In May 1638, following a devastating famine and drought, the Pocumtuck people — of what is now Deerfield, Greenfield, and Shelburne Falls — brought 100 bushels of corn in 50 canoes down the Connecticut River to help starving English colonial settlements below Hartford.

The corn, also known as maize, was a primary source of sustenance at the time.

While the encounter has been published in colonial records — and by historians in the late 1880s and early 1890s ― it has been understood through a Eurocentric lens, and not brought to a wider audience, according to anthropologist Margaret Bruchac.

Bruchac, Indigenous artists, and local organizations have been working to highlight the encounter to show the history of Indigenous generosity — and to encourage a different way of thinking about the past.

“Until I started looking into this story and trying to make people aware of it, there was an assumption that colonial settlement, domination was inevitable,” Bruchac, who is Abenaki, and is a professor emerita in the University of Pennsylvania’s anthropology department, told MassLive. “In the valley, there was also an assumption Native people here just kind of rolled over and sold the land and let colonists come in and that wasn’t true either.”

Bruchac said American history has been distilled into received myths about European dominance and Native vulnerability without understanding the complexities of what was happening on the ground.

While Bruchac said she runs public programs and walking tours in Deerfield and has published and researched the encounter in her 2007 dissertation at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the story also has been brought to a wider audience through Seaconke Wampanoag artist Deborah Spears Moorehead.

