Artist Jyoti Bhatt was only 12 when one of his earliest paintings signalled the course his expansive artistic career would take. Titled “Chheta R’ejo Maa Baap” (Please keep distance sir), the watercolour depicted a Dalit carrying human waste on his head and a broom in his hand, walking down the street yelling, so that the upper castes were informed of his arrival and kept their distance. Exhibited at his school in Bhavnagar, it evoked complaints from parents but Bhatt’s art teacher Jagubhai Shah told them that artists must have freedom of expression. “I was exposed to the caste system and had developed a dislike for it because I was inspired by my (freedom fighter and educationist) father’s way of thinking and behaving,” says Bhatt, adding, “This was in 1946, when Gandhiji was understood better than he is today.”

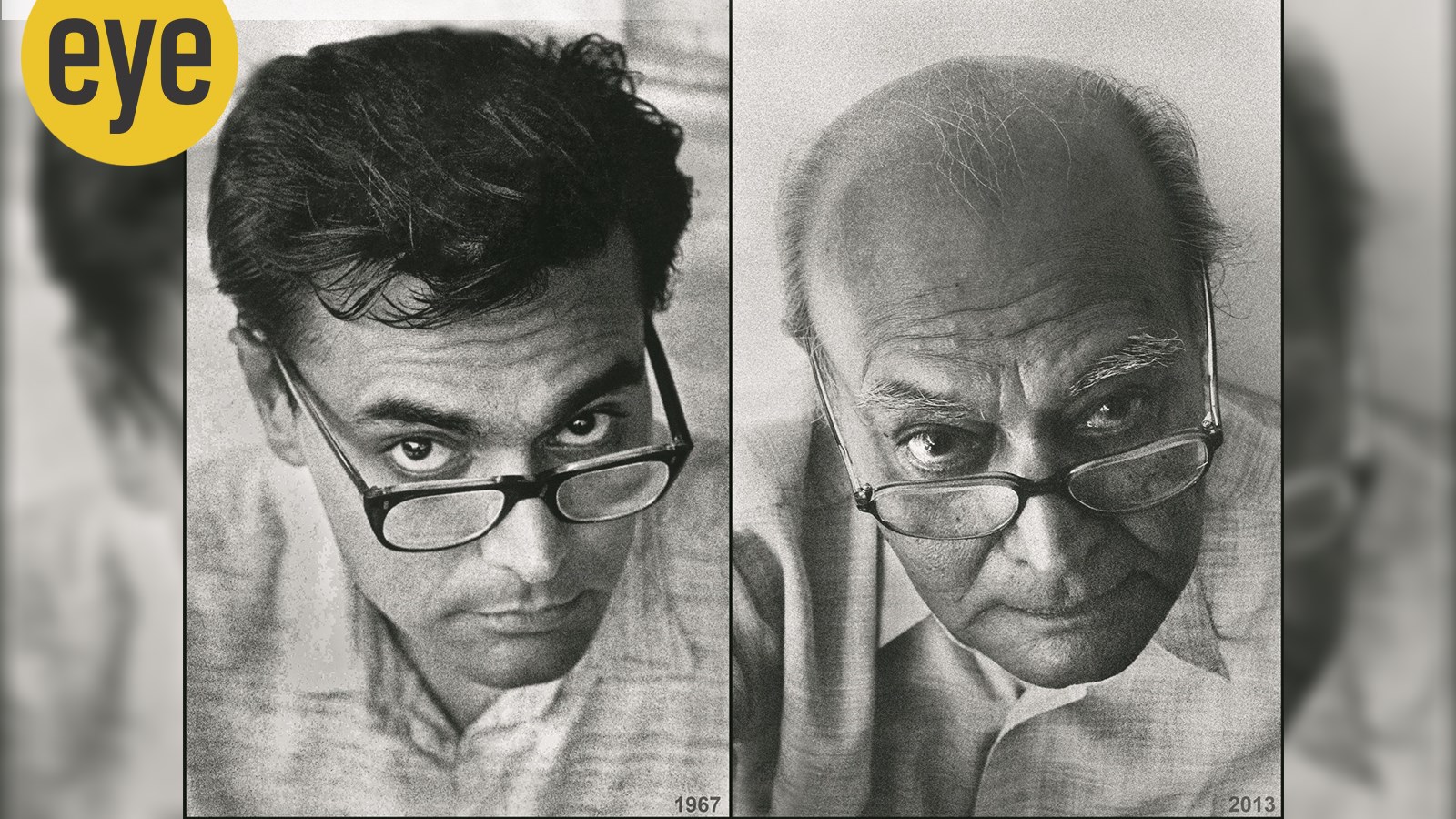

Years later, he continues to impart those lessons to the steady stream of young artists who turn up at his house in Vadodara. Less than five kilometres from the Faculty of Fine Arts (FoFA) at Maharaja Sayajirao University (MSU), where he spent decades — first as a student, then a teacher — Bhatt is grateful for their support. “I am fortunate that there are a large number of younger artists in Baroda who continue to visit me, mainly to help solve my technical problems, which I am unable to do myself due to my health condition,” notes the artist-educator. Several of them have also planned a celebration on March 12, when the noted artist turns 90.

