US startup Strangeloop Studios first came to Music Ally’s attention in 2020, when it was part of that year’s Techstars Music accelerator.

The company was creating “original music-based digital characters with their own identities” according to its pitch for the accelerator’s demo day.

The plan was to launch the artists on social media, then release music – the company stressed that while the artists were virtual, all the music would be made by humans – with the ultimate goal of putting the avatars on stage for concerts.

Strangeloop Studios’ background was in concert visuals and short films for artists including The Weeknd and Kendrick Lamar, so it knew the live space. But its main challenge – like all virtual-artist startups – would be getting enough fans to connect with its characters to provide a launchpad for those grander ambitions.

Fast forward to 2023, and CEO Ian Simon is talking to Music Ally about how that went, what Strangeloop Studios has learned, and how this has helped it to evolve what it’s trying to do with this technology.

“We became very enamoured of the concept of virtual artists in 2018 or 2019 watching projects like Lil Miquela. We had been talking with Crypton Future Media who does Hatsune Miku, and we had done 3D concerts with Flying Lotus,” he says.

“We had this germ of an idea that there was going to be this explosion of virtual talent, and there were going to be massive online communities looking for real-world touchpoints to see these IPs that they’d become accustomed to digitally, in the physical world.”

At the same time, Simon had been talking to a number of artists who had unreleased music that they didn’t really want to put out under their main name / project, because it was exploring a new musical direction and/or because the thought of launching a brand new side project was daunting.

“We thought, okay, having a primarily audio-visual project would be a great solution for musicians who just wanted to get their music out into the world,” he says now. Strangeloop’s existing concert-visuals business would provide a stable base while the company did Techstars Music, raised funding and started to put its virtual artists out there.

Enter, stage left, a global pandemic.

‘You still need some feeling of organic connection’

“Very promptly, within a two-week period, all of our concert visuals work disappeared because of Covid!” says Simon. Luckily, Strangeloop had secured that first funding round by then: “So when our revenue went to zero, we were still able to fund our operations for the year.”

However, as the company got to work, building all its content within the Unreal Engine game engine to make it as transferrable as possible, it discovered that despite existing examples of popular virtual artists like Gorillaz and Hatsune Miku, building an audience for new ones was tough.

Simon describes “the demands on content and the desire for audiences for a really organic experience” as two key barriers that the company encountered.

“The Gorillaz were one thing, because they had this really concrete vision from the ground up with Jamie Hewlett and Damon Albarn, and it’s just not that easy to replicate, even if you have great talent on the musical and visual side,” he says.

“One of our characters had a modicum of success. He has over 100,000 followers on TikTok, he’s played for over 40,000 fans around the world, but it still didn’t have the feeling of genuine fandom.”

“It was more like a project that people were interested in. And what we realised was you still need some feeling of organic connection to the creator behind the project.”

It’s not that this is impossible. Simon cites virtual artist Teflon Sega as one example of success, unusual in that his streaming audience (more than 324,000 monthly listeners on Spotify) matches his social audience (336,000 followers on Instagram).

“You can feel that it’s one or two people collaborating to make these characters happen, and they were able to be creating content on a daily basis,” is what Simon admires about that and similar projects. But he says that the boom in virtual artists that he’d anticipated has yet to happen.

“One thing I feel I’ve been saying for three and a half years now is we’re still waiting for the real rising tide of virtual artists to enter the mainstream. It’s still relatively niche, and there’s only a few successes that have made waves enough,” he says.

“I still find myself explaining from the ground up, like a 15-minute spiel about what the hell I’m talking about! In 2020 I was hoping that by late 2023 more people would know exactly what I was talking about from the jump!”

‘The level of viewership and fandom is pretty shocking’

This has sparked… well, not a hard pivot, as such, but a refocusing of what Strangeloop Studios wants to do with the technology it has developed. The new strategy is less about creating everything in-house, and more about working with external partners.

