It’s not like all Native stories are sacred. Natives like to spin a good yarn like anybody else, telling jokes, fables, or raucous tales of the trouble their buddies got into. But Native people are, without question, storytellers. That’s part of the heritage. And sacred or not, Native stories are special. They build bonds. They can heal trauma, or preserve suppressed traditions and histories. Some carry teachings that help guide Native children so that their minds and actions match their cultures. Stories can also be hazardous in the hands of the wrong person. Some might be inappropriate to a listener who’s too young, or outside the tribal culture, or uninitiated into a certain life path or profession. Some must be told exactly as the elders told them—like reciting Shakespeare.

On Savage Shores: How Indigenous Americans Discovered Europe, Caroline Dodds Pennock, Knopf, 320 pp., $32.50, January 2023

Most ancestors Indigenous to North America didn’t leave their most sacred stories lying around in books to be misinterpreted and abused. They safeguarded these treasures carefully through oral storytelling. This makes some Native stories extraction-proof, transferred only with intention and consent. When a Native person receives a story, they’re taking on a responsibility—to tell that story right, to protect it, and to be accountable for wherever it goes and whatever damage it might do. You can’t get a Native story without first earning the storyteller’s confidence. If you tried to force one out of a Native person, they might fill your ear with bullshit just for kicks—and maybe charge you a hundred bucks for the “sacred knowledge” you just acquired—only to go off and tell that story to their cousins for a laugh. Because stories are unextractable, they’re one of the last resources over which Native people have theoretical and practical sovereignty. And that sovereignty is sacred.

On Savage Shores: How Indigenous Americans Discovered Europe, released earlier this year, is an attempt by British historian Caroline Dodds Pennock to dig through European historical records from the age of tall ships, searching for Native stories. The author pores over old papers, tracking down Indigenous people who lived in the shadows of colonizers as slaves, “wives,” and diplomats, their presences appearing quite literally in the margins of maps, receipts, journal entries, and other loose bits of detritus. The written records, however, tend to say very little about these individuals. The glimpses we get are filtered through the colonial gaze: sometimes paternalistic or gawking, other times overtly racist, scanty, and usually of dubious accuracy.

But the records say volumes about Europe’s belligerents, making this effectively a book about colonizers: figures like Hernán Cortés of Spain and his greed-addled ilk, along with their enablers, including King Charles V, Queen Isabella, various popes, and the Spanish courts. Spending a lot of time with these figures is not very fun or illuminating for an Indigenous reader. Of course, Indigenous readers will likely be turned away by the book’s title, which uses a racial slur—despite the author’s attempt in the preface to justify it as an ironic inversion.

Pennock is clear about her good intentions—that she wants to see Native people empowered and represented, the agency of these individuals and their contributions to global history finally acknowledged by academia. But the quest has sent the author to the outer limits of what European-style academic research can accomplish, trying to dismantle the master’s worldview using the master’s tools. Her efforts terminate in a cul-de-sac. Obsession with paper documents can only go so far, and this fundamentally white approach simply ends up re-platforming historical white men.

Sometimes, the result is benign—we learn some interesting things about 16th-century Spanish laws and politics around slavery, for example, and there’s a brief respite where Pennock explores the history of Native North American first foods in Europe (“Irish” potatoes and “Italian” tomatoes, for instance)—but other times it’s re-traumatizing, as when Pennock quotes from a colonizer’s detailed description of his rape of an Indigenous woman.

These maneuvers reflect the European value of academic detachment but do little to illuminate the Native stories Pennock is after. The text sweeps the historical grounds with its searchlight of the white gaze, only to find that most of its Indigenous subjects have already escaped.

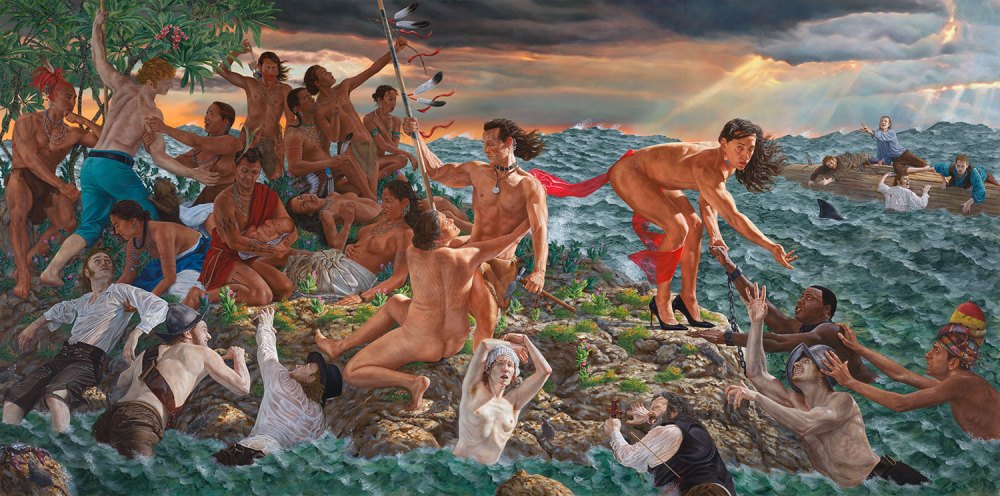

Miss Europe (2016) is part of Monkman’s series The Four Continents, which riffs off a series of the same name by 18th-century Italian painter Giambattista Tiepolo. Each painting in Monkman’s series examines Eurocentric misconceptions about the world’s regions and explores themes of colonization, globalization, and exploitation.Kent Monkman

In 1584, as Pennock recounts, two Coastal Algonquin men named Wanchese and Manteo became translators for a British colonizer. They were the first of many Algonquin-speaking people to visit London—whether as travelers or captives is unclear.

Though the records say almost nothing about what Wanchese and Manteo did in London, we spend pages reading about what English gawkers thought about them, which queens and courts they were probably presented to, and what ridiculous European costumes they might have worn (willingly or not). Pennock pauses periodically to wonder what they must have thought of all this, speculating that it’s “likely that they were startled by the magnitude of the city, the teeming streets, and the expansive stone structures dominating the landscape.”

Pennock demonstrates that it was Wanchese and Manteo who were responsible for the English-Algonquin translations that European men took credit for. It’s the author’s way of transferring agency from the colonizer to the Indigenous people who did most of the work—a small justice to the two travelers, but not without its own shades of white saviorism. This attempt to bestow agency is central to the objectives of the book, a continuation of five centuries of missionaries, policymakers, and teachers who believe it’s their job to help Indigenous people.

In 1585, after getting some head pats from his monarch, the colonizer who brought Wanchese and Manteo to London went back with them across the Atlantic to do a little more colonizing. He ran his ship aground off the coast of Roanoke lands, and Wanchese promptly split, escaping back to his homelands to rabble-rouse against the colonizer he had sailed with. “He had apparently had enough of English hospitality,” Pennock writes. “Once Wanchese leaves the oversight of the English, he also largely disappears from the sources, making it hard to trace his later life,” she adds, with what might be a whisper of ruefulness. Indigenous readers, if there are any, will more likely jump up and cheer at this point: Go, Wanchese! You did it, man! Whether he went on to foment resistance, as Pennock suggests, or marry his true love, or get eaten by alligators, that’s Wanchese’s story. And he managed to keep it out of the white gaze.

The white gaze has trouble with object permanence. But Native histories do exist, and Native agency exists, whether or not European-descended people are able to document, organize, categorize, or define those things.

Monkman’s painting Miss Chief’s Wet Dream (2018) depicts the Guswenta or Two Row Wampum Treaty, a Haudenosaunee-Dutch alliance formed in 1613. The scene mythologizes early relations between Indigenous people and European settlers.Kent Monkman

In 2017, the photographer Josué Rivas (Mexica and Otomi) gave a TEDx talk in Rapid City, South Dakota, about the importance of Indigenous people telling Indigenous stories. It was the year after the start of protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock, where he had spent six months documenting Indigenous resistance. “We were in charge of our narrative, and that was powerful,” he said. “That’s how we create our reality of our people.”

Rivas’s photographs focused on resilience and prayer instead of controversy and conflict, presenting, in his words, “a side of the story often overlooked and misunderstood by the non-Native photojournalists.” Native documentarians operate differently, Rivas said, out of respect for protocol and cultural boundaries, by avoiding extraction and even sometimes putting down the camera to participate in ceremony. “By telling our own story, we are reclaiming our identity and healing our historical trauma.”

On Savage Shores is a white story about white stories about Natives—even if it is critical of colonizers. Again and again throughout the narrative, Pennock pauses to wonder what the Indigenous subjects must have felt or thought. She’s careful never to speak for them and keeps a short leash on her imagination. But at no point does she consult contemporary Native scholarship. Only after 213 pages, in the very last chapter, do we finally hear from any named Native people at all—Red Shirt and Black Elk, two historical figures, quoted via white people who may or may not have recorded them accurately.

Ógle Šá, aka Joseph Red Shirt, was a complicated figure. He served in the U.S. Army and enrolled his own children in the government-run Carlisle Indian School’s inaugural class. He opposed Native resistance movements such as Ghost Dance and those of Lakota leader Crazy Horse; white folks considered him progressive for it. He also traveled with Buffalo Bill Cody to England, where he exoticized Indigeneity for fawning crowds.

“In this double life, Red Shirt saw himself not at all as the gawkers imagined him,” Pennock writes (but not before she first quotes a white man, Buffalo Bill, on what Red Shirt “clearly felt” when meeting Britain’s Queen Victoria). “The chief spoke poignantly to an English reporter about the future of his people: ‘The Indian of the next generation will not be the Indian of the last. Our buffaloes are nearly all gone: the deer have entirely vanished; and the white man takes more and more of our land.’” Pennock chose this quote to underscore that Ógle Šá was not the dancing savage the English took him for. But she also inadvertently recycles the “vanishing Indian” trope—the myth in U.S. culture and politics that Native people are part of the past—with a quote which, even if it was transcribed exactly as Ógle Šá said it, serves the white agenda.

Heȟáka Sápa, aka Black Elk, was of a different political stripe. He was a leader in the Ghost Dance movement and fought alongside his cousin Crazy Horse. But he joined his fellow Lakota Ógle Šá on the trans-Atlantic voyage with Buffalo Bill. Pennock quotes Heȟáka Sápa about his motives for joining: “I wanted to see the great water, the great world and the ways of the white men; this is why I wanted to go.” The line originally comes from an interview with white poet John Neihardt for his book Black Elk Speaks, which has a questionable reputation for the degree to which the author likely massaged or misinterpreted Heȟáka Sápa’s words.

During their interviews, Heȟáka Sápa spoke in Lakota, and his son, Ben Black Elk, translated into “Indian English,” the intertribal lingua franca. Neihardt would repeat sentences back in standard English, and his daughter Enid would jot them down in shorthand. In some cases, Neihardt’s other daughter Hilda would type notes. These typed and shorthand transcriptions are the basis for white anthropologist Raymond DeMallie’s book The Sixth Grandfather, partly written as an answer to the dubious authenticity of Black Elk Speaks. It’s from The Sixth Grandfather that Pennock quotes.

So Heȟáka Sápa’s words reach us only after filtering through no less than five intermediaries—four of them white. Why not just talk to a Native person? Heȟáka Sápa has living relatives. There are Lakota historians working today. Instead, Pennock’s book presents Natives through layers of whiteness and relegates them to the past.

The question gnaws at the heart of On Savage Shores: Should a non-Native historian have attempted this book? There are effective ways to use colonial tools against colonialism, such as when researchers last year studied place names in U.S. national parks and found that they support settler-colonial mythologies and racism. Here, scholars were turning the white gaze (academic research) not upon Native people, but upon a white system (the National Park Service) with a critical eye. Pennock’s formidable research skills might have been better spent similarly deconstructing white systems of power.

As for the many other North Americans who crossed the Atlantic to visit Europe during early colonization, white academia may never know what they thought or felt, who they went on to love, and how they processed their trauma or described to family the horrors of uncivilized Europe, where class and gender disparities foreshadowed their own homelands’ capitalist futures. The gaze of whiteness cannot peer into those stories, despite what must be a frustrated longing to do so. Those Indigenous travelers kept their stories, and they’re heroes for it. That, perhaps, is the ultimate expression of Native agency, even if it’s not the one the author set out to discover.