5 Art Movements that Influenced Architecture

As far as history goes back, art and architecture have always been interrelated disciplines. From the elaboration of the Baroque movement to the geometric framework of modernism, architects found inspiration from stylistic approaches, techniques, and concepts of historic art movements, and translated them into large-scale habitable structures. In this article, we explore 5 of many art movements that paved the way for modern-day architecture, looking into how architects borrowed from their characteristics and approaches to design to create their very own architectural compositions.

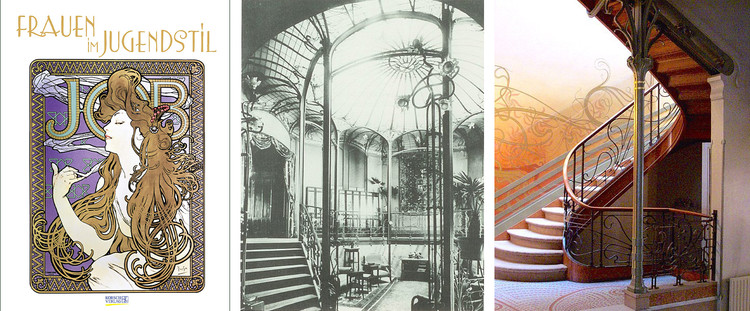

Jugendstil

Art historians have conflicting stories of who was the founder of the Jugendstil movement. It is believed by some that during the late-19th-early-20th century, Swiss artist Hermann Obrist launched the Jugendstil art movement in Munich, taking inspiration from the German art magazine Die Jugend (German for the youth). Although the artist initially studied botany and history, it was his trips to the countryside and his intricate observations of the organic forms and movements of nature that led to the creation of the style. Other historians explain that it was in fact a group of visual artists, namely Georg Hirth, Peter Behrens, and Otto Eckmann to name a few, who inaugurated Jugend in 1896 as a means of rebelling against the neo-classicism of art and architecture institutions. Prominent characteristics of Jugendstil included floral motifs, organically-shaped lines, flora and fauna, landscapes, and most importantly, the harmonious relationship between humans and nature. These features were translated into architecture and furniture design as Art Nouveau, an international movement that highlighted organic lines, nature-inspired motifs, movement, and use of both engineered and natural materials. Some of the first Art Nouveau houses were built in Brussels by Paul Hankar and Victor Horta, and featured elaborate motifs and intricate craftsmanship, blurring the lines between architecture and nature.

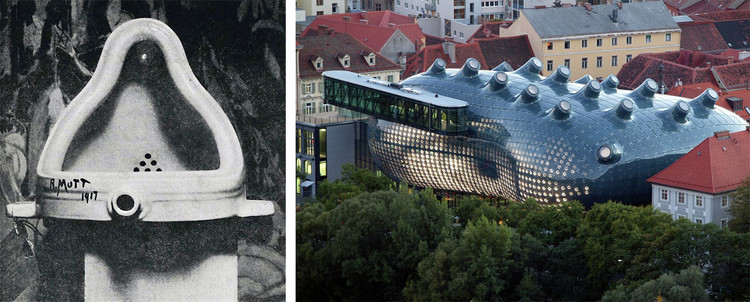

Dadaism

Considered a “rebellious and revolutionary” art movement in the early twentieth century, Dada art is said to have been first created at an artistic nightclub in Zurich, Switzerland called ‘Cabaret Voltaire’ after many war-opposing creatives sought refuge in the country. The movement gained momentum from 1916-1924 mainly in Switzerland, Paris, and New York, and featured works by notable artists like Hugo Ball (the founder of the movement), Marcel Duchamp, Hans Arp, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, to name a few. The radical avant-garde artists wanted to ridicule war and capitalist culture, so they resorted to irrational concepts of art that showcased humor, and the questioning of authority and reality through an “anti-art” approach.

This experimentation inspired architects like Otto Wagner, Erich Mendelsohn, and Adolf Loos to rethink ornamentation, form, and materials, and create buildings that were entirely different from what was being built at that time. The Glass Pavilion in Cologne, Germany by Bruno Taut, for instance, broke the norm of architecture and design and was the first of its kind to utilize concrete with a prominent geometric glass dome. Kurt Schwitters, architect-turned-graphic designer became known for his avant-gardist installations that he created in his own home, altering the concept of domestic space into something entirely different and unorthodox. Dadaism paved the way for many architects to rethink “traditional architecture” and was one of the first that inspired architects to look beyond architecture and see buildings as sculptures, launching movements like deconstructivism, one of the most controversial architecture styles of the 21st century that features projects by Daniel Libeskind, Frank Gehry, and Peter Cook, amongst many other big names in the field.

