Art

Julia Fiore

The European Fine Art Fair, better known as TEFAF, anchors the social calendar for any serious collector of antiquity, Old Master works, or fine jewelry (read: anyone serious about the finer things in life). The annual fair, open to the public March 16th through 24th, takes place in the MECC Maastricht, a conference center in the eponymous sleepy Netherlandish college town, and gathers 279 international dealers of art and antiques from around 21 countries. Now in its 32nd edition, TEFAF Maastricht expanded its modern and contemporary section, a shift in focus that speaks to the rapidly aging collector base it has relied on for so long. It might have been nice to see dealers teasing out the connections between modern, historical, and ancient artworks, but as in most fairs, each dealer is out for himself in the high-stakes sales environment. Still, I can’t complain—the pleasure of TEFAF lies in the many opportunities to view spectacular artworks and objects of all kinds that frequently live in private collections beyond public view.

Queen Josefina of Sweden’s natural pearl and diamond necklace

Symbolic & Chase, London

Booth 247

Queen Josefina of Sweden’s natural pearl and diamond necklace. Courtesy of Symbolic & Chase, London.

The exceptional and aspirational jewelry presented at TEFAF makes one wonder if there are events grand enough today to merit such overindulgent showpieces. Still, a girl can dream, and Bond Street dealer Symbolic & Chase’s natural pearl–and–diamond necklace from the collection of Joséphine de Beauharnais, the 19th-century queen of Sweden and Norway, conjures immodest princess fantasies. For various environmental reasons, the gigantic, teardrop-shaped natural pearls that hang from the double strand of round gems can no longer be produced today. Their size and luster certainly befits their royal heritage, and the piece features in several of Josefina’s official portraits. The accessory reinforces her power and youthful beauty, but “besides being immensely becoming to her looks,” art historian Diana Scarisbrick wrote for Sotheby’s in 2014, “the effect of this iridescence, while quite different from the brilliance of transparent stones, was also majestically imposing and transformed Josefina’s appearance from that of a mere mortal into that of a Queen.” If diamonds are more your thing, the dealer also has a whopping 114-karat yellow diamond necklace accompanied by Colombian emeralds and, yes, more pearls, designed by JAR.

Barry X Ball, Sleeping Hermaphrodite (2008–17)

Fergus McCaffrey, New York, Tokyo, and St. Barth

Booth 440

Barry X Ball, Sleeping Hermaphrodite, 2008–17. Courtesy of Fergus McCaffrey, New York, Tokyo, and St. Barth.

The undeniable hit of the fair (at least based on the hordes of photo takers)—and a much-needed shot of grandeur for the modern and contemporary section—is Barry X Ball’s “Masterpieces” series, robot-generated recreations of iconic sculptures from the annals of art history, presented by Fergus McCaffrey. Ball’s version of the Louvre’s famous Hellenistic sculpture, Sleeping Hermaphrodite (ca. 3rd–1st centuries B.C.E.), appears in translucent pink Iranian onyx, a fitting millennial-pink homage to a sensual icon of intersex identity. Last year, Artsy named Ball one of seven artists “smashing our expectations of what marble can be,” an honorific confirmed by his utterly 21st-century approach to traditional works of art. After taking hundreds of images of the original sculpture, Ball creates a 3D scan, uses a CNC milling technique to carve the stone, and then polishes it by hand. This might at first seem like a cheap trick (if hand-carving was good enough for Michelangelo), but Ball’s methods reject high-brow notions of originality and authenticity, and—perhaps to the chagrin of some historians—attempt to improve upon or “perfect” what many would consider already-perfect masterpieces. The striking Hermaphrodite is on loan from the artist, but two busts nearby—Envy (2008–19) and Purity (2008–18)—are available for $425,000 apiece.

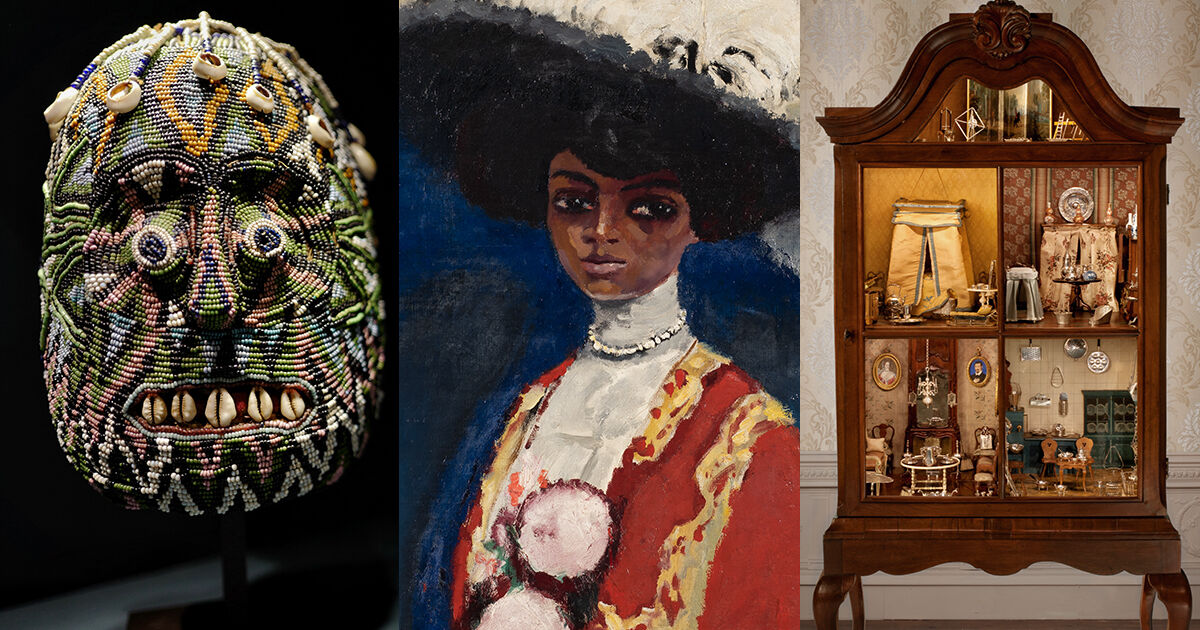

Atwonzen, or Magnificient Beaded Head, from the Dschang Region, Cameroon (ca. 1700–1800)

Martin Doustar, Brussels

Booth SC 4

Atwonzen, or Magnificient Beaded Head, Dschang Region, Cameroon, c. 1700–1800.

The Brussels-based art dealer Martin Doustar, who specializes in ancient and primitive works, presents a selection of rare and spectacularly colorful artifacts. This beaded head from Cameroon is one of only seven known atwonzens from the Bamileke culture (one is in the collection of the De Menil Foundation, another is in the Musée du Quai Branly, and the rest are in private hands). Bill Ziff, the prominent 20th-century collector of primitive art, was the owner of this finely wrought piece, composed of glass beads and cowry shells. The complexity of the beadwork and its “striking expression of death,” Pierre Harter writes in his 1986 volume, Arts Anciens du Cameroun, make this mask a particularly fine example of the genre. And it has a price tag to match: €160,000, or a little more than $180,000. Prized tokens of power, such pieces were carefully constructed by the best royal artisans to be worn by chieftains on their belts; the care with which the mask was stored has left it remarkably preserved.

