Two days after news broke Fr. Marko Rupnik was incardinated by Slovenia’s Koper diocese, the Vatican announced Oct. 27 that Pope Francis has lifted the statute of limitations on abuse accusations against Rupnik to allow for a formal investigation of the case by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Even as that process begins, victims’ advocates are expressing dismay at the fact that Rupnik was readmitted to a diocese in the first place, and debate continues over whether his artwork should be withdrawn from churches worldwide.

“How distressing this must be for the religious sisters who were his victims. I hope the diocese and bishop concerned are also offering them psychological care,” said Antonia Sobocki, director of the British-based LOUDFence organization.

“People are so tired of seeing the church and its moral authority sacrificed on the altar of the careers of such clerics. They can’t understand why he isn’t being made to answer for what he’s done,” she said.

Slovenia’s Koper diocese incardinated the mosaic artist four months after he was expelled from the Society of Jesus amid multiple accusations of sexual misconduct.

Meanwhile, a leading former abuse victim said he also failed to understand why Rupnik had been “justly dismissed by the church, but then allowed back.”

“He isn’t the only artist who’s successfully made a huge business out of his work,” Daniel Pittet, a Swiss university librarian and Catholic deacon, told OSV News.

“However famous he may be, he can rightly be forgiven only by his victims. But it seems he has plenty of influence,” Pittet said. As an altar boy, Pittet was a victim of abuse, including repeated rape by Swiss friar, which he described in a book Father, I Forgive You.

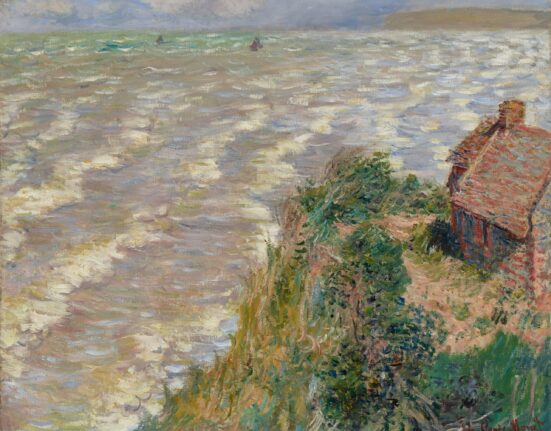

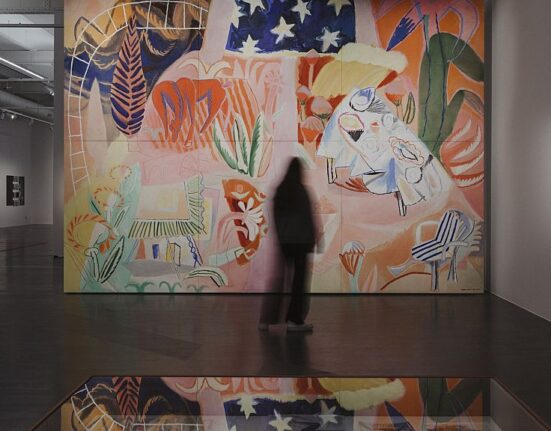

Born at Zadlog in western Slovenia, Rupnik was ordained in 1985 and became famous for his large-scale mosaics, which are displayed at over 200 Catholic centers worldwide, including the Vatican’s Redemptoris Mater Chapel and the St. John Paul II National Shrine in Washington D.C.

In December 2022, Rome’s Jesuit Curia disclosed the priest had been suspended after multiple claims of sexual and psychological abuse were made, but added that the case had been dismissed by the Vatican’s Dicastery for Doctrine of the Faith because of the church’s 20-year limitations statute.

It also revealed that Rupnik had been briefly automatically excommunicated in January 2020 for absolving a woman at confession after having sex with her, but said the order had been rescinded when he repented of the crime in May 2020.

In June, the Jesuit order said it had compiled a 150-page dossier of “very highly credible” accusations against Rupnik, believed to involve dozens of women, and had now expelled him for “stubborn refusal to observe the vow of obedience.” The Jesuits had exhorted Rupnik to atone for his misconduct and enter into a process of reparation with his victims, but he refused, as reported by The Associated Press.

However, in a Sept. 18 report, the Vicariate of Rome said a canonical visitation at Rupnik’s Centro Aletti for spiritual arts, where abuses were reported, had highlighted “gravely anomalous procedures” used against the priest.

It added that the visitation, ordered by Cardinal Angelo De Donatis, had concluded the center led “a healthy community life.”

In a Sept. 19 open letter to the pope and other church leaders, five former victims of the priest from Slovenia’s Loyola Community said the Vicariate report showed claims of “zero tolerance” were “just a marketing campaign,” adding that its “ostentatious hubris” had ridiculed “the pain of victims.”

However, in its Oct. 25 statement, the Koper diocese confirmed that Rupnik had been accepted by Bishop Jurij Bizjak at the end of August and should be “presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law,” adding that he would now enjoy “all the rights and duties of a diocesan priest.”

In Great Britain, where Rupnik’s artwork is widely displayed, Bishop Stephen Wright of Hexham and Newcastle declined to comment on “decisions made in other dioceses,” but told OSV News Oct. 26 he had resolved not to use the priest’s mosaic imagery.

However, Sobocki, the victims’ advocate, said other dioceses remained “hesitant” about scrapping Rupnik’s artwork, instead believing a “gentle diplomatic approach” was preferable to “imposed decisions.”

“The Catholic Church isn’t short of beautiful artworks — it shouldn’t have to choose between beauty and morality,” Sobocki told OSV News.

“But while bishops here are seeking to remove him, others seem to be lobbying the pope and Vatican to rehabilitate him at the expense of the church’s moral credibility,” she said.

Attitudes to Rupnik’s art vary widely. At Fatima in Portugal, art historian Vitor Serrão cited the priest’s work Sept. 13 as an argument for making the Marian sanctuary a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

However, in Brazil, where the priest’s November 2022 honorary Catholic university doctorate has been revoked, the pilgrim center of Aparecida confirmed in August that it was canceling a 2019 order for 110 biblical mosaics.

“The Catholic Church isn’t short of beautiful artworks — it shouldn’t have to choose between beauty and morality.”

— Antonia Sobocki

A spokeswoman for the French Marian sanctuary of Lourdes, where the priest’s mosaics feature prominently at a Rosary Basilica, told OSV News that Bishop Jean-Marc Micas of Tarbes and Lourdes had set a commission after “queries and complaints” to decide on the artwork’s future.

In Poland, the press officer at the St. John Paul II sanctuary in Krakow, where Rupnik led spiritual meditations in November 2022, told OSV News abuse victims had agreed to relocate their prayer meetings from the site’s main basilica so as not to be disturbed by his mosaics.

In his interview, Daniel Pittet said he had no doubt about Rupnik’s “many horrible personal faults,” but added that many great church artists had also been “twisted and dishonest people.”

“Throughout history, there’ve been people at the church’s very center, even popes, who’ve done stupid, terrible things. If we now rush in to filter and annul their work, we could end up emptying our churches,” Pittet said.

However, this was rejected by Sobocki, who said she believed Rupnik’s artwork contains visible hints of his crimes, adding that “deviant artists” from history had no living relatives who could be “shocked and traumatized” by seeing their work.

“Perhaps a museum could be opened for those who enjoy looking at macabre rape art — but it doesn’t belong in a sanctuary and shouldn’t bar people from practising their faith,” the British advocate told OSV News.

“Some of the religious sisters who fell victim to Rupnik still aren’t even able to access the sacrament of reconciliation. The idea of having artwork by a man capable of such things around a tabernacle is about as insulting and sacrilegious as you can get,” Sobocki said.

Pope Francis has not met the alleged victims of Rupnik, although a Sept. 27 statement by the Vatican said that “The Pope is firmly convinced that if there is one thing the Church must learn from the Synod it is to listen attentively and compassionately to those who are suffering, especially those who feel marginalized from the Church.”

On Sept. 15 however, the pope met with theologian Maria Campatelli, a close collaborator of Rupnik.

In June, Campatelli published a letter defending the artist against “a media campaign based on defamatory and unproven accusations.”

Slovenia’s Catholic weekly, Družina, said Oct. 25 that Bizjak had agreed to admit Rupnik to his diocese “on an experimental basis” after consulting De Donatis and the Vatican’s Ljubljana-based nuncio, Archbishop Jean-Marie Speich.

The paper added that Rupnik could now continue “conducting spiritual exercises and creating mosaics,” but was likely to remain a resident of Rome rather than Slovenia.

The Vatican statement on Oct. 27 did not state what limitations would be imposed on Rupnik now that the statute of limitations has been lifted and the investigation will be reopened.

The Pontifical Commission for Protection of Minors has approached known victims of Rupnik, asking to meet and hear about their treatment by the church.

However, a former Loyola Community sister, Mirjam Kovac, now teaching canon law at Rome’s Pontifical Gregorian University, where the priest received his doctorate in missiology, told OSV News Oct. 26 she believed the September open letter of alleged victims and related media interviews had been enough to foster “understanding of the case.”

“At the moment, it’s time for me to understand and elaborate my personal story in silence and dialogue with other community ex-sisters,” Kovac said. “Only later will I be ready to make my thoughts public,” she said.