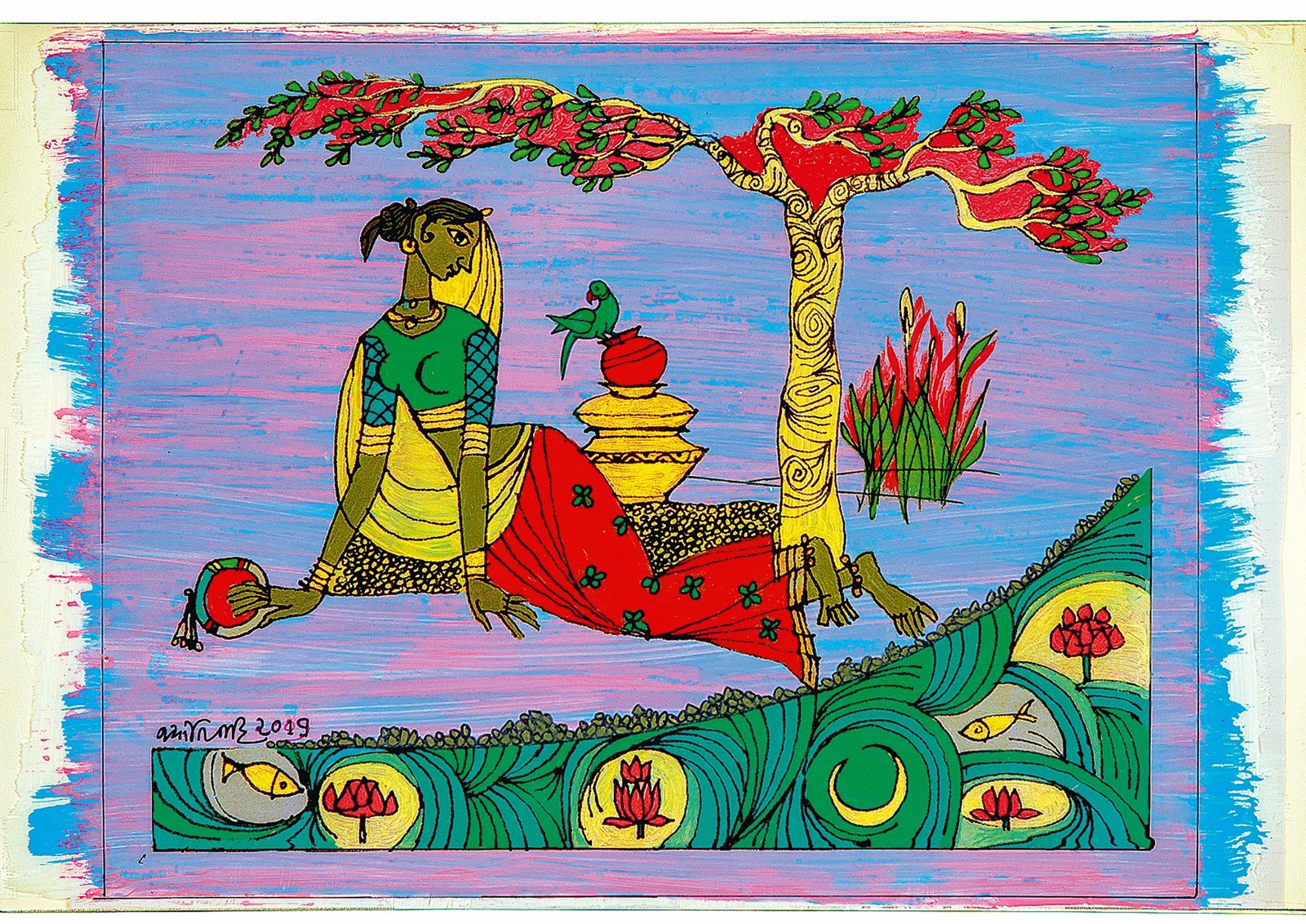

A pioneering photographer who documented the indigenous traditions of rural India and is recognised for his modernist engagements in printmaking, the 2019 Padma Shri awardee — whose works are in prestigious collections, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, and British Museum in London — is also presenting a solo of his paintings after 60 years at Delhi’s Vadehra Art Gallery. Titled “Revisitations: Engaging the Archive”, the show closes on March14. Comprising over 80 works, spanning over two decades, the reverse paintings rendered in acrylic on plastic film, feature his inquiries into iconography, portraiture, rural life, still live, and the natural world. “I call this my ‘Golden Period’. I have used gold paint in most of these current paintings,” he says.

****

Born in 1934 in an India fighting for Independence, Bhatt inherited from his father, Manshankar Bhatt, a desire to see a nation on the road to progress. Noticing his passion for drawing and painting as a child, his teachers at Gharshala trained him and he found mentors in artists such as Somalal Shah and Jagubhai. An ardent reader of artist and writer Ravishankar Raval’s Gujarati literary magazine Kumar, he studied the works of numerous artists, including stalwarts NS Bendre and KG Subramanyan, who were to become his teachers at MSU when he enrolled there as part of the first batch of students in 1950. “All these teachers considered themselves our parents… Though our curriculum was not much different from the one followed by other art schools, except Santiniketan, prominence was given to experimentation and creativity. Apart from this, equal importance was given to extracurricular learning. We were fortunate that a vast public garden, including a zoo and a large museum, were just across the road and we were encouraged to spend as much time there as we could,” recalls Bhatt. With students from across the country, FoFA was a melting pot where young artists were encouraged to develop individual aesthetics. Bhatt recalls his own experiments with charcoal, pastels, oil colours and watercolours. Assisting Subramanyan on a mural, he learnt the encaustic technique, where beeswax was mixed with ingredients such as resin and turpentine to produce colourless and translucent material that could be mixed with oil colours that were more expensive in comparison.

