Henri Matisse picked up the telephone and dialled the number of the nursing agency. He knew it by heart. It was the late summer of 1941 and the 72-year-old had been effectively bedridden for six months after enduring a major operation to treat duodenal cancer.

It was not a happy period. The painful aftermath of the procedure had left him largely unable to paint. His wife, Amélie, whom he had married in 1898, had walked out in 1939 after discovering one marital infidelity too many, while in the wake of the Nazi occupation he had passed up the opportunity to leave France for South America, declaring: “It felt to me as if I would be deserting. If everyone who has any value leaves France, then what remains of France?”

Stranded at home in Nice, he found himself relying upon his housekeeper and secretary Lydia Delectorskaya by day, and an agency nurse on hand at night. His regular nurse had just given her notice, so the artist called the agency to discuss her replacement.

“Send me someone young and pretty,” he instructed at the end of the call.

A few days later, 21-year-old Monique Bourgeois arrived at his door. As she began busying herself around the elderly artist, arranging his pillows and ensuring his medication was in order, neither Bourgeois nor Matisse could have suspected they were about to embark on the most significant relationship of their lives. Bourgeois was effectively at the beginning of hers, the artist in the twilight years of his, but both would be enervated and changed by the time they would spend together.

Born into a family of cloth weavers in the north-east of France, Matisse had given up his law studies as a young man to study painting under the symbolist Gustave Moreau. Having shown enough promise to be featured in Paris salons, it was only in his late 20s that Matisse discovered how the bright colours and light of the south of France could inspire the vivid works of dramatic, colourful panache that would define his style.

