Given that he is a French ex-professional skier, son of a celebrated climber and co-founder of the hottest brand in the mountains, you might expect an interview with Camille Jaccoux to take place in a snow-covered chalet in one of the deep-powder meccas where his products are so lionised — probably Chamonix, perhaps Engelberg, Alta or Revelstoke. In fact, I find myself walking along a traffic-clogged road in Battersea, south-west London, passing barber shops and off-licences before turning off to find Jaccoux’s house in a Victorian terrace.

“I’ve always needed both mountain and city,” he explains as we take a seat in his lounge. Dressed all in black, he sits on a black leather sofa against a wall covered in a geometric black-and-white print that makes my eyes swim. There is one pair of skis in a corner but otherwise no mountain paraphernalia — rather than ski magazines, the shelves have books on Francis Bacon, Andreas Gursky and Isabella Blow.

“When I wasn’t skiing, I was interested in culture, music, design, and so I wanted to be in the city.” For many years that meant Paris, but after meeting and marrying London-based creative director Mai Ikuzawa, he has spent much of the past decade living between Battersea and Chamonix, a dual perspective that might go some way to explaining his brand’s success where so many other ski start-ups have foundered.

Black Crows only released its first ski in December 2006 and its first outerwear in 2015, yet it seems to have leapfrogged the big, decades-old ski brands in terms of desirability. Jaccoux won’t give sales figures but says the privately owned company is growing consistently by 20 per cent annually. It now achieves 40 per cent of sales in the US, a market that small European ski brands have previously struggled to break into.

“They’ve managed to acquire a really strong cult following,” says Henry John, information and advice manager at the Ski Club of Great Britain. “The skis are bright and fun — they stand out on a rack like pretty much nothing else, something that really differentiates them from the big legacy ski makers — plus they ski really well too.”

Where traditional ski brands have always focused on the buttoned-up world of downhill and slalom racing, emphasising the technology and aesthetics trickling down from the World Cup circuit, Black Crows comes from the more countercultural world of freeriding (or, in pre-millennial terms, off-piste skiing). Rather than carry jargon about performance and innovation (Elan’s “Powermatch technology”, Head’s “Kinetic Energy Recovery System”), Black Crows skis feature jokey slogans hidden on the sidewalls: “I’m not scared”; “I don’t remember it being this far”; “You said you’d call”; “Still on mute”.

It all started conventionally enough, if slightly by accident. Jaccoux was a former mogul skier who had been in the French ski team but turned to freeriding in the late 1990s after narrowly missing out on the Nagano Olympics. He became friends and Chamonix flatmates with Bruno Compagnet, a dreadlocked hero of freeride competitions originally from the French Pyrenees. “But the idea of starting a ski brand never even crossed my mind,” says Jaccoux, now 49.

Instead he worked as a professional skier, sponsored by Salomon, appearing in movies and adverts (once being hired as a stunt double for James Bond). Later he branched out into creating his own content, working as a photographer and founding a magazine, WeSki, to celebrate the “rebirth” of skiing in the mid-noughties, as the invention of fat powder skis, radical sidecuts for carving and a boom in freestyle helped reinvigorate the sport.

A chance meeting changed his career. On a foggy day in 2004 at Chamonix’s Grand Montets ski area, Jaccoux got chatting in the cable car with one of the few other skiers braving the bad weather. He turned out to be Christophe Villemin, an industrialist and investor (now an operating partner at Searchlight Capital and chief executive of Midi Management). Villemin admired Jaccoux’s 205cm prototype Salomon skis, and the pair swapped numbers. When they later met for dinner, along with Compagnet, conversation turned to which ski they would buy if they were in a shop the following day. “In fact, none of us had an immediate answer. It was ‘I’m not really sure — I like these new brands, mostly from America, but . . . ’”

Encouraged by Villemin, Jaccoux and Compagnet began to investigate creating their own ski, one ideal for the steep and deep faces of the Grands Montets — “a ski that would go fast, float, perform well but also be playful. There was no computer, it was designed on a piece of paper,” Jaccoux recalls. They pressed 350 pairs of the Corvus, which immediately sold out.

More important than that ski’s characteristics, though, was the creation of a brand. The name comes from the choughs that congregate around Alpine crags, according to Chamonix legend the reincarnated souls of mountain guides. “There are stories about the birds in many civilisations, they live together as a group, and there was also this American rock band, so we said ‘That’s cool.’”

