Southern California artist Alexis Smith passed away at the age of 74 on Tuesday.

Smith was lauded for the wit with which she mined pop culture, Hollywood and the American West for her collage work — often at massive scale. She’d pair found imagery, texts and objects set against surprising framings and installations — memes long before her time.

“She emerged at a time when a generation of artists who were fueled by the ideas of conceptualism and pop art were just coming into maturity,” said the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego’s director and CEO, Kathryn Kanjo. “We can think about artists like John Baldessari or Ed Ruscha, with whom Alexis Smith would stand shoulder to shoulder. And I think that, like those three artists together, we can see a particular kind of dry wit that we think about as particular to Southern California pop.”

But, locally, her best-known work might just be a footpath.

Smith’s “Snake Path” is part of the UC San Diego Stuart Art Collection, winding up a hillside towards the university’s iconic Geisel Library. Installed in 1992, it’s a 560-foot-long, 10-foot-wide rendering of a serpent made from large, mosaic slate tiles, and it’s visible even from Google Maps.

The imagery of the serpent, a giant “Paradise Lost” book sculpture representing knowledge and the miniature Eden-like garden at the top all draw on ideas of innocence versus knowledge — and how those concepts play out on a university campus.

Students, staff and visitors walk directly on the snake to and from class or study sessions at the library.

Courtesy of the Stuart Collection

Mathieu Gregoire has worked with UC San Diego’s Stuart Art Collection since the 1980s and worked with Smith to bring “Snake Path” to fruition in the late ’80s and early ’90s. He said the work also represented a turning point for the Stuart Collection, an unparalleled collection of public art.

Courtesy of the Stuart Collection

“This was the first work in the Stuart Collection that was completely embedded in not just the physical landscape, but also the functional landscape, because it’s a pathway,” Gregoire said.

Other works have since been similarly constructed and functionally interwoven into the campus, including Ann Hamilton’s “KAHNOP • TO TELL A STORY,” a 2023 pathway inscribed with language.

“This was the first to do that, to really spread itself out not to be an object in a landscape, but to really embed itself within the landscape,” Gregoire said.

In a panel discussion with John Baldessari, Robert Irwin and others about the Stuart Art Collection recorded by UCTV over a decade ago, Smith said there was one crucial difference between public art and museum art.

“It’s not the art that’s different, it’s the audience that’s different.”

— Alexis Smith on public art

“One of the things that’s different about public art, and you see it in this collection particularly, is that it’s not the art that’s different, it’s the audience that’s different,” Smith said.

“Because when you put something in a museum or gallery, the audience is the people who know that it’s there and choose to go see it. And when you put something out in the world, you get everybody. And they didn’t exactly, necessarily want to see it or choose to see it or know anything about art or know anything about artists,” she said. “The art really has to speak for itself in that situation.”

