“Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art,” the latest in cultural criticism from Lauren Elkin, author of “Flâneuse: Women Walk the City,” is intellectually rigorous and emotionally astute. Her supple narrative gives deep attention to a diverse gathering of second-wave feminist visual artists and writers, though her broad scope connects these women through time and lineage to past- and present-day artists, writers and themes. We’ve come far, and yet, what the women of this period were showing with their art continues to carry much meaning.

The structure of the book is not dissimilar from Jenny Offill’s 2014 hit novel “Dept. of Speculation,” from which “Art Monsters” takes its name. There is an elliptical, cellular quality to both books; in “Art Monsters,” Elkin adds an additional device—the slash. Each of the three main sections of the book is divided into multiple subsections, and within these subsections, several narratives are divided further by a single slash in the line break. Some segments consist of only one sentence, others an attributed quote, while still others elucidate the lives and works of women artists such as Carolee Schneemann, Lynda Benglis, Judith Scott, Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus, Hannah Wilke, Ana Mendieta, Sutapa Biswas, Kara Walker, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, and many more. The visual effect of this “slashing” is two-fold: slashes here create space around narrative and thought, but they also provide a kind of trail, as dominos falling into one another, each form separate from but dependent on the next for its motion. There’s another, more metaphorical meaning, built into the slashes, illustrated by Elkin’s discussion of suffragette Mary Richardson’s 1914 slashing of Velázquez’s “Rokeby Venus” at London’s National Gallery. The damage done to the canvas has long since been repaired, but the particular action remains profound.

Who gets to be an art monster? Elkin wants to know. She begins the book, and many sections, with a discussion of Virginia Woolf’s life and writing, particularly “Professions for Women” and “Three Guineas.” A genesis of sorts. Was Woolf an art monster? I’d wager so. Traditionally, though, men have filled the role of art monster, meaning they have been allowed to devote their lives to art, often to the exclusion of all other roles they might play. But by feminism’s second wave (circa 1965-1985), women artists were subverting expectations about who makes art, and what that art might look like. Ideas around what the subject/object/(artist) relationship could be began to transform as women pushed back against cultural mores that held them captive. The unruly body became a site of feminist intervention as women artists of the time used their own bodies and experiences to create art. From this shift in the art and literary worlds came the now mainstay idea that the personal is political. There’s an intimacy to this notion that Elkin gravitates toward and pushes into (also against) as she tells the stories and examines the work of her chosen art monsters; at her most incisive and provocative, Elkin calls for expansion rather than limitation. Art as testament and art as art. Where have we been and where will we go? A slash may separate but it also joins.

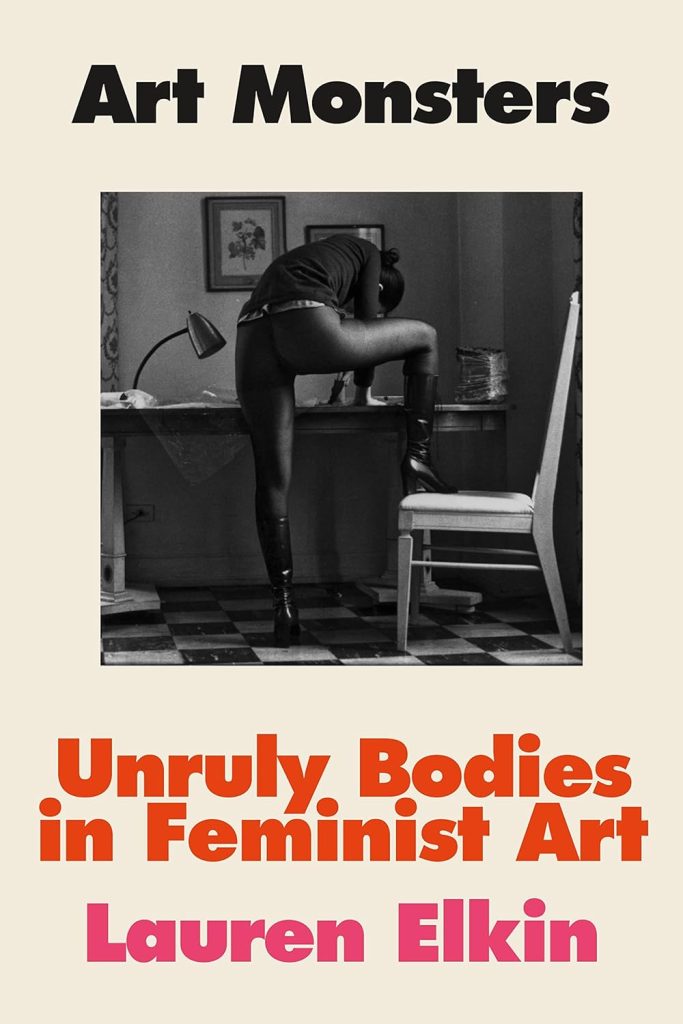

“Art Monsters” includes images of some of the artwork under discussion, and they are a welcome addition to the text, though Elkin is masterful in her descriptions. She is also compassionate, thorough, and discerning in her coverage of the lives and intentions of the women she features. Some of these women’s lives were catastrophically, even fatally, impacted by misogyny, facts that Elkin refuses to elide. By the end of “Art Monsters,” Elkin lands, via Vanessa Bell’s exuberant “Oranges and Lemons,” on the conviction that anyone—regardless of gender or station in life—can be an art monster. Here, as elsewhere, Elkin’s vision is surprising in the best way. Innovation, interrogation, and intersectionality combine to bring a new understanding of how fertile the unruly body has been and continues to be.

“Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art”

By Lauren Elkin

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 368 pages

Sara Rauch is the author of “What Shines from It: Stories” and the autobiographical essay “XO.” Her author profiles and book reviews have appeared in The Rumpus, Lambda Literary, Los Angeles Review of Books, Curve Magazine, and more. She lives with her family in Massachusetts. www.sararauch.com