At the height of the 1960s and 1970s Black Arts Movement, Black American artists utilized their work and established community-oriented cultural spaces to reclaim agency. They recognized and promoted the power of art for social change and self-empowerment, expressing the nuance of Blackness on their own terms. The emergence of grassroots institutions like the Langston Hughes Center for the Visual and Performing Arts in Buffalo, New York, which opened in 1971 and continues to be a resource for cultural knowledge, speaks to how local artists fostered this collective mobilization. I am interested in how examining legacies like these through my curatorial work can significantly expand our thinking about the expression of Black identity and the relationships between fine art, community, and everyday life.

Buffalo is often under-recognized for its enduring history of artists, change-makers, and arts advocates whose work expresses the breadth of Black culture and encourages folks to consider their own complexities. This exhibition aims to celebrate the multigenerational legacy of Black arts in Buffalo as it connects to broader conversations around representation, identity, and freedom of expression. The featured artists are just a small representation of a robust cultural landscape that thrives on community; their work speaks to the histories, spaces, and concepts that bridge us together across time, place, and media.

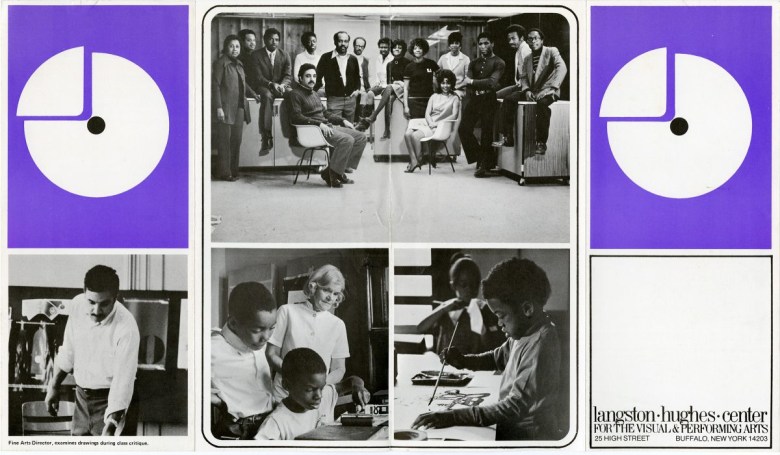

Seeing ourselves reflected in history encourages us to forge our own pathways and make our own mark. Visitors of all ages at the Langston Hughes Center were able to learn from and connect with a range of local working artists as they delved into their artistic sides, pictured in the center’s archival leaflet. Having space to think about the function of art in our lives is vital. Scholar bell hooks argues that for Black communities to reconnect with visual art as a liberatory tool, increased exposure to a diverse range of Black artists must be prioritized alongside free creative expression for the masses. In Art on my Mind, she writes, “If black folks are collectively to affirm our subjectivity in resistance, as we struggle against forces of domination and move toward the invention of the decolonized self, we must set our imaginations free. Acknowledging that we have been and are colonized both in our minds and in our imaginations, we begin to understand the need for promoting and celebrating creative expression.”

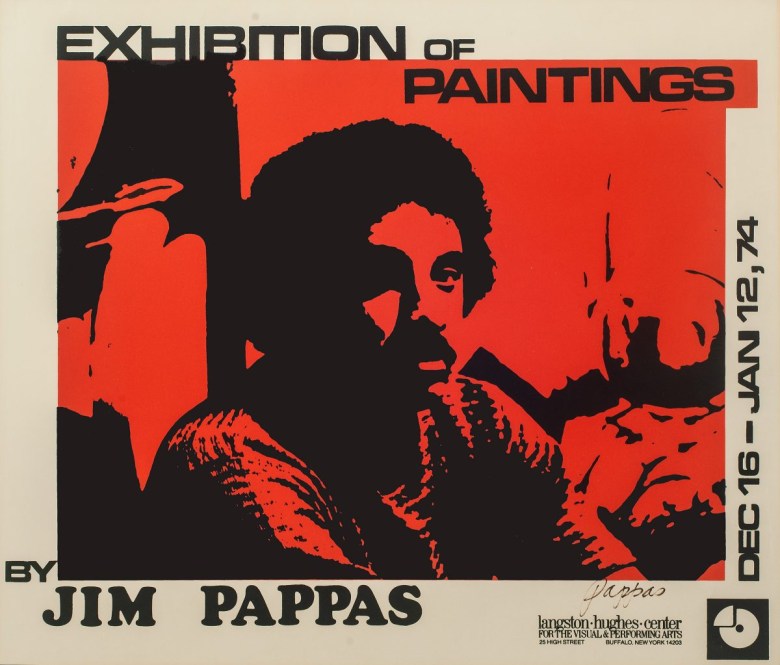

Cultural spaces like the center celebrated experimentation by encouraging students to explore new media. It also introduced the public to local and national Black artists and served as a working space for its teaching artists to develop their practices. Widely recognized as an Abstract Expressionist painter, co-founder James Pappas’s multidisciplinary practice also includes screen printing and photography. The black and red screenprint for his 1974 solo painting exhibition centers Pappas as the artist and subject in its production and composition, departing from the abstraction seen in most of his paintings and other screen prints. By creating an aesthetic object to promote his own exhibition, the work communicates his many layers. It radically blurs the boundaries between artistic and curatorial practice to emphasize his interconnected roles as a multidisciplinary artist, arts administrator, and curator.

Contemporary portrait artist Julia Bottoms similarly brings out the nuances of her subjects, particularly in her self-portrait as an artist and a mother in “My Mother’s Crown.” The painting depicts her cradling her son in a loving embrace. Wrapped in a cloth sheet, her soft gaze meets the viewer’s eye in an unflinching moment of both vulnerability and power. She expresses total acceptance of herself, posing without makeup to acknowledge the minor imperfections that are true to who she is. Highlighting herself as a mother within a series inspired by religious iconography and Victorian-era portraiture, she affirms the significance of both of her roles and how they nurture each other. The image resists the notion that women, and Black women in particular, must choose between career and family. It also affirms Black motherhood as beautiful and worthy of celebration.

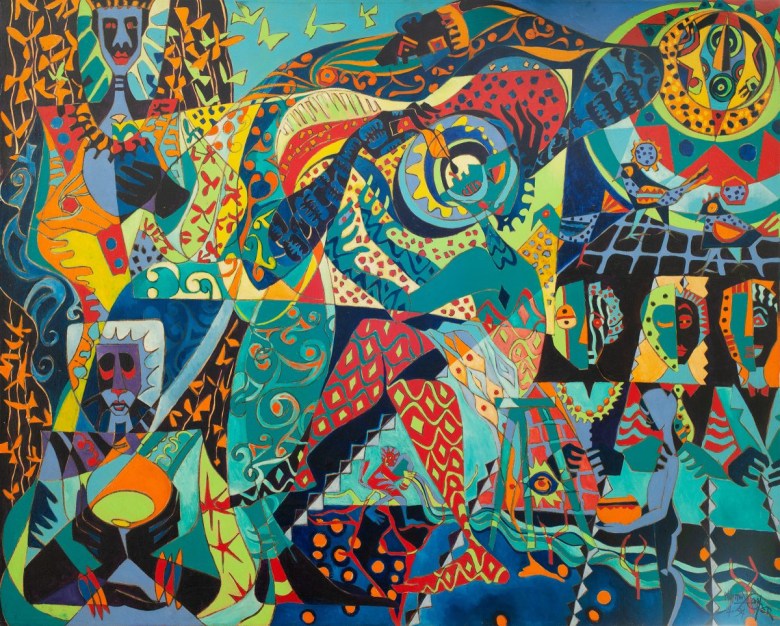

The freedom to put forth the multitudes of our identities is a theme explored by several local artists I’ve come to know and work with. Internationally acclaimed artist LeRoi Johnson utilizes bold, bright colors as well as African, Caribbean, and South American cultural influences to depict dreams and visions roused by personal experiences. Heavily inspired by the music and culture of Brazil, his narrative work engages with identity and social justice. Works like “The Conversation”incorporate recurring circular motifs and colorful figures to depict a communal gathering within a lush, otherworldly landscape. The artist’s use of vibrant colors speaks to the layers that color our identities and the fusion of cultures, histories, and influences across the African diaspora. The conversation portrayed reflects the fluidity between the local and the global, the past and the present.

A painter, muralist, author, and educator, the late William Y. Cooper similarly used a vibrant palette to explore his own ancestral legacy. The 1994 painting “Naming Ceremony, Ghana” represents the life-changing moment when the artist received his African name during a special ceremony in Ghana. The Afrocentric aesthetic in his drawings and paintings celebrates his African heritage alongside his American identity. This was a central element to Cooper’s artistic practice and community engagements; he founded the Afrocentric Artists’ Collective and ran the organization from 1979 to 1981. One of Pappas’s contemporaries, Cooper similarly drew inspiration from jazz music. His rhythmic compositions emanate a sense of harmony that invites the viewer to take time and meditate on all the elements of his work.

Black artists have long fused music, visual, craft, and performing arts to create new modes of expression, constantly reinventing styles, genres, and techniques. This preserves a collective history and transcendent cultural tradition as it continues to evolve. Locally, Cooper’s and Pappas’s artworks exemplify the formative impact of jazz on the visual arts landscape. This continues with contemporary artists like Edreys Wajed, whose linear, graphic aesthetic and mark-making process visualizes some of his favorite hip-hop songs. His multidisciplinary creative practice embodies a seamless movement across disciplines, explored further in my previous article, Seeing Ourselves and Each Other in Buffalo’s Black Arts Scene.

Pappas’s high-contrast photographs, like “Dizzy Gillespie at the Tralf,” document jazz greats who have given legendary performances in Buffalo, deepening the interrelation of the local music and art scenes. Documentary and portrait photographer DJ Carr is building on this tradition, recording the contemporary kinship between fine art and hip-hop. Carr’s photography offers a raw and honest look at people, places, and moments he encounters in his community that are often overlooked. “Uptown Titans”portrays Billie Essco and Jae Skeese, two of the city’s prominent rap artists. Essco, who is also the visionary behind Cafe Czen, has an innovative practice that fuses hip-hop, fashion design, art history, and his love for his native Buffalo. His strides as an artist and designer build on the city’s artistic legacy that resists limitations on what is embraced as fine art. Like Carr’s photography, Essco’s work celebrates Black culture and Buffalo culture at its most authentic and demands its recognition in the mainstream art spaces from which it historically has been excluded.

Black artists, past and present, in Buffalo and beyond, have continued to assert the right to take up space. Emerging artist Bree Gilliam focuses primarily on social issues and daily experiences in her figurative art. The painting “There Goes the Neighborhood” (2023) depicts a young, Black family radiating with a playful sense of joy and togetherness. In contrast, the title alludes to the thinly veiled racism of redlining and white flight, responses to frequently perpetuated stereotypes that diversity in neighborhoods decreases property value or poses a threat to white residents. Despite this, the family stands firm, confident, and united in front of their home, resisting challenges to their right to be there.

As I think about the legacy I hope to create as a Black woman artist, writer, and curator, the blueprints laid before me remind me that there are no limits. I am inspired every day by the artists who surround me and the city that has embraced me. Our stories are forever intertwined, and we will continue to elevate our own voices, each other’s, and that of our community. It is my sincere hope that by doing so, our stories will be recognized within a broader legacy of Black art and culture, remembered, and celebrated for generations to come.

Editor’s Note: This online exhibition is part of the 2023/24 Emily Hall Tremaine Journalism Fellowship for Curators and follows two posts by the author.

Tiffany D. Gaines will discuss her work and research in an online event moderated by Editor-in-Chief Hrag Vartanian on Tuesday, March 19, 6pm (EDT). RSVP to attend.