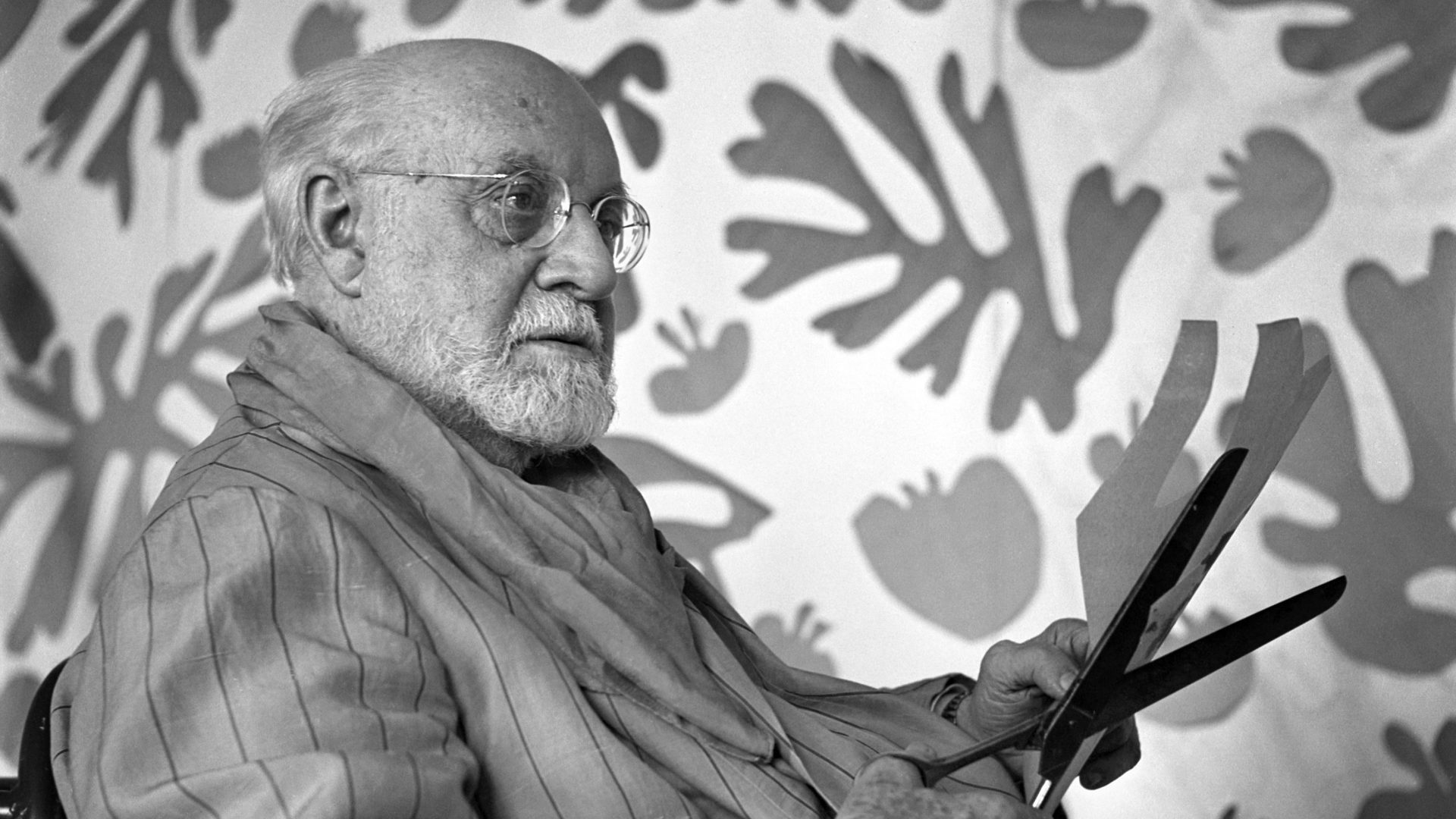

Alongside artists like André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, Matisse became a leading light in the Fauvist movement, derived from the French word for “wild beasts”. The basic principles of this period were maintained through his abstract works of the 1910s through the sunlit splashes of what was known as his Nice period, beginning in the 1920s and his final years revitalised by his friendship with a young nurse who materialised at his door as the sun set one late summer afternoon under the gloom of occupation.

Despite the half-century between them, the pair developed a remarkable bond. Bourgeois came from a military family uprooted from their Metz home by the invasion. Her soldier father died of wounds soon afterwards and, finding herself in an unfamiliar place with a sick mother to support, not to mention her own tuberculosis, when Bourgeois received the call to attend to the elderly artist it was the first positive thing to happen to her in months.

“I was comfortable with him,” she recalled years later. “I could breathe, I could relax. It was a haven of peace.”

Low on confidence thanks to an upbringing in which she was told constantly she was ugly and useless – she had never worn makeup and never read a book without first securing her mother’s permission – Bourgeois triggered something protective in the old artist.

“Who said you were ugly?” he demanded. “Your parents? What I see is overall volume, expressiveness, a forehead like a tower, the splendid mass of your hair, the oval of your face, the expressive gaze. It is the feeling of being alive. There is nothing cold about you.”

For his part, Matisse found Bourgeois utterly refreshing. She showed no signs of being impressed by him – when he asked what she thought of his work she told him, “Monsieur, I like the colours a lot but the drawings… not so much” – yet still inspired him to new artistic heights as both muse and model.

“It was Monique, more than any other model, who renewed his determination to push forward once again as a painter into unknown territory,” said Delectorskaya.

After a few months, Matisse had recovered enough to no longer need the services of a nurse, by which time Bourgeois was ready to fulfil her ambition to take holy orders. Before they parted ways the artist persuaded her to sit for the first of a small series of portraits in oil, Monique in Grey Robe.

“It didn’t look like me, I didn’t think it was very good,” she recalled.

Matisse, never a religious man, tried to dissuade her from her calling but by the time the pair met again in 1946 in the small town of Vence, to where Matisse had been evacuated at the end of the war, Monique Bourgeois had become Sister Jacques-Marie.

When he learned from her that the Dominican convent where she was recovering from her tuberculosis was reduced to using a damp garage as a chapel, Matisse summoned all his influence to help renovate the building while dedicating himself to its interior design.

Criticism arrived from all sides. Picasso, with whom he enjoyed and endured a long love-hate relationship, was astounded. “Why not a market?” he asked. “At least then you could paint fruit and vegetables.” The Catholic Church, meanwhile, was unsure about entrusting such an important undertaking to a secular artist renowned for painting nudes.

For the entire four years of the project Sister Jacques-Marie found herself in the difficult position of go-between. For Matisse, however, the project became an obsession.

Jacques-Marie built a plywood model of the building on which he could project his ideas for interior decoration, stained-glass windows and even the vestments to be worn by the priest, and while he insisted all credit for the project be shared equally with Jacques-Marie, when she informed him of her conviction he was being inspired by God he told her, “yes, but that God is me”.

The Chapel of the Rosary at Vence was completed in 1951, three years before the artist’s death.

“The result of my entire working life,” Matisse called it, adding, “despite all its imperfections I consider this to be my masterpiece”.

Sister Jacques-Marie outlived Matisse by a little over half a century, years she spent politely fielding questions and deflecting the occasional insinuation about the nature of their relationship.

“I never really noticed whether he was in love with me,” she told Paris Match in 1992. “I was a little like his granddaughter or his muse. He was always a perfect gentleman.”