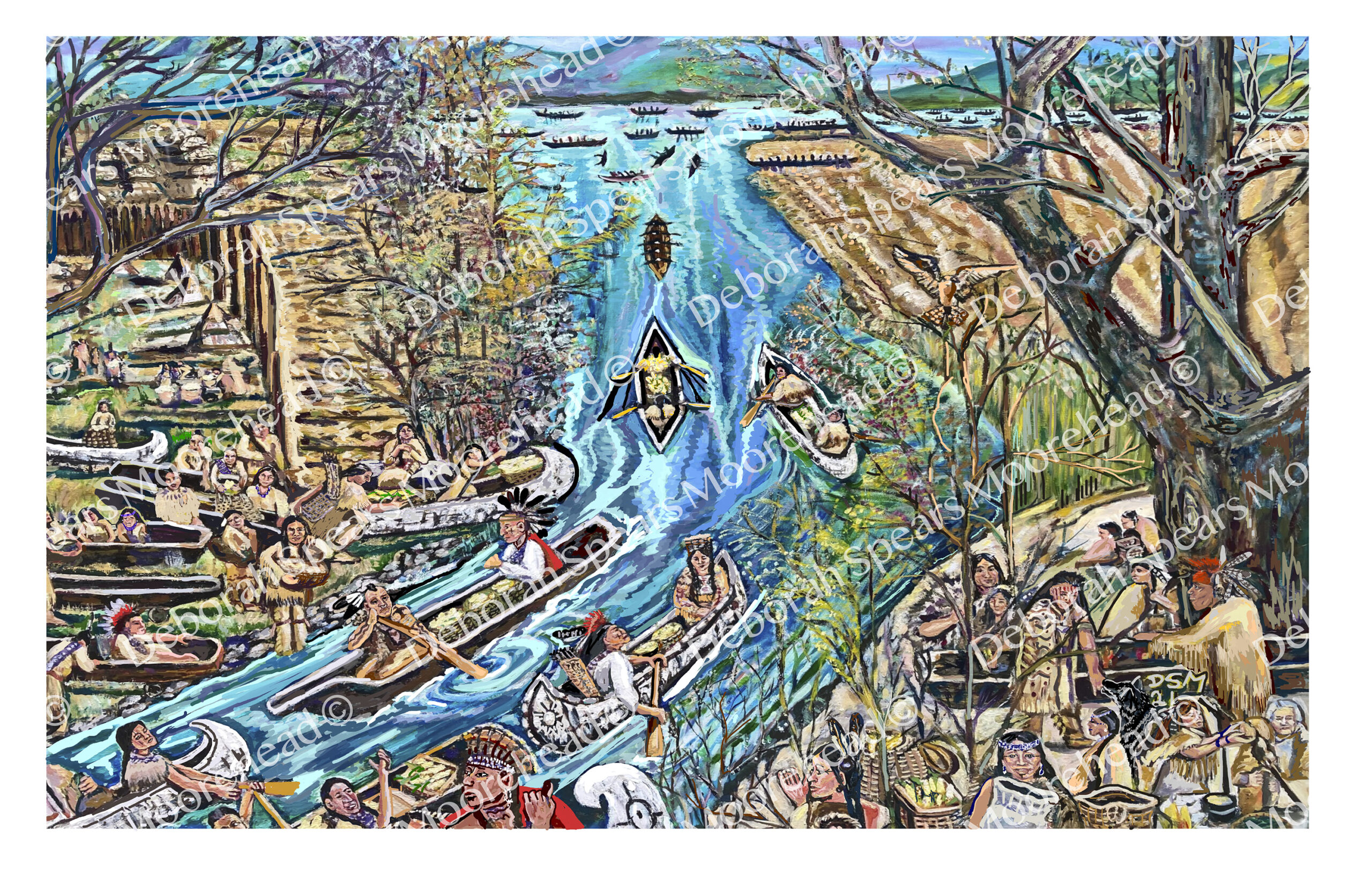

Spears Moorehead interpreted the historic event in a colorful painting entitled “50 Mishoonash.” The Wampanoag word “mishoonash” is used in the painting’s title to identify the dugout canoes.

“I think one of the important points of this 50 Mishoonash painting is to portray how the Pocumtuck like the Wampanoags gave their food to the colonist[s] to save their lives,” Spears Moorehead said.

Spears Moorehead said despite Indigenous generosity, the U.S. government has continuously taken from Native American tribes, with many not being tribes not being federally acknowledged or recognized.

The painting was commissioned by the Nolumbeka Project, a local organization promoting the region’s Indigenous cultures and histories through the work of Jennifer Lee and Diane Dix who are on the board of directors.

“I was completely blown away because we just don’t hear these great stories. It wasn’t ever part of our history lessons,” Lee said. “I think it’s very important because of the place that it happened. We can still go to the place that happened. We can go to the mountain that happened under and it really shows a lot about the Native people of the area.”

Lee said the painting demonstrates not only the fertility of the valley but also the Indigenous knowledge of cultivating corn and storing the food in giant pits in the ground lined with clay.

She said the Nolumbeka project commissioned the painting to help young people and adults visualize what happened and bring the history to life.

“Every time I go over the Calvin Coolidge Bridge and I see the Connecticut River, I see those 50 canoes delivering corn. And it’s just quite amazing, I still wonder how did they keep that corn dry?” Lee said. “I was given the impression growing up that Native technology what wasn’t even called technology — Native ways were the backward ways. But I find them to be the forward ways, the ways we need to live in order to survive on this planet.”

The painting is now housed at the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association.

“I think when you look at it, if you don’t know anything, you see a lot of people. You see men, women and children. You see people are happy. Nobody looks like they’re getting ready for war,” Bruchac said. “There’s just an abundance of everything. And that’s what I love about that image is it gives you this snapshot of a richly layered and complex society of happy, healthy people in the midst of an ecosystem that gives them whatever they need to survive.”

Since the 1990s, anthropologist Bruchac has been working to understand and uncover the “vanished Native history” of New England.

Bruchac said that during the encounter of 1638 there were no English settlers in the Pocumtuck territory. And it was the English settlers at the time who were in a difficult position — not the Indigenous people.

“Pocumtuck could’ve just said no. And when I fantasize about the past, there are moments that I think, perhaps they should have because it would have changed everything,” Bruchac said. “They would have packed up and gone somewhere else.”

But Bruchac said the Indigenous people saw the English settlers not as individuals who would destroy their territory, or take over their land, but as refugees or immigrants trying to survive on foreign land, especially because of how small the populations of English settlers were.

“With that in mind, if communities — if they felt strong, stable enough — were willing to say here, take this piece of land, create your town, we’ll live together,” Bruchac said.

The English paid the Pocumtuck people in wampum, which began the trade relations between the Pocumtuck and English settlers.

“Until I really sort of stepped in to understand this from a Native perspective, from an Indigenous perspective, people saw it and historians tend to see it as a purely economic interaction,” Bruchac said. “That is not how Native communities operated in that time period.”

Bruchac said Native people were heavily invested in reciprocal kinship relationships, so even when there were conflicts between or within communities, they were largely resolved without warfare.

“What happened afterwards was not the kind of generous new relationship that Pocumtuck I’m sure hoped for. What happened instead was new conflict,” Bruchac said.

Ever since her dissertation, Bruchac said she has been working to help the public understand who Native people were — not just why they aren’t here presently.