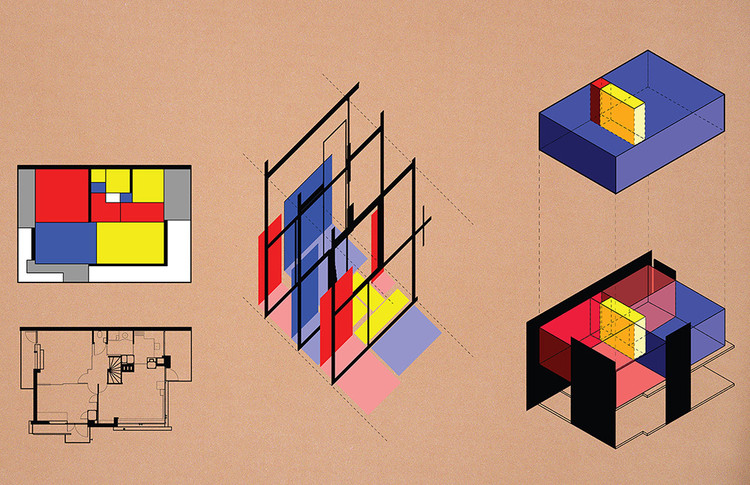

De Stijl

“We speak of concrete and not abstract painting because nothing is more concrete, more real than a color, a line, and a surface” – Theo van Doesburg. In 1917, the Netherlands-based De Stijl movement, led by the painters Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian, wanted to highlight the ideal fusion of form and function. Just like Dadaism, the movement was also a response to the chaos of World War I, so they created a visual language that consisted of refined geometric forms (often rectangles, squares, and straight lines) and primary colors. Many believe that the movement and its principles also stood against the visual garishness of Art Deco and found an indirect inspiration from Cubism. De Stijl’s influence on the field of architecture helped inspire the launch of the International Style of the 1920s and 1930s, also referred to as Modernism. De Stijl’s use of essential forms and colors with simple horizontal and vertical elements, as seen in projects like the Rietveld Schroder House by Gerrit Rietveld and Café l’Aubette by Theo van Doesburg, allowed for flexibility and transformation of space, meaning that there were no hierarchical arrangements of rooms in floor plans, just independent planes that compose spaces based on the user’s functions and needs. The structural composition of the Schroder House has been the subject of study by many architects, artists, and historians.

Pop Art

The Pop Art movement introduced an entirely new approach to design, drawing inspiration from media, mass production, and pop culture. The movement first appeared in the United Kingdom in the 1950s when the economic and social conditions post WWII led artists to celebrate mundane, everyday objects and transform them into fine art. Soon enough, American artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein joined in on the movement and became pioneers in it, replacing historic art with a vibrant mass-produced, and media-oriented visual realm. In terms of architecture, the movement inspired architects to liberate themselves from the linearity and modesty of modernism and opt for structures that defy what was considered “normal” back then. Similar to the approach in art, mass production, and commercialism were front and center in architecture, pushing forward the use of technology, signalism, and mass consumption. Facades, interior spaces, and public realms became canvases for experimentation with light, color, irregular forms, and unconventional scales.

Surrealism

As explained by the name itself, surrealism explored visual art and literature as a means to “revolutionize human experience” through unconventional imagery. Coined by French avant-garde poet Guillaume Apollinaire between World Wars I and II, surrealist art became a movement that promotes the liberation of the mind and artist’s expression, creating what they depict as alternate realities and exploration of the psyche. Surrealist techniques and features included distorted scales and perspectives, unconventional materials, and collective compositions and layering. Since its rise to popularity, artists like Salvador Dali and Frederick Kiesler have profoundly shaped the architecture of the 20th and 21st centuries. Whether it’s through interiors that represent literal symbolic imagery, the use of trompe l’oeil techniques to create an illusion, Austrian-American architect Frederick Kiesler’s iconic Endless House, or Frank Gehry’s Vitra Design Museum, the movement produced radical concepts of what architecture could be defined as.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on December 01, 2021.