With white hair and a white beard framed by spectacles and a cabbie hat, Vladimir Dikarev cuts a quiet figure. He leads me through his new exhibition, describing his work in Russian, his voice barely echoing in the cavernous former church that is the Museum of Russian Art in Minneapolis.

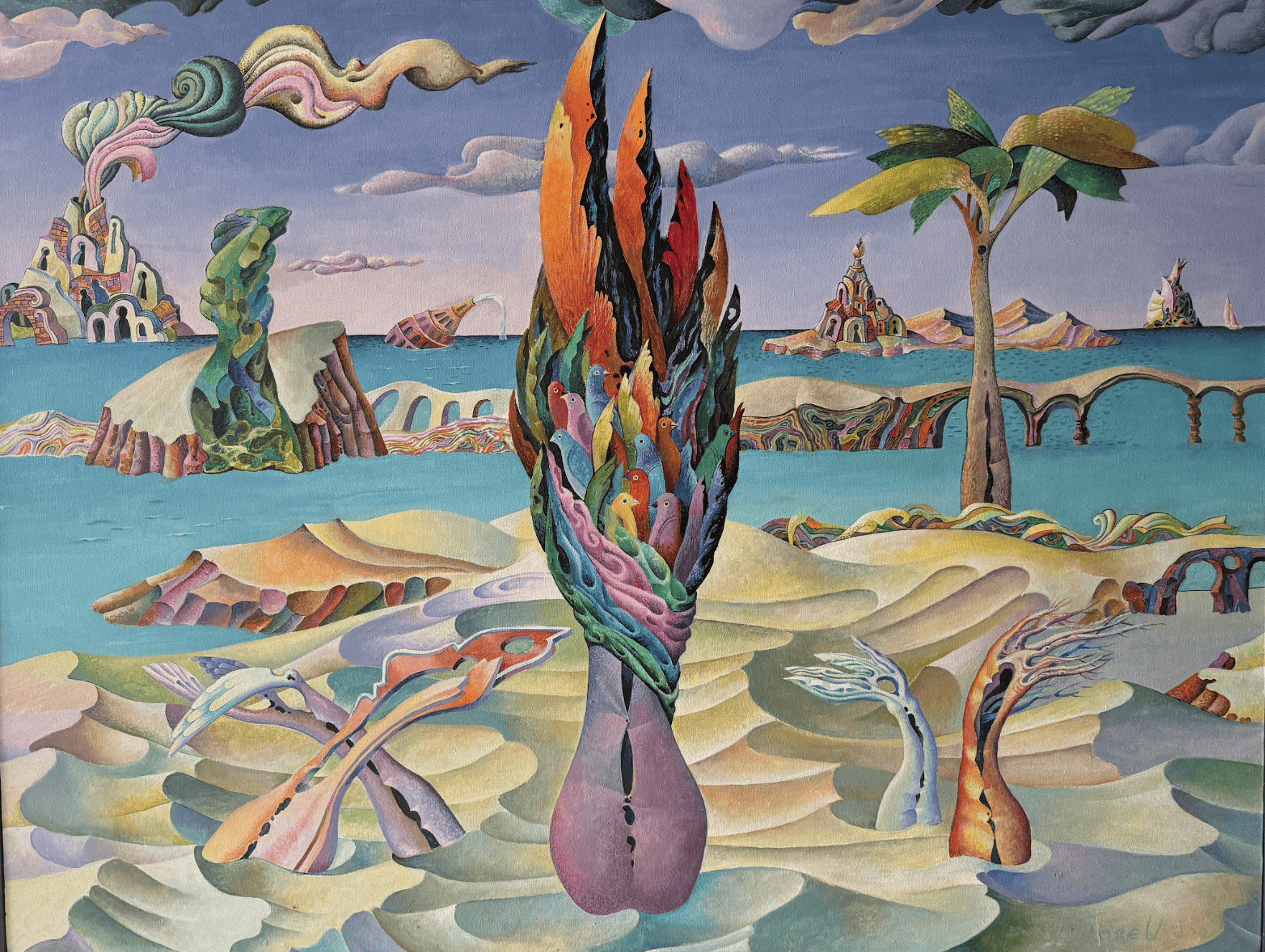

Dikarev walks amongst the world he’s created, hung on the walls around him, transforming them into landscapes of pulsating candy-colored dunes. His paintings are populated by curling clouds that ripple out into oblivion, and bearded men and angelic figures with clothing like sails whipping in an invisible storm.

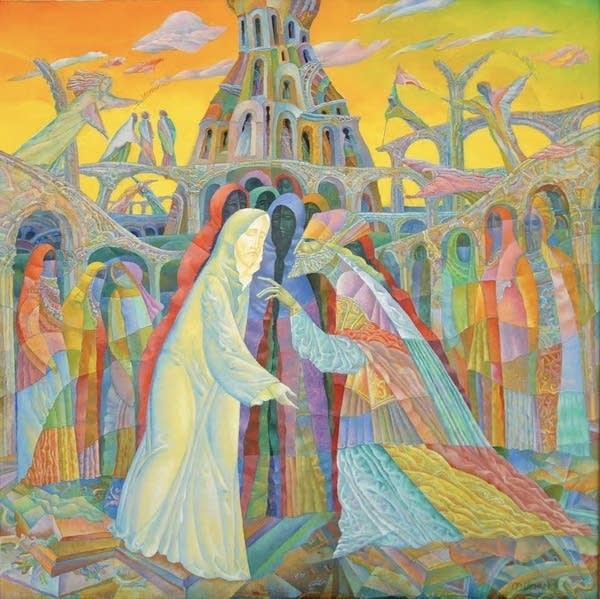

“Transfiguration,” 2000.

Courtesy of the Museum of Russian Art

Chief curator Maria Zavialova, walking alongside, tells me that Dikarev’s new exhibition, “Portal to the Surreal,” is in celebration of the 100th anniversary of Surrealism. (Reinforcing this dreamlike, fantastical sensibility is a show of surrealist sculptures on the first floor by Minneapolis-based Yugoslavian artist Zoran Mojsilov.)

One hundred years ago, the Surrealism movement was born when French critic André Breton published the “Surrealist Manifesto,” a call to suppress conscious thought in making art — and in life. Surrealists, like the more anarchic Dadaists, were grappling with the dust and horror that remained in the wake of World War I.

Your gift today creates a more connected Minnesota. MPR News is your trusted resource for election coverage, reporting and breaking news. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone – free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

To process and escape the absurdity of war, Surrealists tapped into the subconscious, channeling their dreams and subversive imaginations to create an alternate reality.

Dikarev is very similar to his predecessors.

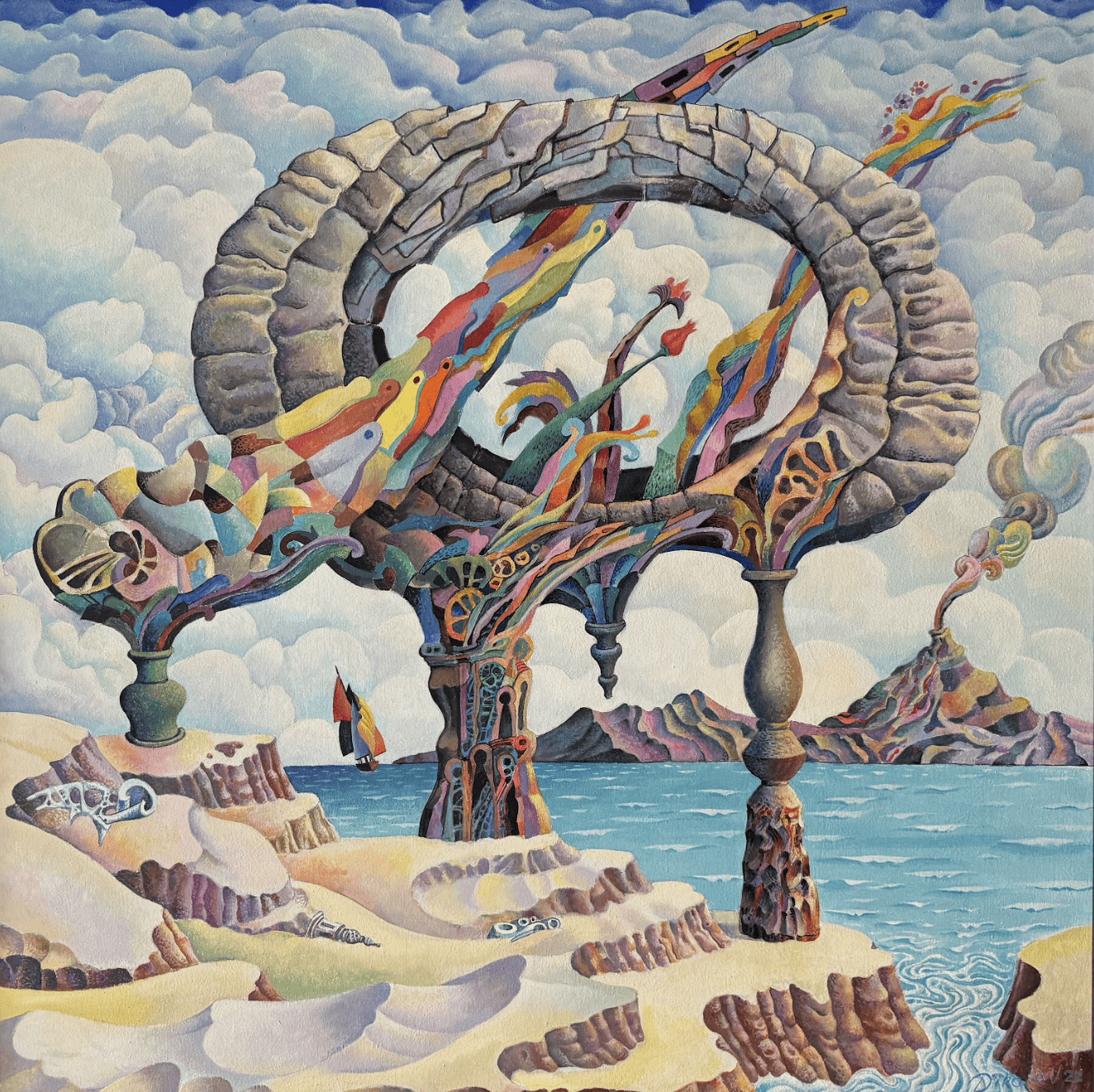

“Closer to Heaven,” 2022.

Courtesy of the Museum of Russian Art

The St. Paul-based, Ukrainian-born artist will tell you that many of these scenes have come to him through dreams. The majority of the canvases that surround him seem to be snapshots of the same world — windswept desert landscapes with impossible teetering monasteries and pillars and cloud trees.

He cites Salvador Dalí as an influence. The visual connection is clear: As in Dalí’s world, many of Dikarev’s subjects are in biblical-scale landscapes and precariously propped up and draped upon needly crutches (Think of Dalí’s “Sleep,” “Daddy Longlegs of the Evening – Hope!” and “The Great Masturbator.”)

But Dikarev is doing something entirely his own with the color palette. His is a world of exuberant, sandy pastels. In contrast, Surrealists like Dalí and Yves Tanguy and Max Ernst (Dikarev’s other influences), painted in more somber palettes and starker, shadowy contrasts. (Although a small side room at the museum features Dikarev’s darker impulses, or what Zavialova calls his “apocalyptic” section.)

Standing in front of the almost hypercolor “Transfiguration,” which plays with Eastern Orthodox iconography, Dikarev says his palette doesn’t come from this world. It can be both symbolic and harmonious. Or as Zavialova translates, it is “the internal vision of the color.”

“Portal,” 2021.

Courtesy of the Museum of Russian Art

On the surface, the difference is between a realm of nightmares — however seductive — and Dikarev’s more welcoming land of daytime dreams and cheerful mystery. There’s a hopeful and psychedelic quality to his art, sharing something with the great science fiction illustrations of the 60s and 70s, like the original cover art for Ursula K. Le Guin’s books as well as that of Frank Hebert’s “Dune” series.

In fact, the recently released “Dune: Part Two” is unexpectedly complementary to Dikarev’s exhibition. Both exist in worlds that are cryptic, with a range of religious undertones, while ultimately abiding by the rhythm of sand and wind.

And, like “Dune” and the early Surrealists, Dikarev also confronts the shadow of war. Dikarev says one of the most recent paintings in the show — the 2023 “Shot-gunned Summer” — is a direct reference to the Russian war in Ukraine.

Dikarev was born in a post-World War II Soviet Union and studied art in the thousand-year-old Ukrainian city of Uzhgorod. The Soviet Union, he says, was no fan of Surrealism. He moved to Minnesota in 1997.

With “Shot-gunned Summer” the palette is playing a trick: It’s a soft-hued world full of terrors, of fire and turbulence.

Translating for Dikarev, Zavialova relays, “It’s just an attempt to process the war.”

“Sad Cyprus,” 2020.

Courtesy of the Museum of Russian Art

As I pack up to leave the museum, Dikarev gently murmurs something to Zavialova. Zavialova turns and says: “You can’t leave yet!”

She asks me to follow her and Dikarev to the kitchen, explaining that today, March 8, is International Women’s Day. In Ukraine, there is a tradition of men giving women flowers. Dikarev, she says, brought flowers for all the women he would see at the museum. In the kitchen is a table sprouting with bouquets. They hand me a bunch of purple irises.

“Portal to the Surreal” is on view through June 2.