By the time he travelled to Naples in 1961-62 to study at the Accademia Di Belle Arti on a scholarship from the Italian government, he was already a faculty member at MSU and an artist of repute, who had received formal training in mural and fresco painting at Banasthali Vidyapith in Rajasthan. He had won the 1956 President’s Gold Plaque at the National Exhibition of Art in Delhi.

In a Europe rebuilding itself in the aftermath of World War II, Bhatt was captivated by its art and architecture, and the heavily textured and layered canvases of artists such as Antoni Tàpies and Alberto Burri. This is also where he made his first etching and an intaglio print from a collagraph plate. As new materials like sand, jute cloth, iron pieces, brass sheets, plywood, tapes, stone pebbles and linoleum entered his vocabulary, he produced works such as Burnt Place (1962), using oil, sand and iron pieces to raise the surface, and burnt the gunny surface to create holes. Several of his friends recall how on his return to India, he lugged back enormous amounts of white glue that he had found to be useful; unaware that the similar Fevicol was now available in the domestic market.

Credited later with introducing the intricacies of the intaglio process to several of his contemporaries, there was still time before Bhatt could create an etching at MSU, where the etching press required repairing. “As a part of the press was damaged during transportation, we were not able to use it for 16 years, till 1966, due to bureaucratic rules,” recalls Bhatt. Though a postgraduate course in printmaking was introduced at the institute in 1968, and artists such as Jeram Patel and Bhupen Khakar had also started making etchings, finding the right tools, ink and paper remained a challenge. Bhatt’s own expertise in the medium, though, was honed during a two-year Fulbright scholarship to study printmaking at the Pratt Institute and Pratt Graphic Art Center in New York (1964-66). The period saw him produce mixed intaglios such as the abstract Metaphysical Landscape (1964/68) and Forgotten Monument (1964/68). Textual references entered works such as A Face (1972) and Pseudo Tantric Self Portrait (1969). In Kalpavruksha (1972) the woman’s eyebrows took the form of dhanushya (bow) and formed part of a mythical tree. The self, too, came to the fore in works such as Self Portrait in New York (1964) and Man Under the Sky (1965).

*****

While the image and the possibilities of its myriad meanings remained central to his oeuvre across all mediums he pursued, a 1957 travelling exhibition curated by Luxembourgish-American photographer Edward Steichen, and brought to Ahmedabad by MoMA, convinced him about the communicative power of photography. When a seminar on Gujarati folk art at Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan in Mumbai was announced to take place in 1967, armed with a Canon SLR analogue camera, and accompanied by artist-friends Gulammohammed Sheikh and Khakhar, Bhatt set out to document the visual culture of Gujarat, transversing the tribal areas of south Gujarat, spending hours on the road, taking trains, buses and walking miles to reach uncharted territories. The realisation that the native art traditions of India were dying and there was a need to document them also led to journeys across Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and the four erstwhile states of south India. He also travelled to areas in Punjab, Jammu, Ladakh, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Andaman Nicobar Islands, making his last visit for the purpose of documentation to Odisha in 1994. “Art and culture could not be seen exclusive of people but formed inseparable parts of their lives,” notes Bhatt.

Embodying pictorial values of rural arts interspersed with art historical references, his images are testament to the lived past and an archival record that documents, among others, beliefs and religious practices, stone carvings and shrines, wall paintings and intricate embroideries. Their reflections are also evident in Bhatt’s paintings and prints that incorporate symbols of the indigenous past he witnessed. If the Kalpavruksha series, for instance, embodies the principle of purush–prakruti (man-nature), in the iconic 2005 acrylic A-B-Zee of My India, he interspersed recurring motifs, from parrots and peacocks to nag devta, with words and phrases in English and Gujarati that bring together India. “In every aspect, he was ahead of his times. In his art, he was doing certain things way before notions of post-modernism were enquired. Within the framework of eclecticism, this was a man who was looking at how language constructs could marry themselves in extremely different ways. Disregarding neither traditional spaces nor the ideas of change that occur because of events in history or technology, he was always curious about things. So, his preservation through photography of things that were being lost was not in the notion of a conservative idea of holding on to a past, but looking at something that needs to be remembered and ‘archived’ way before the ideas of archiving came into existence,” says artist Rekha Rodwittiya, who was his student at FoFA from 1976 to 82. She remembers his ‘feminist politics’ and how he wanted his students to grow beyond him. “He never imposed linguistic preferences as a teacher. Someone who understood the value of investigation, research and collaborations, he encouraged these kinds of premises,” she adds.

Along the way, numerous biases within arts were also addressed. “As it has been in our caste system, there is a parallel hierarchical classification followed among most of those related to the art world in India. Thus, a photograph is considered inferior to a ‘graphic print’. And, the print, in turn, is given a lower place than a painting, by both art galleries as well as art collectors. As if this is not erroneous enough, there are sub-castes also,” he stated in an essay written for the catalogue of his 2019 solo in Vadodara.

Bhatt continues to learn and discover. “He is someone who insists of himself that the practice of art is like an everyday riyaaz,” says Rodwittiya. So new meanings are being unearthed as he browses through ‘sketchbooks’ he has been maintaining since his student days, when he recalls completing at least 30 sketches daily, from his surroundings and portraits of his co-students, for Bendre’s assessment. There are also diaries scribbled with notes detailing his observations during his travels. “After a few years, I started adding sketches of my ideas, adding written notes about colours, materials and methods that could be used to make a painting,” notes Bhatt. He has also turned to some of these for the ongoing exhibition in Delhi. “The sketchbooks became a kind of time machine that took me back to the days when those sketches were made, and I realised that I have started enjoying remembering those early days. So, I decided to start working on those old sketches without or with as little changes as possible, adding necessary details and colours the way I might have done during the days when the sketches were actually made. My intention to do this decided the final form of these paintings,” he adds.