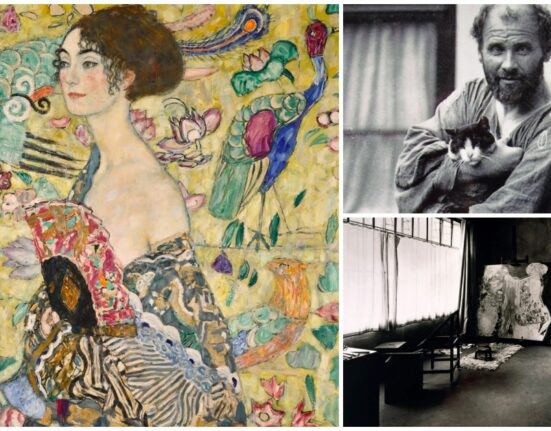

For the design, Jaccoux reached far beyond the ski world to designer Yorgo Tloupas, a friend who was art director and co-founder of the London-based cars and fashion magazine Intersection. (Tloupas would go on to create designs for companies including Artcurial, the Paris auction house, the drinks maker Ricard and many more — and also to introduce Jaccoux to his wife Mai.) “A couple of months later he called me and said he had something,” says Jaccoux. “When a kid draws a bird, they do a V. And you don’t want to ski alone, you want to be in a group. He told me with three or six of these Vs we can do a geometric chevron, and with this chevron we can do unlimited patterns, any product we choose.”

That simple idea has been rigorously applied to every Black Crows product ever since — from chevron-patterned water bottles to down jackets with V-shaped baffles — giving the company an instantly recognisable and completely distinct look. Where the skis have bright colours, the clothing typically uses single, often muted, tones, an elegant alternative to more garish rivals.

If the meeting with Villemin was luck, more good fortune followed. In 2008, the US brand Armada released a revolutionary ski called the JJ, designed by Julien Regnier and the late JP Auclair, which showed the possibilities of emerging technologies such as rocker and reverse camber. Yet rather than build on its success, Armada fired Regnier, allowing Jaccoux, who had known him since they were on ski teams together as teenagers, to bring him to Black Crows in 2010.

The recent boom in ski-touring, supercharged by the Covid pandemic when lifts were closed and interest in fitness and the outdoors blossomed, has given another boost.

It is easy to see parallels with the cycling brand Rapha, a start-up that created a new aesthetic in the noughties before being sold for £200mn in 2017. But Rapha’s success, and high prices, were already creating a backlash — it was becoming seen as a brand for city boys rather than “real” cyclists. Can Black Crows, now sold alongside Moncler and Bogner by online fashion retailer Mr Porter, maintain its countercultural cool?

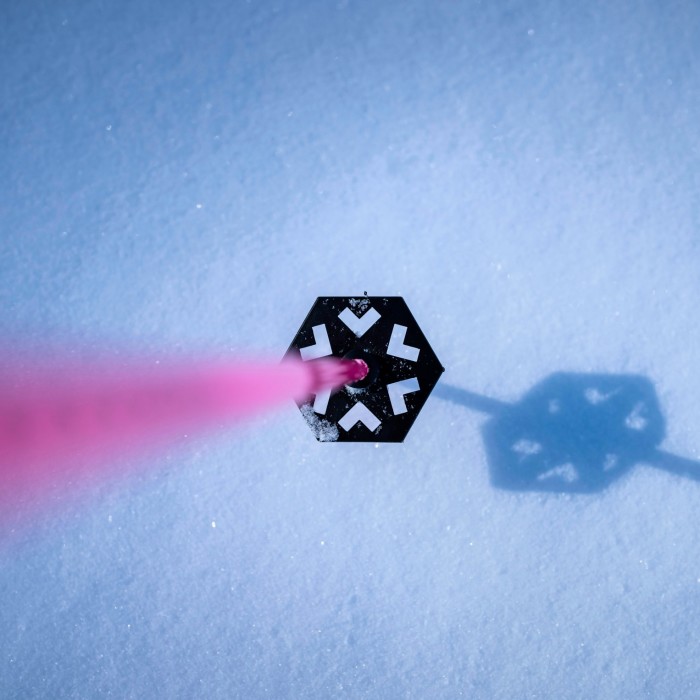

Jaccoux hopes that focusing on what he calls “ski culture” will allow it to keep a sense of authenticity. So there are “ski sauvage” events in resorts across the Alps, where the public can try out Black Crows products and ski with staff and sponsored athletes, as well as a four-day electronic music festival in Chamonix. The online brand presence is a world away from conventional advertising, instead emphasising short films with strong stories, the products featuring only incidentally. In one film, a group of ski tourers travel around Svalbard by sailing boat; in another, they explore derelict resorts in the Alps.

“If you say you’re a surfer, people imagine the guy with the van, travelling the world,” says Jaccoux. “If you say you’re a skier, they just think you’ve got a job as a ski instructor, but there’s a whole lifestyle around it.”

Black Crows currently employs 55 people — its skis are made in other manufacturers’ European factories. The next objectives include launching its own retail stores in key cities and ski resorts and developing new, more experimental skis that build on the success of the unorthodox Mirus Cor, which blends carving and freestyle capabilities.

For Jaccoux, the future is more Chamonix than Battersea. His two kids have reached an age where they can no longer swap between schools, so the family is settling more permanently in France. “I’ll keep coming back here for inspiration, though. London is still a good city, even after Brexit.”

Follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen