Courtesy the estate of Geoffrey Holder

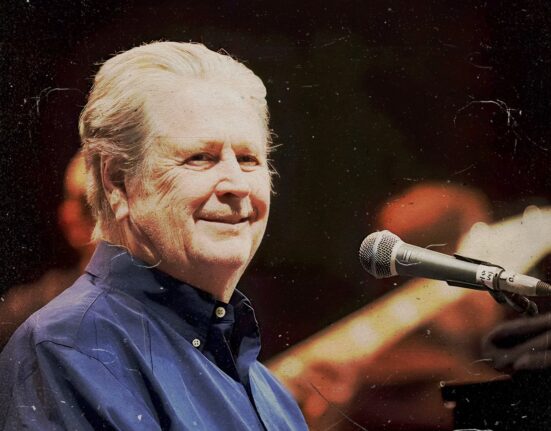

Geoffrey Holder is famous for many things. Most people will likely know him for playing a Bond villain in Live and Let Die, for directing the Broadway musical The Wiz and designing costumes for it, for being a principal dancer of the Metropolitan Opera Ballet in the 1950s, for collaborating with choreographer Alvin Ailey or dancer Josephine Baker, for being the face of 7 Up commercials, or for being a general man about town, with an infectious laugh and astute sense of style, in the New York scene. Only a select few, however, know him for the central passion of his life: his art practice. But that is beginning to change.

“Painting came first,” Léo Holder, the artist’s son and the steward of his father’s art for more than a decade, told ARTnews, noting that his father had his first art exhibition at 14, sold his paintings to finance his move from Trinidad to New York in 1953, and was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for his art in 1956. “It just so happens that everything else he does is an extension of the painting, but painting has always been the nucleus.”

With an aim to correct the record of his father’s artistic contributions and rebut any claims that Holder was merely a Sunday painter, Léo said even he is still learning about Holder père: “Even though I’ve grown up with most of these, I’m always making discoveries—it’s literally the tip of the iceberg.”

When we last spoke, in February, only 250 paintings in the estate’s collection had been catalogued. There are likely dozens more that are also out in the world still, since he painted every day, often late into the night, and distributed many to his family, friends, and others in his circle, including the likes of actress and singer Diahann Carroll. “There’s some people who work in the medium, and there’s some people who are the medium, and he’s the latter, in the sense that everything about him is art,” said Léo, who often speaks reverently about his father.