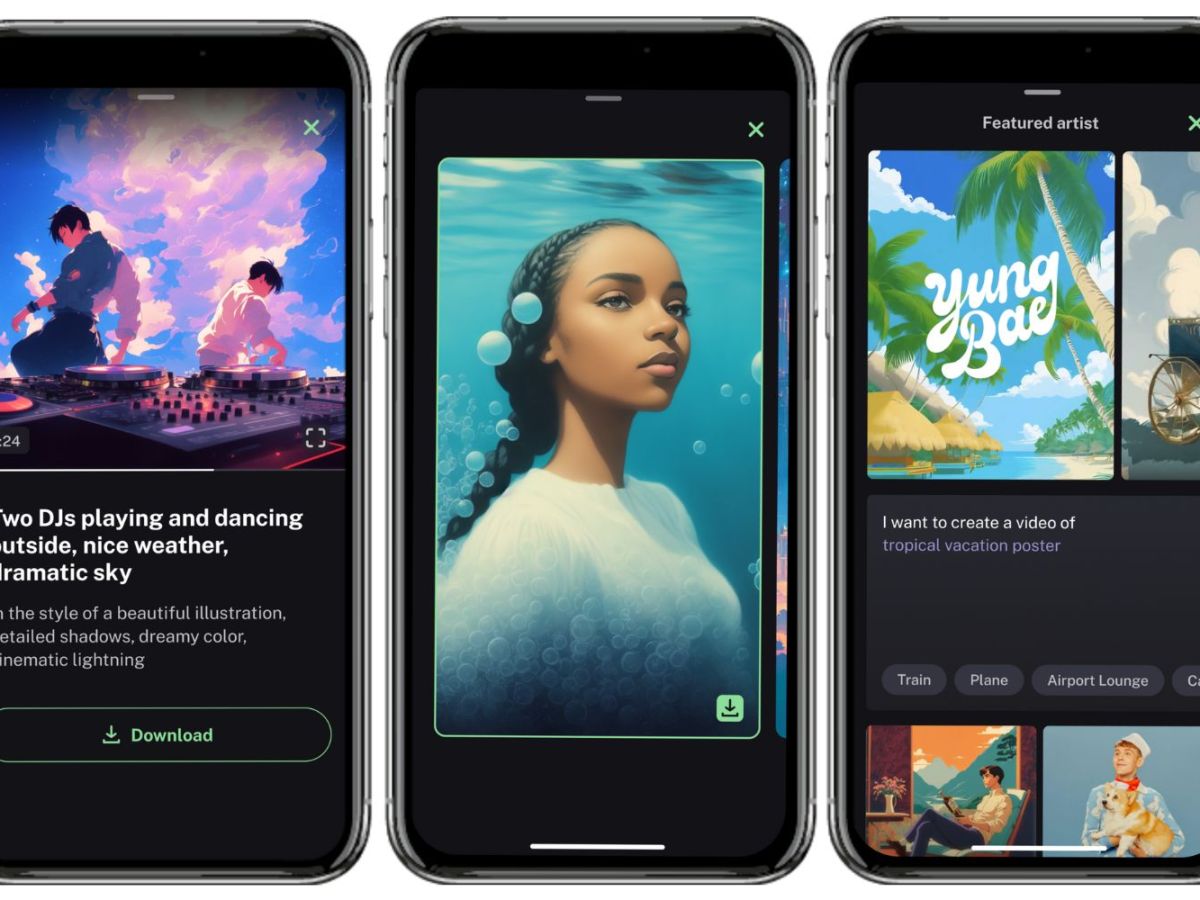

“We’d always dreamed of that everything we were building would eventually be externalised as tools for other people to get into the virtual artists world,” says Simon, adding that Strangeloop now thinks of its own virtual artists – LV4 for example – as the guinea pigs for what other musicians can do with its tools.

“At the beginning of this year we started to look towards, okay, how can we start taking what we’ve built for our own characters – which we battle-tested through launching LV4, which was our crash test dummy – and start working with other people who are trying to launch characters?”

Who might that be? Strangeloop has been talking to music rightsholders, including labels, who might be interested. But it’s also talking to individuals: musicians interested in creating a virtual persona, but also creators in one of the most interesting digital-media trends of recent years: vTubers.

That’s when people livestream on platforms – often YouTube or Twitch in the western world – using software to replace their face and body with an avatar. It’s a virtual character being digitally ‘worn’ by a human, if that makes sense.

