The people in the waves, with their somnambulant charm. Sunlight follows the ocean. You made fun of your power, Mount Fuji dwarfed by your nature. The fishermen are dying, they look prettier now. You sing and sing and sing.

The Seattle Art Museum has a temporary exhibit displaying artwork by Japanese painter, Katsushika Hokusai, and other artists that were greatly influenced by his style.

Hokusai and his “Under the Wave” ca. 1830-31 (the Great Wave), were produced during the end of the Edo period, during Japan’s self-isolation. Away from external colonial or religious influence, Japan had seen any number of artisans picture their historic utopia, any number of landscapes depicting Japanese life. While the rest of the world grew into industrialization, Japan had cut itself from the thieves and international merchants, from Europe and the U.S. since 1639, and stayed brilliantly mysterious for more than 200 years.

Along the rivers and beside the flesh, merchants paraded their markets in search of sensual pleasures. As their ranks advanced following Japan’s booming economy, they were able to afford commodities previously seen as luxury. Education, travel, books and art were purchased in the new Ukiyo, in the “floating,” transient world.

Commercial prints and woodblocks were sold by the thousand. Landscapes of the new world, sex and celebrity portraits collected like playing cards and mass production had been highly profitable. The arts, in Japan, flourished.

Hokusai, in his teenage years, had mustered, already, so much popularity, painting portraits of Kabuki actors for woodblock prints. As his subject matter transitioned to landscape in his later life, Hokusai’s artistry became an obsession, painting sceneries and everydayness with a sort of serendipity.

“All I have done before the age of seventy is not worth bothering with,” Hokusai is quoted as saying of his life’s work.

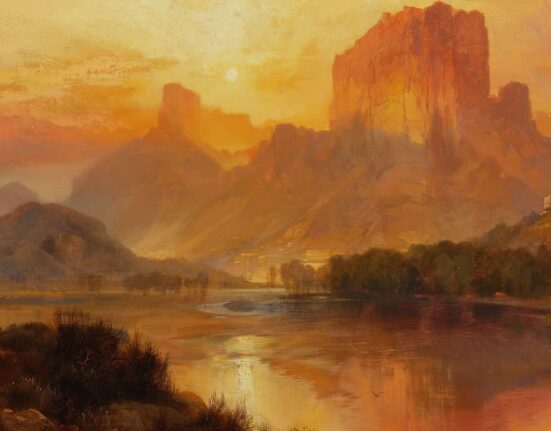

In his most ambitious project, “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji,” Hokusai revealed Japan’s Mount Fuji from the forest, the village, the lake, the river, the beach and the sea. The Great Wave, with its Prussian blues and fine lines, pivoted Japanese artistry and continued international interest.

I traveled to the Simonyi special exhibition gallery, into the Seattle Arts Museum, to realize Hokusai’s influence on his contemporaries and question why his paintings hold such magnetism.

I was surprised by the popularity, by how many people had come alone to view the art there.

Paintings of blue and green, copying, so easily, the sky, the earth, the dancers floating on the tops of the sea. The sea’s coolness and drama, the excellence of the sea.

Adam Ganc, a fellow onlooker of the exhibit, towering over Hokusai’s collection, told me it was “curiosity” and his love for the European art period called Art Nouveau that had brought him to the exhibition.

“You can see his influences in so much current art,” he said. “I can see some of the influences throughout time, and getting these designs in my mind gives me a lot of pleasure.”

Ganc knows that Hokusai is typically successful at conveying subtle messages within his art, with incredible craftsmanship to accompany it. Tee Sae, perusing the art on a quiet day, was impressed with the same intrigue and told me she’s always been captivated by it.

“I’ve seen it for years and wondered why it was so interesting to me and everyone else here, why it’s been timeless, why they’ve built this whole exhibit around it,” Sae said.

Sae was staring at Hokusai’s “Li Bai Admiring a Waterfall” ca. 1849. In it, the Chinese poet, Li Bai, is entranced by the falling water, almost human-like. The sky above the water, a planet of waves.

Hokusai’s collection had been dizzying and gratifying. Mimics of the Great Wave marched around in pale yellows and exotic blues, art that made you feel its force and beauty and greatness.

As I left the exhibition, I spoke with an older couple I’d noticed upstairs. They were smiling as I approached them, as I asked why the Great Wave had lured in so many people. They told me their names, K and John Robinson, and the woman laughed and looked to her husband.

“It grabs at the imagination,” Robinson said. “The wave and the views of Mount Fuji are forever, they don’t change. It’s nature.”

The terror of the wave in Hokusai’s collection, and other works from the series of thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, can be viewed at the Seattle Arts Museum until Jan. 21. Full of imagination and fright, the pilgrimage into a world off Kanagawa is easy.