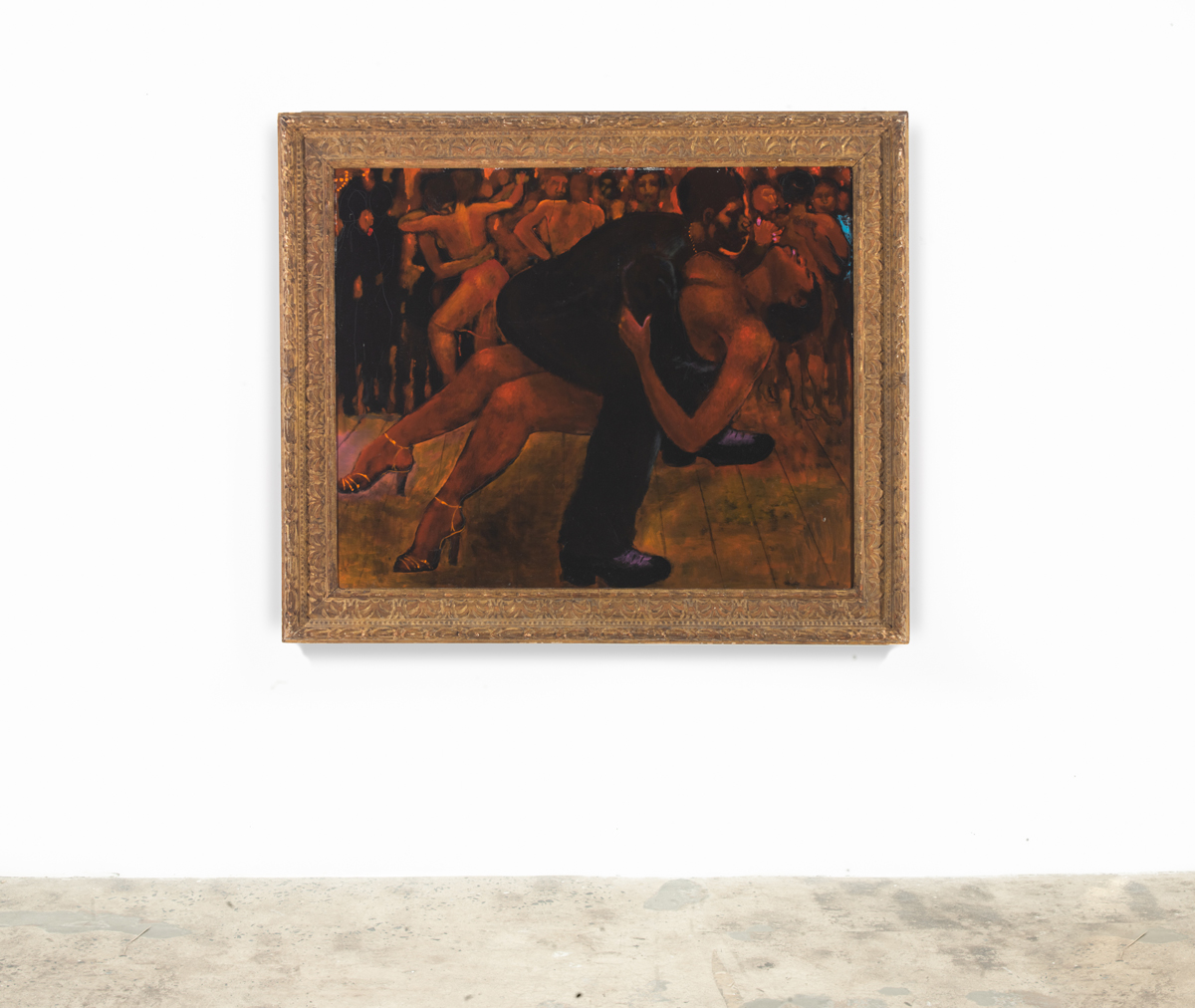

Geoffrey Holder, Getting Down / Showing Off the Dip, ca. 1990s.

Courtesy the estate of Geoffrey Holder and James Fuentes

The importance of Holder as an artist is beginning to come into focus, in no small part due to two exhibitions mounted by James Fuentes gallery—one in New York in 2022 curated by critic Hilton Als, the other in 2024 in Los Angeles curated by Erica Moiah James, an art historian who focuses on the Caribbean and African diasporas. But these shows are really just scratching the surface of an oeuvre belonging to an artist who has, ironically, been famous for everything except his art.

“I’m from the Caribbean, so I’ve always known about him—I don’t think there’s a time in my life when I didn’t know about Geoffrey Holder,” James told ARTnews. But she didn’t engage with Holder’s artistic work until after his death in 2014, when Léo and Carmen de Lavallade, Geoffrey’s widow and Léo’s mother, reached out to her. She continued, “Generally, people thought of him as a dilettante because he acted, he choreographed, he painted, he wrote books. I think people found it intimidating that he was great at everything—one of those rare people who just were talented at almost everything that he did. If he put his mind to something, it was going to be excellent.”

Léo Holder sorts through the New Jersey warehouse that stores Geoffrey Holder’s art.

Courtesy the estate of Geoffrey Holder

Shortly after Léo and de Lavallade contacted her, James visited a warehouse in New Jersey that was chockful of Holder’s art, with hundreds upon hundreds of canvases, drawings, photographs, and much more in countless boxes. Léo has described it as “a combination of King Tut’s tomb and the warehouse from Citizen Kane—and all of it is art.”

“It was clear to me immediately that this person was someone who lived for the future—that he knew that he wasn’t being taken as seriously as he needed to be in his lifetime, but that history would absolve him,” James said. “He kept everything, as if he were keeping it so that one day someone would go through it and see the kind of breadth of his whole imagination, which I immediately understood was vast.”

