exploration of the Pacific. It is a testimony to the skills of the Polynesian navigators — who measured their journeys in days rather than miles; who discerned clues from the temperament of the waves and behaviour of clouds; who remembered islands their forebears visited generations before, reciting their names as though lines in a poem. European maps were cold, objective documents, but their Polynesian equivalents were memory-maps compiled through subjective experience: maps to be felt at the prow of a canoe, rather than read upon a table. Maps that may have also incorporated otherworlds and spiritual realms.

Tupaia sailed with Captain Cook to New Zealand. He was en route to England when he died of dysentery or malaria in present-day Indonesia — beyond the margins of the map that survived him.

Among the smallest features on Tupaia’s Map is Taha’a — a little island two miles from Raiatea, within the same barrier reef. On modern maps it appears in the shape of a flower, with peninsulas as petals. It is, if anything, even more beautiful than its neighbour: acacia forests spill down to blue bays, vanilla farms on the shore face pearl farms at sea. A few luxury resorts lie along its motus — the sort of choreographed paradises where seaweed is tidied from the beaches.

More interesting is the main island, where I stayed in Pension Anahata, a family-run guesthouse. From its balconies, you could observe the rhythms of island life — a bakery van delivering croissants every morning, the school buses leaving at dawn for the Raiatea ferry, the neighbours feeding the fish that shoaled under jetties at twilight. One day, after breakfast, the owner of the guesthouse emerged to show off his private collection of pre-European contact stoneware: axe heads and other objects whose uses would have be known to Tupaia.

Tupaia travelled with Cook, but it was French missionaries who made a lasting imprint on these islands — which today are part of an “overseas country” of France. Boursin is on sale in the local supermarket. Twice I heard a radio playing “La mer” by Charles Trenet. One day I joined a hiking tour into Taha’a’s interior in the company of guide Teva Ebbs. High on a mountainside, he hacked a branch of wild hibiscus with a machete, whittled it into a basic flute and played the opening bars of “Frère Jacques”. There were layers of identity here — people might be considered French, Polynesian or even Tahitian. One took precedence. “France is what is written on the paperwork,” he said. “But it is your island that is written on the heart. It is your island that raises you, that turns you from boy into man.”

We hiked across the lush hills of Taha’a, over ravines where islanders hunt wild pigs by night, among groves of avocado and mango. In the distance we saw the blue waters of the lagoon terminate at the barrier reef: a boundary to the wider world. On the way, Teva talked about the places he had visited. He had stood in the spray of Niagara Falls, seen spaceships in the museums along Washington’s National Mall. He had walked the furnace-hot streets of Dubai and eaten fondue by Lake Annecy. He said many islanders baulked at the notion of Taha’a as a paradise, but it was precisely because Teva had seen the rest of the world that he knew it was true.

Associations of paradise cling to tropical islands — because they are bountiful and temperate, because they are landmasses on a human scale where a world might be remade in miniature. “Paradise” is a word liberally used to describe Thai archipelagos, Caribbean cays — but it has a deeper connection to the islands of the Pacific. Arriving in the Society Islands in 1768, French explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville “thought [he] was transported into the Garden of Eden”. Joseph Banks, travelling with Cook, spoke of “the truest picture of an arcadia . . . the imagination can form”. These islands were among the last crumbs of terra firma to be detected by Europeans. More significantly, they were some of the final territory settled by Homo sapiens: little Edens unmarked by humankind until the 9th century. A last place that recalled the first garden.

That evening I cast off in a kayak from a bay in Taha’a. The night wind fretted the palm fronds on the beach. Far out were the depth-charge booms of the barrier reef. Above me was the greatest and original map: a sky full of bright stars. It was the ascent of stars that guided navigators from the sacred pass at Raiatea, lighting stellar paths across thousands of miles of desolate ocean. With the shadows of the shore behind me, the swish of my paddle beside me, I caught myself dreaming of paradise islands still waiting to be found. But among the shifting constellations I could see fast-moving satellites — their cameras ensuring no corner of the world went uncharted.

Details

Whenever you may be in the world, getting to Raiatea and Taha’a is unlikely to be quick. Paris is the only European destination with connections to French Polynesia’s Faa’a International Airport on Tahiti: Air Tahiti Nui (airtahitinui.com) flies from Charles de Gaulle, stopping at Los Angeles en route. Then from Faa’a, flights to Raiatea take around 45 minutes. Returns cost from about £1,235.

Tahiti Yacht Charter (tahitiyachtcharter.com) offers a private four-day circumnavigation of Raiatea and Taha’a by catamaran, with a captain and onboard chef, from £3,460 for two people. A typical programme includes snorkelling, a shore excursion to Taputapuatea and use of kayaks and paddleboards within the lagoon. Raiatea Lodge Hotel (raiatea-lodge-hotel.com) is set among green lawns on the island’s west coast, with doubles from £325.

The ferry from Raiatea to Taha’a takes 15 minutes (hotels and other accommodation may be able to organise boat transfers). Pension Anahata (pensionanahata.com) is a family-run guesthouse on the south side of Taha’a, with several private bungalows overlooking a sandy beach, bikes to explore the island and kayaks to paddle about the lagoon. The restaurant serves excellent poisson cru (similar to ceviche). Bungalows sleeping two cost from £140, including breakfast. Poerani tours offers hiking and 4×4 tours of Taha’a — contact them via Facebook: facebook.com/poeranitours/.

Oliver Smith was a guest of the tourist board, Tahiti Tourisme (tahititourisme.pf)

Follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen