Join us in Atlanta on April 10th and explore the landscape of security workforce. We will explore the vision, benefits, and use cases of AI for security teams. Request an invite here.

The class-action copyright lawsuit filed by artists against companies providing AI image and video generators and their underlying machine learning (ML) models has taken a new turn, and it seems like the AI companies have some compelling arguments as to why they are not liable, and why the artists’ case should be dropped (caveats below).

Yesterday, lawyers for the defendants Stability AI, Midjourney, Runway, and DeviantArt filed a flurry of new motions — including some to dismiss the case entirely — in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, which oversees San Francisco, the heart of the wider generative AI boom (this even though Runway is headquartered in New York City).

All the companies sought variously to introduce new evidence to claim that the class-action copyright infringement case filed against them last year by a handful of visual artists and photographers should be dropped entirely and dismissed with prejudice.

The background: how we got to this point

The case was originally filed a little more than a year ago by visual artists Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan, and Karla Ortiz. In late October 2023, Judge William H. Orrick dismissed most of the artists’ original infringement claims, noting that in many instances the artists didn’t actually seek or receive copyright from the U.S. Copyright Office for their works.

However, the judge invited the plaintiffs to refile an amended claim, which they did in late November 2023, with some of the original plaintiffs dropping out and new ones taking their place and adding to the class, including other visual artists and photographers — among them, Hawke Southworth, Grzegorz Rutkowski, Gregory Manchess, Gerald Brom, Jingna Zhang, Julia Kaye, and Adam Ellis.

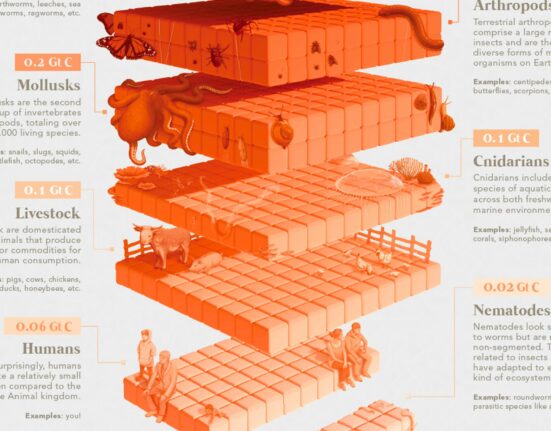

In a nutshell, the artists argue in their lawsuit that the AI companies, by scraping the artworks that the artists’ publicly posted on their websites and other online forums, or obtaining them from research databases (namely the controversial LAION-5B, which was found to include not just links to copyrighted works, but also child sexual abuse material, and summarily removed from public access on the web) and using them to train AI image generation models that can produce new, highly similar works, is an infringement of their copyright on said original artworks. The AI companies did not seek permission from the artists to scrape the artwork in the first place for their datasets, nor did they provide attribution or compensation.

AI companies introduce new evidence, arguments, and motion for dismissing the artists’ case entirely

The companies’ new counterargument largely boils down to the fact that the AI models they make or offer are not themselves copies of any artwork, but rather, reference the artworks to create an entirely new product — image generating code — and furthermore, that the models themselves do not replicate the artists’ original work exactly, and not even similarly, unless they are explicitly instructed (“prompted”) by users to do so (in this case, the plaintiffs’ lawyers). Furthermore, the companies argue that the artists have not shown any other third-parties replicating their work identically using the AI models.

Are they convincing? Well, let’s stipulate as usual that I’m a written journalist by trade — I am no legal expert, nor am I a visual artist or AI developer. I do use Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and Runway to make AI-generated artwork for VentureBeat articles — as do some of my colleagues — and for my own personal projects. All that noted, I do think the latest filings from the web and AI companies make a strong case.

Let’s review what the companies are saying:

DeviantArt, the odd one out, notes that it doesn’t even make AI

Oh, DeviantArt…you’re truly one of a kind.

The 24-year-old online platform for uses to host, share, comment on and engage with one another’s works (and each other) — known for its often edgy, explicit work and bizarrely creative “fanart” interpretations of popular characters — came out of this round of the lawsuit swinging hard, noting that, unlike all of the other plaintiffs mentioned, it’s not an AI company and doesn’t actually make any AI art generation models whatsoever.

In fact, to my eyes, DeviantArt’s initial inclusion in the artists’ lawsuit was puzzling for this very reason. Yet, DeviantArt was named because it offered a version of Stable Diffusion, the underlying open-source AI image generation model made by Stability AI, through its site, branded as “DreamUp.”

Now, in its latest filing, DeviantArt brings up the fact that simply offering this AI-generating code should not be enough to have it named in the suit at all.

As DeviantArt’s latest filing states:

“DeviantArt’s inclusion as a defendant in this lawsuit has never made sense. The claims at issue raise a number of novel questions relating to the cutting-edge field of generative artificial intelligence, including whether copyright law prohibits AI models from learning basic patterns, styles, and concepts from images that are made available for public consumption on the Internet. But none of those questions implicates DeviantArt…

“Plaintiffs have now filed two complaints in this case, and neither of them makes any attempt to allege that DeviantArt has ever directly used Plaintiffs’ images to train an AI model, to use an AI model to create images that look like Plaintiffs’ images, to offer third parties an AI model that has ever been used to create images that look like Plaintiffs’ images, or in any other conceivably relevant way. Instead, Plaintiffs included DeviantArt in this suit because they believe that merely implementing an AI model created, trained, and distributed by others renders the implementer liable for infringement of each of the billions of copyrighted works used to train that model—even if the implementer was completely unaware of and uninvolved in the model’s development.”

Essentially, DeviantArt is contending that simply implementing an AI image generator made by other people/companies should not, on its own, qualify as infringement. After all, DeviantArt didn’t control how these AI models were made — it simply took what was offered and used it. The company notes that if it does qualify for infringement, that would be an overturning of precedent that could have very far-reaching and, in the words of its lawyers’, “absurd” impacts on the entire field of programming and media. As the latest filing states:

“Put simply, if Plaintiffs can state a claim against DeviantArt, anyone whose work was used to train an AI model can state the same claim against millions of other innocent parties, any of whom might find themselves dragged into court simply because they used this pioneering technology to build a new product whose systems or outputs have nothing whatsoever to do with any given work used in the training process.”

Runway points out it does not store any copies of the original imagery it trained on

The amended complaint filed by artists last year cited some research papers by other machine learning engineers that concluded the machine learning technique “diffusion” — the basis for many AI image and video generators — learns to generate images by processing image/text label pairs and then trying to recreate a similar image given a text label.

However, the AI video generation company Runway — which collaborated with Stability AI to fund the training of the open-source image generator model Stable Diffusion — has an interesting perspective on this. It notes that simply by including these research papers in their amended complaint, the artists are basically giving up the game — they aren’t showing any examples of Runway making exact copies of their work. Rather, they are relying on third-party ML researchers to state that’s what AI diffusion models are trying to do.

As Runway’s filing puts it:

“First, the mere fact that Plaintiffs must rely on these papers to allege that models can “store” training images demonstrates that their theory is meritless, because it shows that Plaintiffs have been unable to elicit any “stored” copies of their own registered works from Stable Diffusion, despite ample opportunities to try. And that is fatal to their claim.”

The complaint goes on:

“…nowhere do [the artists] allege that they, or anyone else, have been able to elicit replicas of their registered works from Stable Diffusion by entering text prompts. Plaintiffs’ silence on this issue speaks volumes, and by itself defeats their Model Theory.”

But what about Runway or other AI companies relying on thumbnails or “compressed” images to train their models?

Citing the outcome of the seminal lawsuit of the Authors Guild against Google Books over Google’s scanning of copyrighted work and display of “snippets” of it online, which Google won, Runway notes that in that case, the court:

“…held that Google did not give substantial access to the plaintiffs’ expressive content when it scanned the plaintiffs’ books and provided “limited information accessible through the search function and snippet view.” So too here, where far less access is provided.”

As for the charges by artists that AI rips-off their unique styles, Runway calls “B.S.” on this claim, noting that “style” has never really been a copyrightable attribute in the U.S., and, in fact, the entire process of making and distributing artwork, has, throughout history, involved artists imitating and building upon on others’ styles:

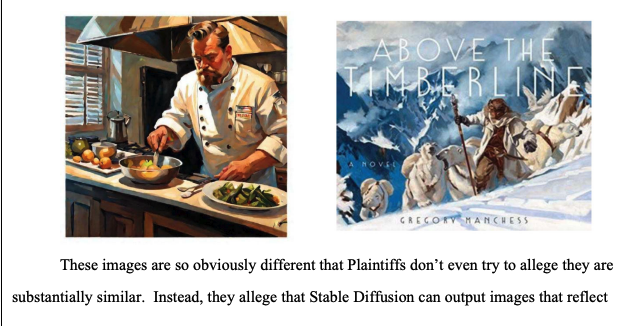

“They allege that Stable Diffusion can output images that reflect styles and ideas that Plaintiffs have embraced, such as a “calligraphic style,” “realistic themes,” “gritty dark fantasy images,” and “painterly and romantic photography.” But these allegations concede defeat because copyright protection doesn’t extend to “ideas” or “concepts.” 17 U.S.C § 102(b); see also Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186, 219 (2003) (“[E]very idea, theory, and fact in a copyrighted work becomes instantly available for public exploitation at the moment of publication.”). The Ninth Circuit has reaffirmed this fundamental principle countless times.14 Plaintiffs cannot claim dominion under the copyright laws over ideas like “realistic themes” and “gritty dark fantasy images”—these concepts are free for everyone to use and develop, just as Plaintiffs no doubt were inspired by styles and ideas that other artists pioneered before them.“

And in an absolutely brutal, savage takedown of the artists’ case, Runway includes an example from the artists’ own filing that it points out is “so obviously different that Plaintiffs don’t even try to allege they are substantially similar.”

Stability counters that its AI models are not ‘infringing works,’ nor do they ‘induce’ people to infringe

Stability AI may be in the hottest seat of all when it comes to the AI copyright infringement debate, as it is the one most responsible for training, open-sourcing, and thus, making available to the world the Stable Diffusion AI model that powers many AI art generators behind-the-scenes.

Yet its recent filing argues that AI models are themselves not infringing works because they are at their core, software code, not artwork, and that neither Stability nor the models themselves are encouraging users to make copies or even similar works to those that the artists are trying to protect.

The filing notes that the “theory that the Stability models themselves are derivative works… the Court rejected the first time around.” Therefore, Stability’s lawyers say the judge should reject them this time.

When it comes to how users are using the Stable Diffusion 2.0 and XL 1.0 models, Stability says it is up to them, and that the company itself does not promote their use for copying.

Traditionally, according to the filing, “courts have looked to evidence that demonstrates a specific intent to promote infringement, such as publicly advertising infringing uses or taking steps to usurp an existing infringer’s market.”

Yet, Stability argues: “Plaintiffs offer no such clear evidence here. They do not point to any Stability AI website content, advertisements, or newsletters, nor do they identify any language or functionality in the Stability models’ source code, that promotes, encourages, or evinces a “specific intent to foster” actual copyright infringement or indicate that the Stability models were “created . . . as a means to break laws.””

Pointing out that the artists’ jumped on Stability AI CEO and founder Emad Mostaque’s use of the word “recreate” in a podcast, the filing argues this alone is not enough to suggest the company was promoting its AI models as infringing: “This lone comment does not demonstrate Stability AI’s “improper object” to foster infringement, let alone constitute a “step[] that [is] substantially certain to result in such direct infringement.”

Moreover, Stability’s lawyers smartly look to the precedent set by the 1984 U.S. Supreme Court decision in the case between Sony and Universal Studios over the former’s Betamax machines being used to record copies of TV and movies on-air, which found that VCRs can be sold and don’t on their own qualify as copyright infringement because they have other legitimate uses. Or as the Supreme Court held back then: “If a device is sold for a legitimate purpose and has a substantial non-infringing use, its manufacturer will not be liable under copyright law for potential infringement by its users.”

