In recent years, as Hindu nationalists have risen to power in Indian politics, the idea that the country itself is destined to be the vishwaguru, teacher to the world, has gathered currency. Ideologues seek to convince us that the contributions of ancient Hindus in astronomy, yoga, philosophy and mathematics (we invented the zero, don’t forget) predestine India for global leadership. It is even being said that it was not Greece, but India, that was the “mother of democracy”. The recent surge in economic growth is seen as legitimising our status as the guru-to-the-world.

The evidence for these claims of historical pre-eminence is of uneven and unreliable quality. And whether, in the years to come, India will indeed surpass China and the US as an economic superpower is very much open to question. That said, the one area in which India does indeed lead the world is with regard to its proficiency in and passion for the game of cricket.

My country’s acknowledged leadership here is currently being showcased by its hosting of the Cricket World Cup. Now entering its concluding stages ahead of the final on Sunday November 19, the six-week tournament has featured 10 teams from four continents participating in matches held in cities across this vast country. India is now the epicentre of world cricket, having comprehensively displaced the previous claimants to that title, England and Australia.

The first Indians to take to cricket were the Parsis of Mumbai, a modernising community who quickly embraced western music, science and art, as well as western forms of sporting entertainment. A cricket club they established in 1850, the Young Zoroastrians, is still in existence. The game spread to other communities and cities, and by the first half of the 20th century had become the country’s best-loved sport. Xenophobic nationalists demanded that cricket “Quit India” with the British; instead, it has steadily increased in popularity. India’s greatest cricketers are as wealthy and as widely adored as India’s leading film stars.

Cricket’s appeal is aided by the fact that it is the only team sport in which Indians are globally competitive. They have never qualified for a football World Cup. India once dominated world hockey; in recent decades, they have lagged behind European nations and South Korea. India’s medals tally in athletics at the Olympics is one gold in the past century, as compared with 26 golds for tiny Jamaica. On the other hand, India has won two Cricket World Cups, encouraging the sport to become what football never could and hockey no longer can — a vehicle for patriotic pride.

The last time my country hosted a World Cup was 12 years ago, when it was not yet the world’s most populous nation, not yet the world’s fifth-largest economy, not yet seen by the US as a bulwark against the rise of China. The prime minister back in 2011 was the understated and scholarly Dr Manmohan Singh; now it is Narendra Modi, who, combining personal charisma with an authoritarian instinct, is at the centre of a vast personality cult.

The traditional form of the game, Test cricket, had teams playing two innings each over five days, with no restrictions on how long a team could bat. The World Cups are played in an abbreviated form, of 50 overs a side, with matches finished in one day. In the early 2000s came an even shorter format, of 20 overs a side, played in a single evening, thus attracting adults after work and children after school.

Twenty20 cricket was invented in England, but made famous — and profitable — in India. In 2008, a buccaneering entrepreneur named Lalit Modi (no relation of Narendra) started an Indian Premier League competed for by eight city teams, each owned by a private franchise fronted by film stars and industrialists.

Lalit Modi’s sporting and business activities were controversial. Accused of money-laundering and bid-rigging, which he denies, he moved to London in 2010, and has since not come back to India for fear of arrest. Nonetheless, the tournament he helped found has spectacularly flourished in his homeland. Each match has stadiums filled to the rafters, and a live TV audience of up to 100mn. The finest Australian, South African and West Indian cricketers eagerly line up for an IPL contract, emulating the Brazilian, Argentine and Ghanaian footballers who join wealthy clubs in England, Spain, France and Italy. As player fees have risen, so has the income accruing to the Board of Control for Cricket in India, whose revenues approach $1bn a year.

The first three Cricket World Cups, in 1975, 1979 and 1983, were all held in England. Indian administrators then forged a clever alliance with their Pakistani counterparts, prevailing upon the International (previously Imperial) Cricket Council to have the next World Cup held in the subcontinent. The 1987 tournament was co-hosted by the two countries. In 1996 India joined hands with Pakistan and Sri Lanka, and in 2011 with Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. This spirit of co-operation has now been abandoned, with all the matches of the 2023 World Cup being played within India alone.

My country is now the sole superpower of world cricket, exercising a hegemonic influence over how the sport is played across the globe. Because of its financial heft, other cricketing nations give the BCCI a decisive say in the conduct of franchise-based tournaments, the forms of sponsorship, and the scheduling of bilateral series and international competitions. The BCCI takes this deference for granted; in this sphere at least, erstwhile anti-colonialists have become arrogant imperialists.

In discarding its South Asian allies and hosting the present World Cup alone, the BCCI was encouraged by the IPL’s success, and by the growing asymmetry, in economic and geostrategic terms, between India and the other countries of the region. Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh are all marked by political instability; the first two by a failing economy as well. The powerful countries of the west court India assiduously, seeking a greater share of the Indian market while ignoring the Modi government’s dark record on human rights. Political and corporate elites manifest a growing sense of self-importance, which has come to permeate those who run Indian cricket as well.