Installation view of “Geoffrey Holder: Pleasures of the Flesh,” curated by Hilton Als, at James Fuentes, New York, 2022.

Courtesy the estate of Geoffrey Holder and James Fuentes

The 2022 Als-curated exhibition included one work Léo only discovered in the past several years. One of the earliest paintings in that exhibition, it had been tucked away for decades among other works.

Geoffrey Holder, 78 Richmond St., 1950.

Courtesy the estate of Geoffrey Holder and James Fuentes

When Léo found it, he couldn’t quite make out the title of the work, which was the address of his father’s family home in Trinidad. Titled 78 Richmond St. (1950), the painting shows the artist with his father and his older brother, Boscoe, who was an influence and mentor to Geoffrey. “Everything Geoffrey did, Boscoe did first,” Léo said.

Growing up in Port of Spain, Holder was surrounded by creativity, with everyone in the family being adept at designing clothes, as he recalled in a 2001 biography by New York Times ballet critic Jennifer Dunning. From a young age, Holder said he wanted to be an artist. But Boscoe’s restless pursuit of all the arts also pulled Holder in those different directions, from piano to dance to staging theatrical performances. And the family house would be a locus for people to see the brothers’ paintings and dance performances, even after Boscoe left for London in 1950.

While his dance company traveled around the Caribbean and eventually to New York, where he would officially move in 1953, he kept painting. Holder always worked in a figural mode, painting people with elongated forms who appear to be caught mid-dance in some cases. In others, they are shown going about their days on a busy cityscape, or in lush landscapes, or in contemporary updates of religious scenes. Some were composed specifically for the ornate gold frames in which they hang. James said Holder’s intention in all these works was to show “the life of Black people in every facet of their being and in their personal spaces” and to convey “the full humanity of Black women” in particular.

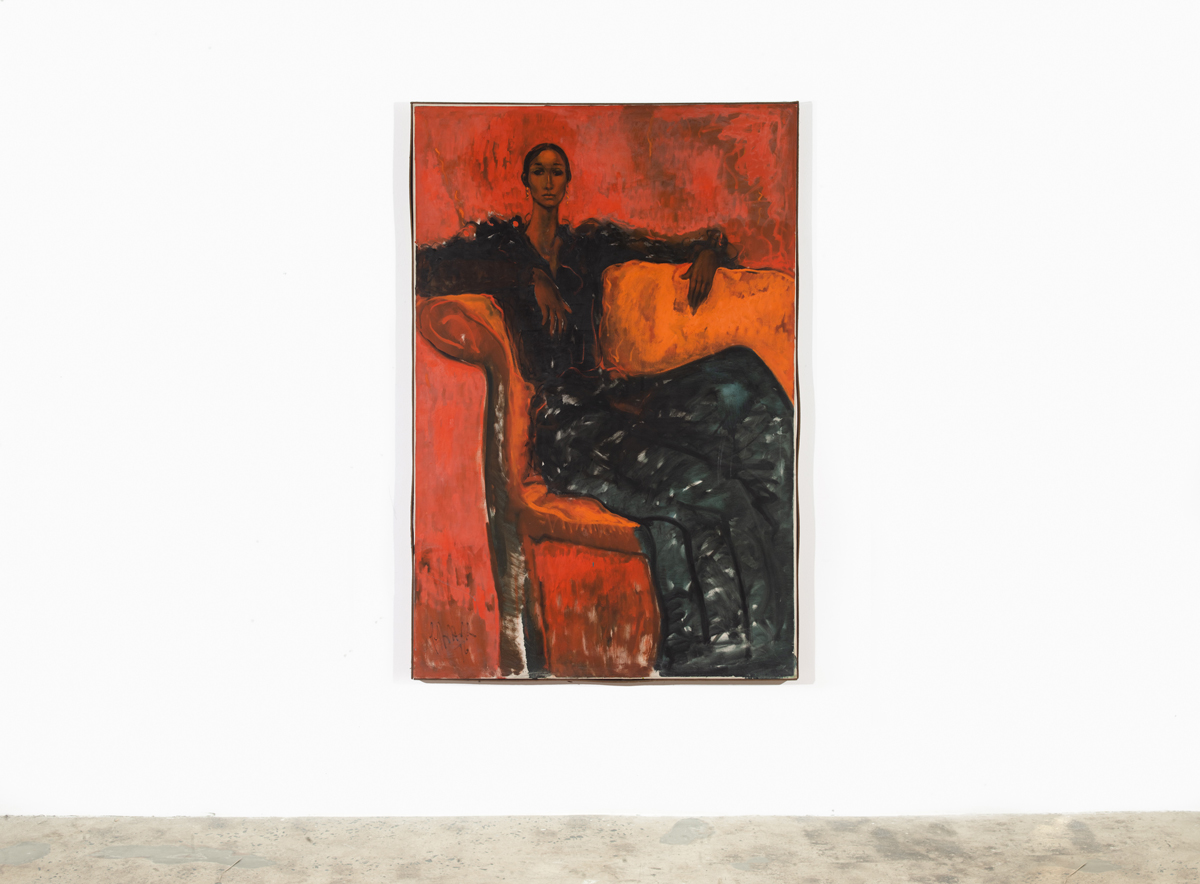

Geoffrey Holder, Portrait of Carmen de Lavallade, 1976.

Photo Jason Mandella/Courtesy the estate of Geoffrey Holder and James Fuentes

Holder’s most frequent muse was none other than de Lavallade, an acclaimed dancer in her own right who in the early ’50s had also just recently moved to New York, from Los Angeles. They met when they both starred in the 1954 Broadway musical, House of Flowers, an adaptation of a Truman Capote short story, and were married by 1955, with Léo coming two years later.

At the recent LA exhibition, it was Holder’s 1976 portrait of de Lavallade that drew you in. In the work, de Lavallade is elegantly posed in the corner of an ochre-colored couch. She’s shown in flowing black clothes and set against a vibrant red-orange background. Léo said the work was a personal favorite of Holder. “If he were still alive,” Léo added, “it wouldn’t be for sale.”

Holder was able to intuit the composition largely from his own imagination, asking de Lavallade to sit for just a few minutes before he finished the painting “from his head,” Léo said, adding, “He had a tendency to watch people not when they’re on, but just when they start getting into their inner thoughts.”

Geoffrey Holder in an undated photograph with his paintings.

Courtesy the estate of Geoffrey Holder

“People say people are ahead of their time. Geoffrey was that, but he also was just him,” James said. “He insisted that how he saw was a valuable way of seeing. And if it was out of step with other people, that was okay, because that was them. He was doing his thing.”