Midjourney strikes back over founder’s Discord messages

Midjourney, founded by former Leap Motion programmer David Holz, is one of the world’s most popular AI image generators with tens of millions of users. It’s also considered by leading AI artists and influencers to be among the highest quality.

But since its public release in 2022, it has been a source of controversy among some artists for its ability to produce imagery that imitates what they see as their distinctive styles, as well as popular characters.

For example, in December 2023, Riot Games artist Jon Lam posted screenshots of messages sent by Holz in the Midjourney Discord server in February 2022, before Midjourney’s public launch. In them, Holz described and linked to a Google Sheets cloud spreadsheet document that Midjourney had created, containing artist names and styles that Midjourney users could reference when generating images (using the “/style” command).

Lam used these screenshots of Holz’s messages to accuse the Midjourney developers of “laundering, and creating a database of Artists (who have been dehumanized to styles) to train Midjourney off of. This has been submitted into evidence for the lawsuit.”

Indeed, in the amended complaint filed by the artists in the class action lawsuit in November 2023, Holz’s old Discord messages were quoted, linked in footnotes and submitted as evidence that Midjourney was effectively using the artists’ names to “falsely endorse” its AI image generation model.

Updated Saturday, Feb. 10, 2024, 9:39 pm ET

I heard back from Max Sills, Midjourney’s lead counsel, after this piece was published and he pointed out I missed another document that was filed which contained the substantive argument the Midjourney legal team was making in the case, so I’ve corrected and updated my piece below accordingly. Thank you, Max.

However, in one of Midjourney’s latest filings in the case from this week, the company’s lawyers have gone ahead and added direct links to Holz’s Discord messages from 2022, and others that they say more fully explain the context of Holz’s words and the document containing the artist names — which also contained a list of approximately 1,000 art styles, not attributed to any particular artist by name.

Holz also stated at the time that the artist names were sourced from “Wikipedia and Magic the Gathering.”

Moreover, Holz sent a message inviting users in the Midjourney Discord server to add their own proposed additions to the style document.

As the Midjourney filing states: “The Court should consider the entire relevant segment of the Discord message thread, not just the snippets plaintiffs cited out of context.”

In a separate filing, Midjourney’s lawyers note these messages between Holz and Midjourney’s early users show that their claim that Midjourney used the artists referenced to “falsely endorse” his company’s products is not possible, as the exchange conveys they came not from the artists’ themselves, but from web research.

In a succinct but pointed barb, the Midjourney lawyers write:

“Plaintiffs do not contend that anything in the post was inaccurate, identify any user who was supposedly confused, or explain why any user following Midjourney’s Discord channel might mistakenly believe that any artist listed in the Name List endorsed the Midjourney platform.”

The earlier document also points out an apparent error in the artists’ amended complaint, which states that Holz said Midjourney’s “image-prompting feature…looks at the ‘concepts’ and ‘vibes’ of your images and merges them together into novel interpretations.”

Midjourney’s lawyers point out, Holz wasn’t referring to Midjourney’s prompting when he typed that message and sent it in Discord — rather, he was talking about a new Midjourney feature, the “/blend” command, which combines attributes of two different user-submitted images into one.

Still, there’s no denying Midjourney can produce imagery that includes close reproductions of copyrighted characters like the Joker from the film of the same name, as The New York Times reported last month.

But so what? Is this enough to constitute copyright infringement? After all, people can copy images of The Joker by taking screenshots on their phone, using a photocopier, or just tracing over prints, or even looking at a reference image and imitating it freehand — and none of the technology that they use to do this has been penalized or outlawed due to its potential for copyright infringement.

In fact, Midjourney’s lawyers make this very same argument in one of the filings, noting: “A photocopier is “capable” of reproducing an identical copy. So, too, is a web browser and a printer. That does not make the software underlying those tools an infringing copy of the images they produce.”

As I’ve said before, just because a technology allows for copying doesn’t mean it is itself infringing — it all depends on what the user does with it. We’ll see if the court and judge agree with this or not. No date has yet been set for a trial, and the AI and web companies named in this case would certainly prefer to see the case dismissed before then.