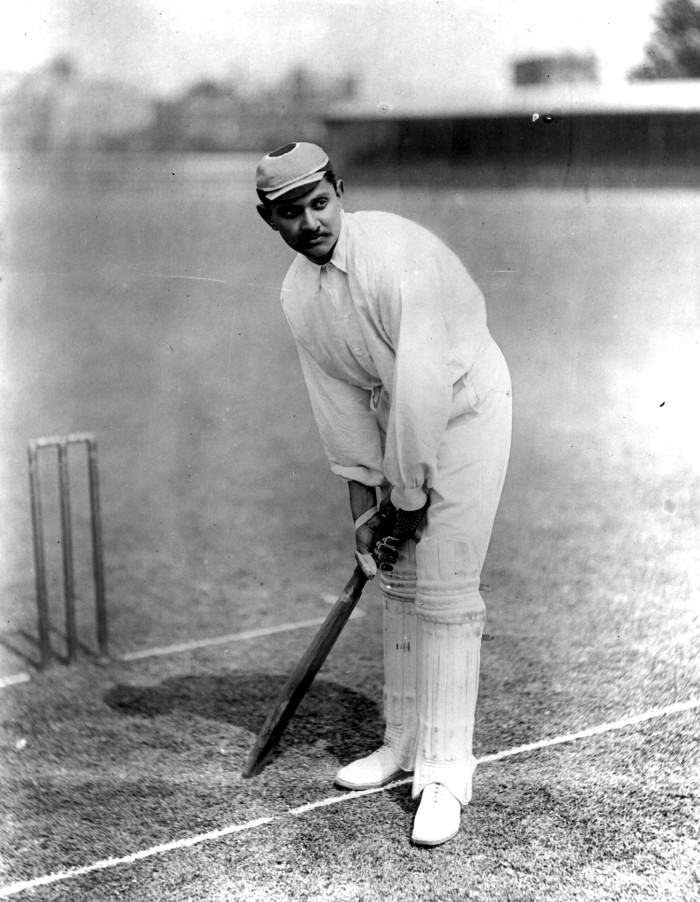

In purely sporting terms, Indians have contributed enormously to a game once regarded as quintessentially English. When, back in the 1890s, a batsman named KS Ranjitsinhji emerged as a star on the county circuit, a Yorkshire bowler remarked in disgust that this Indian “had never played a Christian stroke in his life”. Ranji’s wristy elegance was in marked contrast to staid English orthodoxy. Later Indian batsmen have likewise enriched the sport with their artistry. India has simultaneously produced a line of skilful spin bowlers, who rely on flight and variation rather than pace or strength.

The contributions of Indian cricket administrators, however, have been less salutary. In how it is organised and structured, the sport has inevitably partaken of the uglier aspects of Indian society, such as nepotism and majoritarianism.

The BCCI has a former cricketer, Bengaluru’s Roger Binny, as its president. Binny seems a pliant figurehead; the real power lies in the hands of the secretary, Jay Shah, the son of the second most powerful man in India, home minister Amit Shah. The BCCI appears effectively to be run by India’s ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata party. Other key office-bearers are the treasurer, Ashish Shelar, a BJP politician from Mumbai; and the IPL chair, Arun Dhumal, the brother of a serving minister in Narendra Modi’s cabinet. Like Jay Shah, they are seen by critics to have personal connections rather than administrative acumen. Given the enormous social prestige that cricket and cricketers command in India, the BJP hopes to consolidate its power and political influence through its control of the BCCI.

The founders of the Indian Republic refused to discriminate on the grounds of religion or language. The BJP, on the other hand, explicitly views India as a “Hindu” country. Senior cabinet ministers openly proclaim their desire to construct a theocratic state run for and by Hindus alone. Within social media the demonisation of Muslims is ubiquitous. This places a special burden on Muslim cricketers who play for the national team. If they perform well, they are seen as loyal citizens of this Hindu state-in-the-making; if they perform poorly, as agents in the pay of a foreign power (usually deemed to be Pakistan).

Indian cricket administration has become an instrument of the ruling party. A large number of Indian cricket fans wear their religious bigotry on their sleeves. Perhaps the most egregious example of the moral contamination of cricket, however, has been the naming of a major stadium after the current prime minister. This took place in the city of Ahmedabad, where Narendra Modi himself was based for many years, as the chief minister of the state of Gujarat.

The stadium previously carried the name of the celebrated nationalist stalwart Vallabhbhai Patel. In February 2021 it was renamed for Modi, in the presence of the home minister, Amit Shah, and in time for a Test against England. Two years later the prime minister visited the stadium during a Test against Australia, when he was presented with a framed photograph of himself by Jay Shah, the son of his closest political associate. Sadly, no Indian newspaper had the courage to print what would have been the most appropriate headline, viz: “Narendra Modi visits the Narendra Modi Stadium to accept a portrait of Narendra Modi.”

