Press play to listen to this article

Voiced by artificial intelligence.

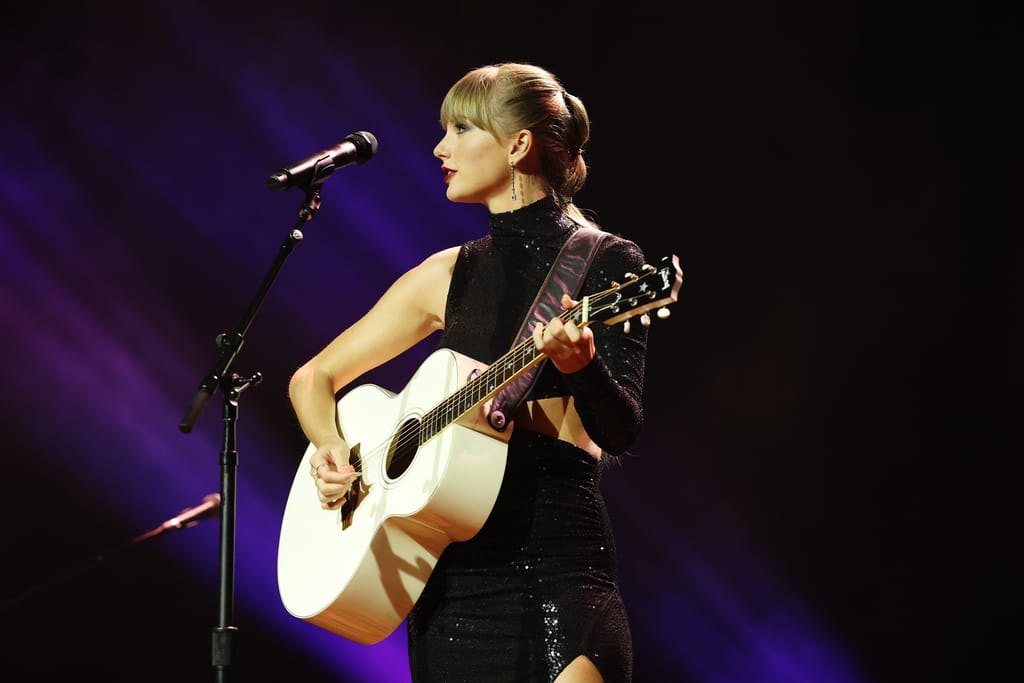

Music streaming platforms like Spotify should brace themselves for a fresh round of scrutiny. A key lawmaker in the European Parliament’s culture committee wants to make streaming giants better remunerate and give more visibility to European music creators and artists.

“There is a loophole in our regulation. We need to fill it,” Social-democratic Spanish lawmaker Iban García del Blanco said in an interview. He is drafting a report that he promises will be “intrusive in this market” because “it is the most unbalanced sub-sector of the cultural sector at the moment.”

The European Parliament’s move to call out Spotify and its peers highlights the frustrations of singers, artists and performers that they have been left in the cold by EU rulemakers, as streaming giants increasingly took over the industry in past years.

The Spanish lawmaker backed calls to better distribute revenue from leading streaming platforms to the industry’s creators. García hopes his report — while non-binding — will compel the European Commission to fix the problem.

According to Véronique Desbrosses, the general manager of GESAC, which represents organizations collecting royalties on behalf of authors and composers in Europe, “the problem is that this music market is not regulated at all at the European level.”

Streaming “has become the main route to access music, and it cannibalized the other ways,” which has put artists at the mercy of platforms, she argued.

Spotify, which is headquartered in Sweden, is hardly alone. While it had the highest global market share for music streaming (31 percent) in 2021, its competitors include Apple (15 percent), Amazon (13 percent) and Tencent (13 percent).

“We are talking all the time about Spotify, but there are many more examples, sometimes more influential,” García said. “TikTok is one of them as it settles a new way to listen to music” in under 30 seconds, he said, pledging to fight this “impoverishing” new model.

Olivia Regnier, Spotify’s director of EU regulatory affairs, said she was happy to have this debate but regretted that it began “from the premise that there is a regulatory gap to be filed, without asking what the problems are.”

Sharing the pie

Remuneration is expected to dominate lawmakers’ work on the report. The 2019 copyright directive introduced a principle of “appropriate and proportionate remuneration” but the size of the pie — and the actual money that goes to artists and creators — has yet to meet their expectations.

“We’re not paid decently. You need to have tens of thousands of streams to have a little bit of something,” Desbrosses said.

Last November the United Kingdom’s competition watchdog published its own study of the market, finding that the top 0.4 percent of artists accounted for over 60 percent of streams. The British regulator however also outlined that “neither record labels nor streaming services are likely to be making significant excess profits that could be shared with creators.”

Roughly a third of what a consumer pays to stream music is kept by the platforms themselves. The rest goes to labels and collective-management organizations before making its way into the pockets of artists. British lawmakers in 2021 estimated that about 16.5 percent goes to performers and 10.5 percent to the author and the composer of a song.

Spotify’s Regnier stressed that platforms have very little power or visibility over how much money actually trickles down to creators.

What’s more, “none of the streaming platforms are profitable,” stressed Regnier — who also chairs Digital Music Europe, a lobby group representing other services like Soundcloud and Deezer.

“We’ve been criticized for not raising the price, but we started out in the face of piracy, and we’re still facing it,” she added, insisting that investments were still required to keep streaming services attractive enough to beat pirate platforms.

For GESAC’s general manager Véronique Desbrosses, Spotify’s choice to invest in its global expansion is what’s actually holding back proper remuneration and comes at “the expense of the value of music,” she said.

Transparency wanted

Artists also want more transparency from platforms about how they actually work.

“The problem is that we don’t know how the recommendation tools are made. What we know is there are processes that are not acceptable,” Desbrosses said. She cited one feature introduced in 2020, called Discovery Mode, which allows performers to get boosted exposure on the platform at the cost of lower royalty rates.

Regnier insisted it was one functionality among others and artists were free to not participate. “We provide as much information as possible” about algorithms, Regnier added.

While the audiovisual industry benefits from quotas for “European works,” the music-streaming players are also not under any obligation to promote European songs. “We want a reflection that goes into that direction,” Desbrosses said.

The film and the music industries should also not be treated the same way, Regnier argued. “European music has always done well,” she said, pointing to a London School of Economics study showing that 70 percent of the most popular songs in Poland in 2022 were Polish, for instance, compared with 10 percent in 2012, according to Spotify’s figures.

CLARIFICATION: This article has been updated to show that the study cited by Olivia Regnier was conducted by the London School of Economics.