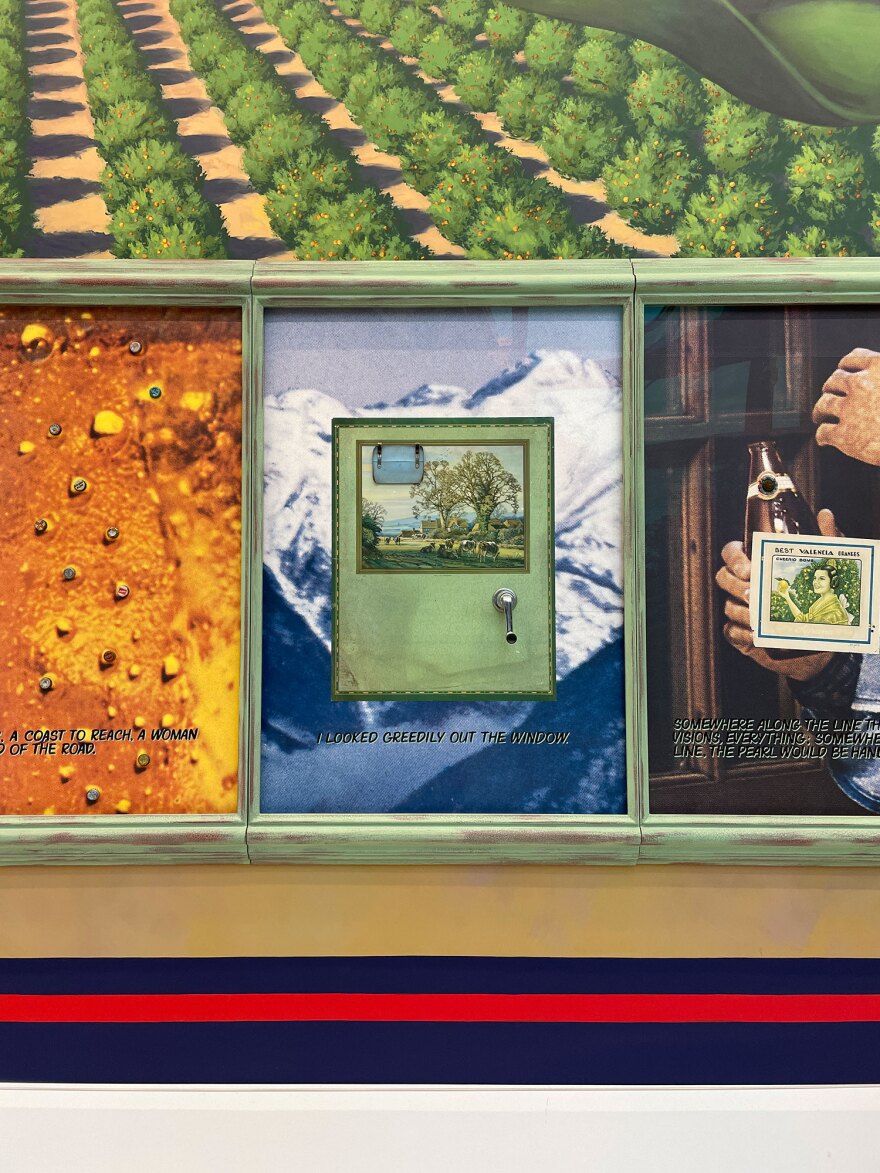

Smith also has another work in the Stuart Collection — the only artist to have two pieces in the collection. Her massive mural “Same Old Paradise” was originally installed temporarily at the Brooklyn Museum in 1987. The piece served as the inspiration for her “Snake Path,” so it brings her creative work full circle.

Smith was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2015. By the time the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego held a major survey exhibition of her work in 2022, she had been living with Alzheimer’s for seven years. The exhibition, “The American Way,” curated by Anthony Graham, celebrated Smith’s many decades of work.

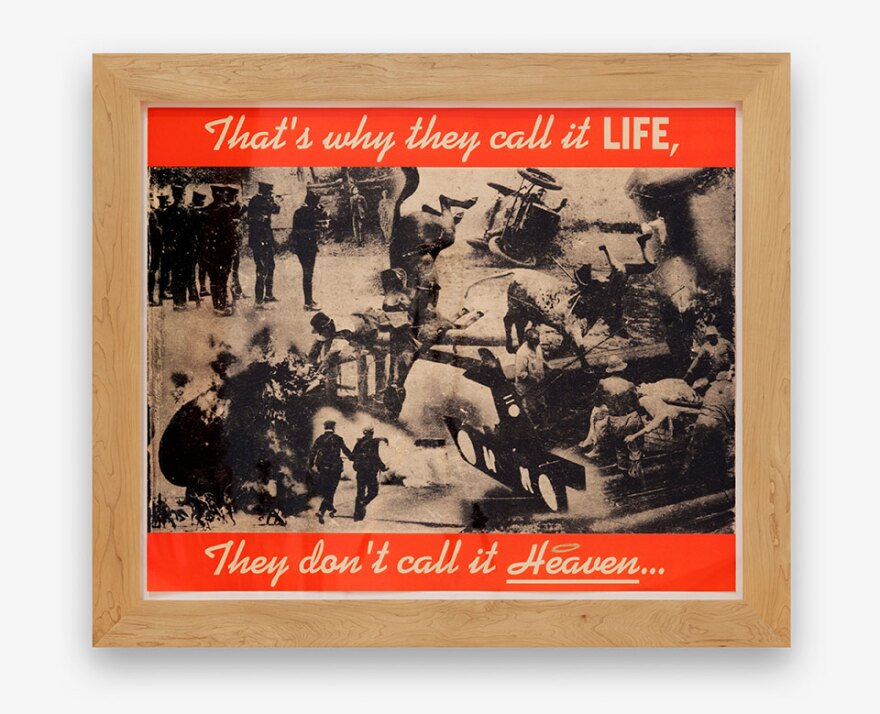

“There’s a really strong interest in personas throughout her work, and the kind of crafting of self,” Graham told KPBS in 2022. “It’s one of the reasons that she’s really looking to these ideas of old Hollywood, this myth that the girl next door, the boy next door, could head west, arrive in Hollywood and make it on the silver screen and become a star. That becomes a really clear example for her of what she sees as a particularly American ethos of self-invention and self-reinvention.”

The exhibit was astonishing and critically acclaimed, while also being a joy to browse with or without a critical eye. Smith’s work is delightful, thought-provoking and intensely observant.

“She taps something familiar in us — we respond to it, and then we somehow personalize it.”

— Kathryn Kanjo, MCASD

“She taps something familiar in us — we respond to it, and then we somehow personalize it. I think that she opens these things up to our own interpretation. She’s not giving us one straight answer, but she’s giving us a space to step in and ask our own questions,” Kanjo said.

In addition to the the works at UC San Diego, MCASD has nearly a dozen of Smith’s artworks in its permanent collection — and two currently on view: “Niagara,” a now-unsettling concrete tombstone in the sculpture garden, and “Montage of Disasters,” a collage piece.

“Alexis was courageous and she had this extraordinary tenacity,” Gregoire said. “She was completely an original. She didn’t fit into any particular ‘isms’ or art-historical easy explanations. She was completely herself. She was completely of this place, of Southern California.”