“The level of viewership and fandom is pretty shocking to me. I think it’s only a matter of time before more people are talking about it. There are some crazy stats,” says Simon.

“Something like seven of the top 10 female streamers streaming gaming on Twitch and YouTube are vTubers who aren’t streaming as their actual face: they’re streaming as little anime characters. “And a massive portion of people who are launching their careers as vTubers are also doing music.”

Cue an opportunity, especially for vTubers who have used relatively simple tools to create their avatars, and are reaching the audience and income level to want to take the next step up in quality. And perhaps also to take their avatars into the live arena.

“We’re seeing more and more of these vTubers look at their success and be like, okay, I am motivated to invest in my own career, and up the quality levels so that my fans have a better experience,” says Simon. “We feel like our pipeline is in a place where we can offer these services at a triple-A level.”

‘So much of a musician’s success is linked to what they look like’

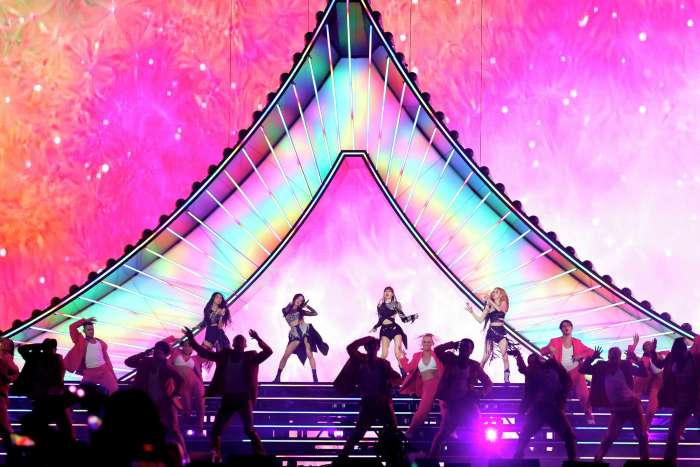

The company still works in the live-visuals sector – it worked on Blackpink’s latest tour (pictured above) for example, in a partnership that expanded from an original deal based on the K-Pop stars’ Coachella festival set.

Strangeloop Studios’ new strategy is to make the pipeline of tools and technology that it was building to launch its own virtual characters available to partners – labels, musicians and vTubers alike (“and eventually, hopefully, even to consumers) – to fulfil their own creative ambitions.

“It was not a big leap for us to think about, as people are trying to get into the virtual artists space, to take what we’ve learned and say ‘well, how can we help steward you through the process?’,” says Simon.

He stresses that none of this indicates a dampening of his original hopes that virtual artists would have a big impact on the music industry, even when large parts of that industry are still sceptical that these characters can cut through.

He tells the tale of a call with an artist manager who interrupted his pitch halfway through to tell him forcefully that “there’s no way that some 3D character is ever going to get people to care about them”.

But Simon comes back to the idea that there are still many artists who could make use of this technology to reach a wider audience with their music than the industry is perhaps willing to let them.

“Especially in today’s world – so much of a musician’s success can be so directly linked to what they look like. Obviously that’s been a thing for a long time,” he says.

“But I think it’s also more true in today’s content ecosystem than it was 20 or 30 years ago, when you could have these rare anonymous artists like Burial, where it was more about their music. Obviously that’s not a pop star!”

He suggests that Daft Punk might be the biggest example of an artist having massive success without their real faces being a key part of their image.

“But that is validating for the idea of virtual artists: if there is something that people are resonating with, they don’t necessarily need a conventional human visage to be attached to,” says Simon.

“I feel confident that there’s plenty of amazing music that has not made it into the mainstream because somebody somewhere decided the vehicle – aka the person who was singing it – was not pop-star material.”

He suggests that this is simply a logical extension of what has already been happening in the music industry, where the technology to make music became more and more accessible and affordable.

“It’s not that different from, like, GarageBand into Logic into Ableton, where suddenly you have this renaissance of people being able to make high-quality garage recordings, and have the Lil Nas X’s of the world go from zero to 60 very quickly,” he says.

“That was already something that the music industry was grappling with, and this to me isn’t foundationally different from that. It’s just adding a visual element on top of the already-democratised access to music production.”

Source link