Kees van Dongen, Plumes blanches (1910–12)

Dickinson, London and New York

Booth 402

Kees van Dongen

Plumes blanches, 1910-1912

DICKINSON

Throughout the fair, I found the society women populating Kees van Dongen’s portraits staring out at me from their muddy canvases. The smattering of works by the French-Dutch painter on view at various gallery booths seems to foretell a coming moment for an artist frequently overshadowed by Fauvist and Die Brücke peers such as Henri Matisse and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. The two lovely Van Dongen paintings in Dickinson’s presentation are homages to the female form. Nu fauve a la jarretière rouge (1905–07) shows a pretty, if somewhat predictable, odalisque rendered in broad green-and-pink brushstrokes. It’s the unknown woman in Plumes blanches (1910–12), however, that captures Van Dongen’s knack for decidedly modern, emotionally complex portraits of upper-class women. The dealer could not confirm the identity of the sitter, who looks out at the viewer almost confrontationally, her exceptionally plumed hat adding to her regality. Yet her dark skin suggests that she may be of North African descent, a hypothesis supported by the recent trip the artist had taken to Algeria. Nevertheless, she is a showstopper; her mysterious air and dramatic accessories can be yours for $6.5 million.

Wall Hanging (ca. 1st half of the 18th century), probably Mexico

Eguiguren Arte de Hispanoamérica, Buenos Aires

Booth 153

At the very back of the Latin American art dealer Eguiguren’s booth, which prominently features antique silver, is an intricately embroidered wall hanging of astonishing quality. The background, composed entirely of flattened silver wire coiled around silk thread, lends it a rich opulence, which wonderfully reflects light. The painterly, decorative elements of the work—Rococo symmetry and flower motifs inspired by Indian chintzes, textiles then heavily imported into Europe—speak to a global colonial history marked by the craze for ornate splendors. A coat of arms surmounted by an open crown and mitre in the work’s center suggests that the costly commission was for a high-ranking bishop. Eguiguren originally dated the wall hanging to the late 18th century, but TEFAF officials believe it hails from the first half of the century, a correction that makes the beautiful condition of the piece even more worthy of its €300,000 (about $340,000) valuation.

Cradle (1907–08), designed by Josef Hoffmann and executed by J. & J. Kohn

bel etage, Vienna

Booth 606

Moms of a certain social standing know that we live in an era in which discreet wealth is the new status symbol, a trend encapsulated by the inexplicably expensive clogs that have quickly become part of the official uniform of a subset of Brooklyn mothers. It’s to this group that I recommend Josef Hoffmann’s deceptively simple, wonderfully balanced cradle on offer from Vienna-based gallery bel etage. For a cool €130,000 (approximately $147,000), you can take home the fully functional and perfectly engineered bent beechwood crib by the influential avant-garde designer. In keeping with the ethos of the Vienna Secession and Wiener Werkstätte, groups dedicated to elevating the designs of useful, everyday objects, many of Hoffmann’s furniture and applied arts have been widely copied and distributed. Yet this piece, a rare example of his work for children, won’t appear in the houses of jealous friends: Only one other iteration of the cradle is known, and it lives in permanent stasis at the Berlin Bröhan Museum (that model, however, lacks this one’s charming curtain fixture).

The Anna Maria Trip Dolls’ House (ca. 1750–60)

John Endlich Antiquairs, Haarlem

Booth 235

The voyeuristic pleasure of dollhouses and the confused disbelief of seeing finely rendered objects in a miniature scale commingle in Anna Maria Trip’s sumptuous model from the mid-18th century. The fully furnished three-story house offers a revealing glimpse into the world—and worldly possessions—of the well-to-do in the Netherlands during a time of extreme luxury and social ambition. Splendid dollhouses such as this one were not meant for children to play with; they were instead displayed as wünderkammer to entertain visitors and to show off their owners’ excellent taste. Here, the elegantly appointed rooms sport the chic chinoiserie styles popular at the time, and are decorated with silk-upholstered furniture, real miniature paintings in gilt-bronze frames, and an unusually large collection of objects executed in silver. In an age of short attention spans, a doll house as intricate as this one invites and rewards prolonged looking. The dealer said that a foundation purchased the work, and it will be on display in a Dutch museum.

JF