Cricket is popular everywhere in India. Yet prior to this renaming, Ahmedabad was never regarded as a major cricketing centre. Mumbai and Chennai have more honourable cricketing histories, and more engaged cricket followers. Even Bengaluru and Hyderabad have been more important to Indian cricket, player-wise and fan-wise. However, after the rise to national political dominance of Modi and Shah, they have ensured that the epicentre of Indian cricket has shifted to Ahmedabad. In recent years the final of the Indian Premier League has been played at the Narendra Modi Stadium; and so shall the final of the present World Cup.

The first match of the World Cup was also played at the Narendra Modi Stadium. It was between New Zealand and England, who had played a thrilling final in the last World Cup at Lord’s, the home side winning by the skin of their teeth. Now, in front of a scanty crowd in Ahmedabad, New Zealand won a resounding victory. The next match played at the Modi Stadium had a full house, because India was pitted against Pakistan. Back in 2011, the two teams had played one another in the semi-final, held in the Punjab town of Mohali. The Indian government issued some 6,500 visas to allow Pakistani fans to come and cheer for their team. For this match in Ahmedabad, however, the Modi regime refused to grant visas to Pakistani fans. Worse, the PA system played patriotic Indian songs; worse still, Pakistani players were taunted with shouts of Jai Shri Ram, a militant religious slogan that sometimes serves as a Hindu war cry.

This World Cup, although hosted by the BCCI, is technically organised by the International Cricket Council. In the past, the ICC has sought to ensure that fans of all nations were represented at its events. This time, it allowed the BJP-influenced BCCI to orchestrate an exhibition of hyper-nationalism at the Modi Stadium. As expected and desired, the home side won against Pakistan, mostly because they were the better team, although even some Indian fans were embarrassed at the atmosphere that enveloped the match.

As an Indian democrat I am, of course, dismayed by this cult of personality. As a cricket fan, I am distressed by it too. The BCCI’s subordination to this cult debases a game I have loved and followed all my life.

Many Indians share my sentiments. Many others don’t. They hail Modi as a redeemer, sent by God to finally rid India of the alien Muslim and Christian influences that have allegedly polluted it down the centuries. Of his dismantling of democratic institutions, of his regime’s assault on the press and on the universities, of the deepening religious polarisation and rampant environmental degradation under his watch, they seem not to care — or perhaps, as the old Stalinists once saw the Gulag and the persecution of peasants, merely regard them as the necessarily amoral means to achieve their fantasised Golden Age.

Next summer, India will hold its 18th general elections. Going into these polls, the prime minister and the ruling party already have enormous advantages over the opposition; far greater financial resources, a pliant media, and a compromised bureaucracy among them.

Nonetheless, leaving nothing to chance, they have planned three spectacular shows. The first was the G20 meeting hosted by India in September, when some, but alas by no means enough, attention was paid by the international press to the Modi regime’s attacks on minorities and political dissidents. The third will be the inauguration next January of a massive new temple to the Hindu god Rama, in further pursuit of the BJP’s majoritarian agenda. In between comes this Cricket World Cup, a stoking of nationalistic, and occasionally jingoistic, pride through the medium of what is not merely the favourite sport, but also the most alluring form of entertainment, for Indians today.

In the meantime, I have set aside my own political preferences by focusing on the cricket. The team I have myself most enjoyed watching are Afghanistan, absolute underdogs who were not expected to win a single match, but have so far won four. Powered by a quartet of spinners of contrasting styles — including the 18-year-old Noor Ahmad — the team from this war-ravaged and desperately poor nation have defeated England, Sri Lanka and Pakistan, all former World Cup champions. I also warm to South Africa and its admirably multiracial team, with players drawn from African, Indian and white backgrounds. One of the joys of watching them play is to see their captain, the inspirational Temba Bavuma, offer advice to his strike bowler, Marco Jansen, who towers a foot-and-a-half above him.

In this World Cup, Australia and New Zealand have also had their moments. However, the standout performance has come from the home team, who are at the time of writing the only unbeaten side in the tournament. Among the stars of the Indian 11 are the brilliant batsmen Rohit Sharma and Virat Kohli, the superb swing bowler Jasprit Bumrah, and the gifted spin-bowling all-rounder Ravindra Jadeja.

Sharma, Kohli, Bumrah and Jadeja would all walk into any World XI. The national team they adorn are favourites to win this year’s World Cup. Were that to happen, many Indians will be quick to seize on that as further proof of the visionary leadership of Narendra Modi, and of our impending global dominance in spheres other than cricket as well.

I would rather see it in its place; as a triumph of 11 cricketers on a cricket field, with little bearing on the economic, political, or indeed moral standing of the country whose passports these cricketers happen to carry.

Ramachandra Guha’s books include ‘India after Gandhi’ and ‘The Commonwealth of Cricket’. He lives in Bengaluru

Follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen