The artist Betye Saar lives less than two miles from the bars, billboards, and bustle of Los Angeles’s Sunset Boulevard, but her home, in Laurel Canyon, seems far removed from Sunset’s gleaming capitalism and packaged sex. Saar’s studio and house, where she has lived for more than sixty years—she is now ninety-seven—are dedicated to history, especially American history as it relates to Black women. In her work, that history is often told through pop-culture artifacts, which, in Saar’s hands, take on a witty poetic resonance—an aura—that they wouldn’t otherwise have. Just as Jasper Johns used the flag and beer cans to critique our ideas of the sacred and the disposable, Saar uses objects to address the power of the image in America. But her America is to the left of Johns’s largely male-oriented world. Her layered assemblages, which sometimes resemble the interior of a hope chest, are also filled with inquiry: into the nature of mythology, and specifically how and why we mythologize the Black woman.

Saar uses prefabricated pieces (Black dolls, Aunt Jemima paraphernalia, advertising images, and the like) to show us how women of color have been repeatedly treated as props—accommodating, beneficent characters—in the never-ending drama of race. These images rarely even hint at an interior life, but Saar makes that interiority manifest. Her seminal work, “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” (1972)—which the activist Angela Davis reportedly credited with sparking the Black women’s movement—is a box containing a smiling Mammy figure with a gun under each arm, ready to blow all those stereotypes away. In the installation work “A Loss of Innocence” (1998), Saar suspends a long white cotton and lace dress from a hanger above a child-size wooden chair; to the bottom of the gown she has attached labels with words such as “Pickaninny,” “Tar Baby,” and “Coon Baby”—epithets that not only besmirch innocence but remove the very possibility of it. What are children of color left with? The sense that no one, not even a loving parent, can protect them from a world of hate. Saar’s white dress, which looks homemade, brings to mind another frequent theme: women’s labor as a locus of creative ingenuity. Washtubs, jewelry boxes, sewing materials, buttons, and ribbons all appear in her art: she wants us to see how the world is constructed by the hands of invisible women who make it work.

Alison, Betye, Tracye, and Lezley Saar, in 1965, at the Renaissance Pleasure Faire, at the Paramount Ranch in Agoura Hills, California.Photograph by Richard Saar / Courtesy the artist / Roberts Projects

Behind a pink door in Saar’s house, above her studio, is a small kitchen; opposite the stove and the counter, she has fashioned a sitting area. The space is snug; the windows look out onto the trees and foliage of Laurel Canyon. You have the sense of gazing down from the deck of a great ship. In both the kitchen and the sitting area there are ceramic Aunt Jemima-like figures, cloth dolls in brightly colored skirts, clocks, and any number of other elements that you might see in a Betye Saar assemblage. The artist herself—dressed, on the afternoon that I saw her, in February, in loose gray pants, a gray T-shirt, and an oversized plaid shirt—is small, too, but age has done little to diminish the magnitude of thought and feeling in her eyes when she speaks, in a voice that is light, youthful, and mischievous.

Saar moved to this house in 1962 with her then husband, the ceramicist Richard Saar—they divorced in 1970, but remained close until his death, in 2004. (“Are you married?” she asked me. “It’s a job.”) Laurel Canyon was “a hippie place” then, according to Saar, one where an interracial couple—Richard was white—and their three daughters, Lezley, Alison, and Tracye, were unlikely to be hassled. Frank Zappa lived nearby, and the Canyon was still fairly rustic. It was a place where Saar, who had grown up not knowing that a Black woman could be an artist, began to find her creative footing. The energy of second-wave feminism and the rush of Black nationalist politics helped.

Saar believes in the importance of the psychic world not only in art but in life, because she has lived in it. Born in Los Angeles in 1926, she was the eldest child of Jefferson Maze Brown and Beatrice Lillian Parson, who moved to California, from Louisiana and Missouri, respectively, to study at U.C.L.A. Both parents had great respect for education, and pushed Saar and her two younger siblings to embrace its possibilities. But even as a little girl Saar had another life that was separate from the family’s, one that she has tried to make visible in her work. “As a child, I was clairvoyant,” she told me. “I remember living in a particular house. I was maybe four years old, and would play in the carriage house in the back yard. There I imagined a friend named Rosie, who was always telling me stories. I’d come into the house and say, ‘Rosie says that Dad’s going to be late from work today because he missed his bus.’ And then my dad would come in later. He’d say, ‘Oh, honey, I missed the bus.’ And my mother would say, ‘Oh, yeah, Betye told us that.’ ” Shortly after Saar turned five, her father died of an infection, and Rosie died with him. Still, Saar’s early experience—and her parents’ support—gave her the assurance to trust her vision and her imagination.

After Brown’s death, the family lived first with his mother in Watts and then in Pasadena, where Beatrice supported her children by working at a department store and as a seamstress. Saar, a child of the Depression, also sewed from a young age, and made trinkets that she sold to her playmates and their families. After high school, Saar wanted to study art, but art schools at that time were largely segregated. “The Chouinard Art Institute was available to me, but it was private,” Saar wrote in a 2016 essay in Frieze. “And that was just one of the things black people didn’t go into—they didn’t study to be artists.” Fine art was for white people who came from a different class—one in which art could be a vocation. If you were Black, you had to find a job, some stability in an unstable world. Saar’s stepfather—her mother remarried when she was eleven—asked her, “Now, what are you studying art for? How are you going to make any money like that?” Saar told me. “And I said, ‘I suppose there are designers. They design cars. They design clothes. I can just be a designer.’ ” So Saar took design-related classes at Pasadena City College for two years, before transferring to U.C.L.A., thanks to an organization that raised money to pay tuition for minority students. There, she studied applied arts. “I didn’t take fine-art classes,” she said. “In fact, I think I was afraid of painting—thinking, You really have to be an artist to paint.”

After graduating, in 1949, Saar found employment as a social worker. The poverty and desperation she witnessed left a mark on her consciousness. Her face still fills with compassionate sadness when she remembers that job. “To have no resources, to be a woman with no resources . . . ,” she said, then fell silent. Around the same time, she and her friend the jewelry designer and painter Curtis Tann launched a small business, Brown and Tann, selling enamel jewelry, bowls, and plates that they had designed. Tann introduced her to other Black artists, including Charles White, who believed that Black art could be as much about racial uplift as it was about the artist’s aesthetics.

The lessons Saar had learned from her parents about the importance of education and work—who were you if you weren’t striving?—kept her on the move. In 1958, she began graduate studies at California State University, Long Beach, where she discovered printmaking. She was on campus one day when she smelled something strange. It was ink: “I wandered into the printmaking studio, and they were making all these things, and putting them in the presses and all. I said, ‘I want to learn to do that.’ ” To hear Saar describe the technical aspects of printmaking—“I had so much fun doing something which is called a ‘soft ground’; that’s putting an oily substance, like a grease, on a piece of metal, and drawing through to the metal. Then you put it in the acid. The grease resists the acid”—is to witness an enthusiast who believes in the joyful how of making the imagination visible.

“What can you do?” she said. We were sitting at her kitchen table, talking about how the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968, had prompted a more political voice in her work. “You’re a young mother—you can’t go to marches. You have to stay home and take care of your kids. You could contribute. I didn’t have a lot of money. So, what could I do to express that?” Her answer was her art. By then, all of Saar’s skills—as a printmaker, a designer, and a seamstress—had coalesced, in part because she’d found another artist whose vocabulary made sense to her. In early 1967, she visited the Pasadena Art Museum and discovered an exhibition of work by the brilliant assemblage artist Joseph Cornell. Saar was exhilarated by the worlds that Cornell created in boxes: unapologetically romantic and history-rich cosmoses, where dreams and cultural artifacts and even the stars Cornell loved, ranging from Lauren Bacall to Susan Sontag, were presented as though on a stage. The boxes, filled with images torn from magazines, old postcards evocative of a cultured Europe, fragments from old manuscripts, dolls, taxidermy birds, and so on, had a galvanizing effect on Saar. She soon began collecting materials to make assemblages of her own.

One of the things Saar found touching about Cornell was that some of his works were made to amuse his brother, Robert, who had cerebral palsy. Saar wanted her art to have a “healing effect,” too. I asked if she wanted to redeem people with her work. “Yeah. But not to preach, not to control. To give them a hint that there’s something else. There’s always other. And if you open yourself up to other, you can do and think all sorts of things.”

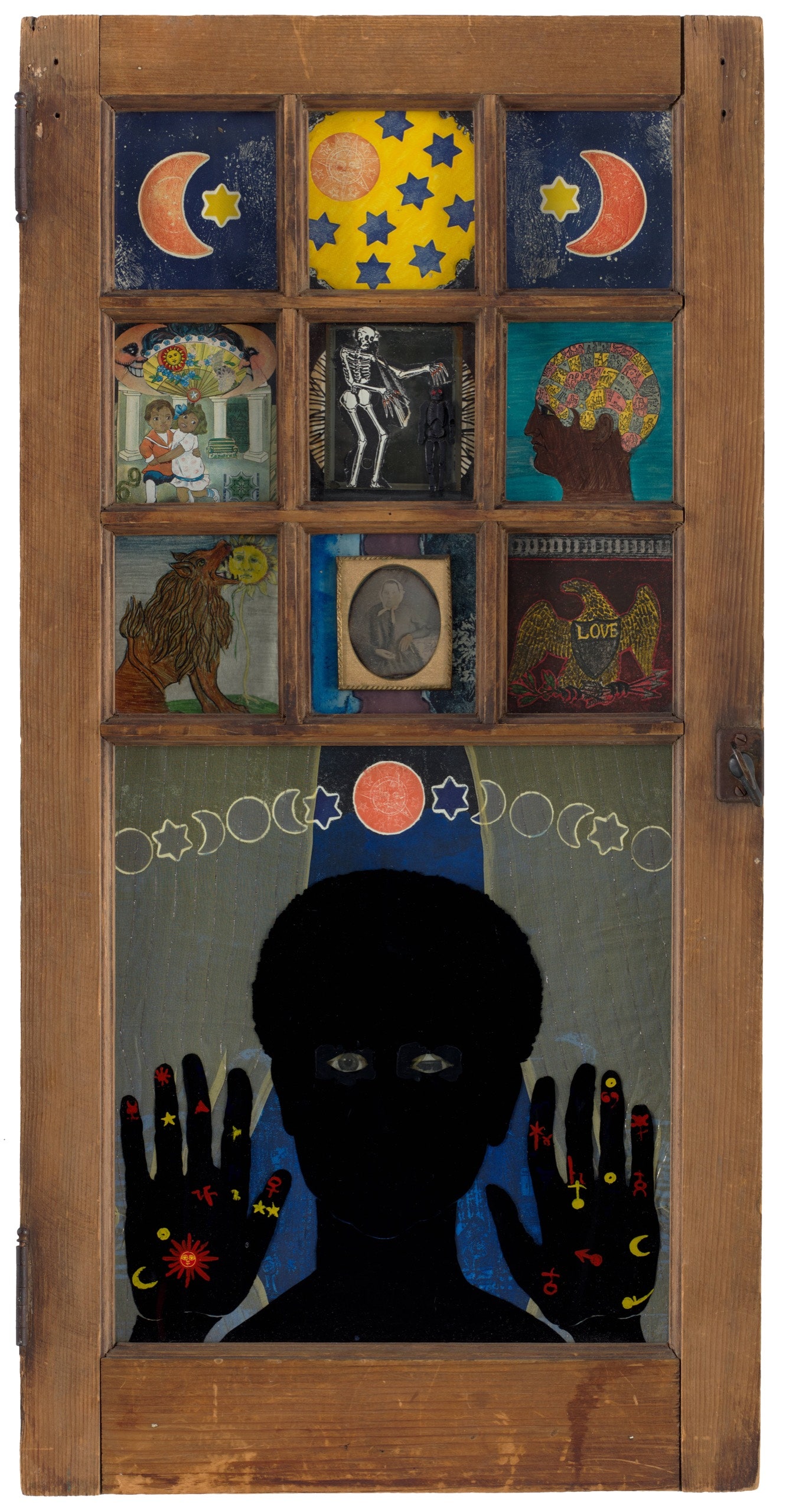

Among the first significant pieces Saar made was “Black Girl’s Window” (1969). A deeply personal work, it is a mixed-media assemblage that, like a Cornell, is contained in a wooden box—its “frame.” In it there are nine small panels, or windows, above a larger one. Two contain a quarter moon; another, an array of sun and stars. There’s a skeleton, a roaring lion—Saar is a Leo—and a daguerreotype of a white woman, a reference to Saar’s maternal grandmother, who was Irish. But the most significant figure in the piece is a Black woman. She is seen in silhouette at the bottom of the frame, her eyes her only visible feature. Her hands are held up and pressed against the glass that contains her; her fingers glitter with moons, stars, and astrological symbols. The Black woman is looking out at us—a kind of forceful looking. We are welcome to look at her, too, but we’re not allowed inside: this is her world, her life, and it’s dense with waking dreams and possibilities.

“Black Girl’s Window” (1969).Art Work © Betye Saar / Courtesy the artist / Roberts Projects / MOMA

Saar’s breakthrough works couldn’t have come at a better time. Los Angeles was waking up to its Black artists. In 1967, two brothers, Alonzo Davis and Dale Brockman Davis, founded the Brockman Gallery, which featured Black and other minority artists. The following year, the great painter Suzanne Jackson opened Gallery 32, where she showed works by the then relatively unknown David Hammons, the visual poet Senga Nengudi, and Saar. Artists moved between the two galleries; this was more about community than capital, and community bonds were strengthened by the era’s many upheavals: the Watts rebellion, the radicalism of the Black Panther Party. The escalation of violence and racial injustice made Saar want to push back. “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” did just that. As Saar says, it changed “a person of servitude to a soldier, to a fighter. Fighting for political rights. For personal rights.” She calls “Aunt Jemima” her first politically explicit work, but I would argue that it wasn’t. In the designs she created for Brown and Tann and in her early assemblages, there is already an awareness of what it means to look out at a world that looks back at you with its own twisted vision. The Mammy figure is, of course, a distortion of the Black female body. (The scholar Patricia A. Turner has described racist dolls and figurines like the ones that Saar uses in her work as “contemptible collectibles.”) Saar worried, at first, about how the work would be perceived by a white audience and how that might influence “the ways in which Black people saw each other.” She added, “What saved it was that I made Aunt Jemima into a revolutionary figure.”