NEW YORK — For almost three decades, Alan Michelson (Mohawk) has produced, spoken on, and curated artworks and exhibitions that attend to place, histories, and futures, and the lived realities of Indigenous peoples in North America. Michelson, who is perhaps best known for his site-specific mixed-media video installations, centers narratives often erased through the mechanisms of settler occupations of the so-called Americas. As the artist shared in a recent interview with Hyperallergic, he grapples with “the brutal, ongoing legacies of colonization.”

Michelson, who grew up in Massachusetts, gravitated to art at age seven while taking his first art class at Wistariahurst, a historic home in Holyoke. “The museum stoked my imagination as much as the class, and art lodged in my imagination as a cocktail of nature, place, and history,” he explained. After high school, he enrolled at Columbia University before pivoting to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (SMFA, part of Tufts University), where he earned his BFA in 1981. “The Museum of Fine Arts was the second museum I got to know after moving to Boston at age nine,” he noted. “Its delights were exponential.”

Although Michelson reflects fondly on his time at SFMA, he did not encounter the artworks and movements that later defined his practice. “I was not exposed to the kind of work that later drew me: site-specific installation and conceptual, critical art,” he stated. “One is usually taught by the preceding generation and exposed to their zeitgeist, which at the museum school, was largely formalist modernism.” As a result, his education gave him a foundation for his career, but did not represent the entirety of what he wanted to accomplish. “I learned how to make something beautiful there, but I wanted more […] I was after forms of beauty that could confront the ugliness and injustice of the world, and not just be a vacation from it.”

Michelson’s work does just that, creating rich environments for the viewer to enter — alternating between aesthetic beauty and damning testimonies of colonial occupation. In the 1980s, he designed book covers for a small press in Cambridge, Massachusetts. During that period, his painting began shifting away from what he calls “nature-derived abstraction” and moving toward “large, encrusted, representational canvases,” influenced by the likes of Anselm Kiefer.

Upon moving back to New York, his work defiantly sat apart from art world trends, and from the Indigenous art being exhibited at the time. “Unlike now, at that time there weren’t a lot of artists who were working like I was,” he said. “Focusing on land and site, researching, and surfacing their histories, and allowing those discoveries to suggest artistic choices.” Michelson began to get noticed. “An artist friend brought Lorcan O’Neill, who then worked at Barbara Krakow Gallery, to my studio to see my work,” Michelson told me. “[O’Neill] put me in a well-received, three-person show at the gallery in 1986. That show, and an NEA grant in painting, launched my career.”

Today, he boasts an impressive record of exhibitions, writing, and teaching, as well as co-founding Indigenous New York at the Vera List Center, alongside Amanda Parmer and Jackson Polys (Tlingít). But what remains constant for Michelson is his connection to the land and acknowledgment of place — in terms of place-keeping as opposed to place-making — as he dives into the aggregated and lush history of the continent before contact. “I’ve always strongly connected with, and been curious about, the places I’ve lived, and connection to place is fundamental to Indigeneity,” he asserted. “As much as I love the Manhattan that is, I lament the Manahatta that was,” remarking on the biodiverse archipelago that previously existed. “The landscapes I addressed [in early work] are the same landscapes I address now, namely those of Turtle Island, however ravaged or overrun.”

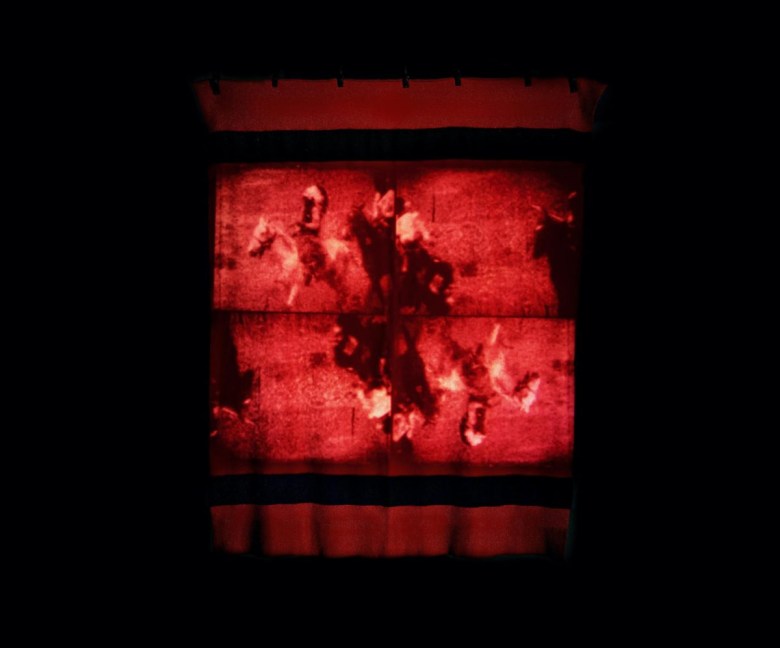

Michelson’s video work, which he began in 2001 with his first time-based piece, “Mespat,” straddles the line between sculpture, video, and painting. “Mespat” was part of a large-scale installation featuring a screen composed of white turkey feathers, onto which the video was projected. The video is a single shot panning a 3.5-mile stretch of the Newtown Creek in New York City, an estuary known as “Mespat,” which means “bad water place” to the Lenape people. The creek, which divides Brooklyn and Queens, is the site of a 17-million-gallon oil spill in the mid-20th century. The work has an almost dreamlike aesthetic at odds with the freighted reality it depicts. The feather screen’s large scale and its painterly quality summon allegorical European history paintings while illustrating the sustained humanitarian and environmental damages caused by European occupation of the Americas.

The artist’s practice of projecting onto found or altered readymade objects has led to projections on a bust of George Washington and three tons of oyster shells. With no formal training in sound or video, what Michelson has been able to create is pure alchemy. “I like video’s grounding in photography and the real, its documentary aspects, but also its energetic properties as colored light and sound waves,” he expressed. Projecting a moving image onto a solid object — uniting stasis and motion — creates “something more unexpected and evocative.”

Michelson’s work leans into the power of art as a visual language, one that can generate emotional and intellectual responses while simultaneously illuminating histories that are obscured by settler-colonization, capitalism, and patriarchal structures. As the artist shared, “art can deliver this history in a nuanced, potent form that can stir both mind and heart, and lift the amnesiac pall over American history.”