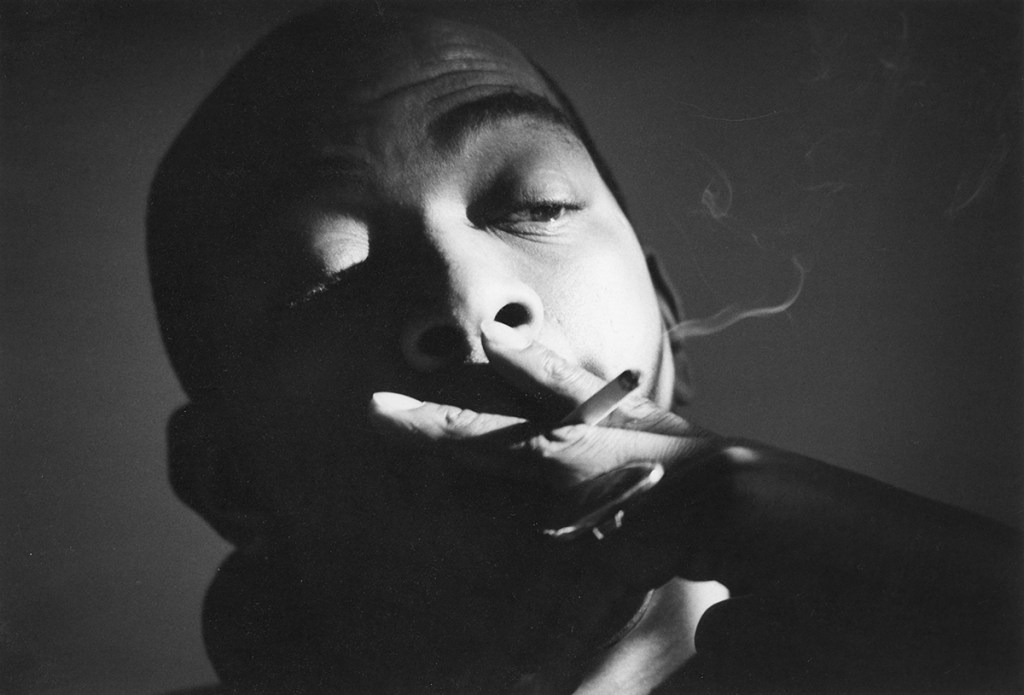

Holder paid just as much attention to how he presented himself to the world. Shortly after arriving in New York in the ’50s, Holder met Carl Van Vechten, a white photographer who is best-known for chronicling the Harlem Renaissance. Van Vechten asked Holder to pose for him, to which Holder agreed. In one image, Holder, wearing only a loincloth and a large necklace, crouches on the floor, his eyes closed as if he is caught in some meditative state.

“He’s dancing—he’s playing the exotic, but he clearly understood what was going on,” James said. But according to James, Holder was assertive about “being presented in a particular way” and refused to simply be exoticized. He returned the next day with a cache of his paintings to show Van Vechten, insisting on being photographed with them. Van Vechten agreed, and the dynamics of the resulting images are completely changed.

“He’s in control—he’s completely taken over the gaze, that sort of fetish eye. He comes back and interrupts it, like, I’m going to use this for my own purposes,” James added.

Geoffrey Holder, Blue Bed, 1980.

Photo Jason Mandella/Courtesy the estate of Geoffrey Holder and James Fuentes

Holder spent the last three years of his life in a long-term care facility. In 2011, in his early 80s, he had a major fall and seriously injured himself, and he was also diagnosed with dementia around that time. But that didn’t stop Holder from creating. He would make art on “anything he could get his hands on: corrugated cardboard, plastic bags, Styrofoam cups, electrical tape, contact paper, and cheap poster-frame from Michael’s,” Léo said. “Out of that came at least 400 pieces.”

“Oh my goodness, his creativity—this guy is on another level,” James said of those final works, which are mostly collages. “He used the materials in a way where I didn’t recognize them at first—he had manipulated the materials so much that they were completely defamiliarized.”

Given that many of Holder’s materials cannot be easily archived, they will present the biggest challenge for the estate to catalogue and conserve. And when those finally do go on view, a whole different version of Holder will come into focus at a moment when his life’s work is primed for an essential reevaluation.

A couple dozen of recently catalogued paintings by Geoffrey Holder.

Courtesy the estate of Geoffrey Holder

In 2020, James, who is an assistant professor at the University of Miami, received a $200,000 grant from the Mellon Foundation to document and research Holder’s archive, and then in 2022, she received one for $25,000 from the Terra Foundation to organize a two-day symposium on the artist that will form the basis of a scholarly publication on him. A guiding principle of the project, James said, is “how to make Black archives more accessible.”

The recent exhibitions, on the other hand, are meant “to understand the importance of value [in the art market] and of getting that work out there,” James said. “I think people can continue to try to box him in, but the story itself makes that box a frame, and he really exceeds that frame very quickly.”

Geoffrey Holder, Maria Virginia, 1983.

Courtesy the estate of Geoffrey Holder and James Fuentes

Even until his final days, Holder was editing how his story would be told. In 2014, the year of his death, the nonprofit Lifeforce in Later Years (LiLY) honored Holder with its Legacies Award, the ceremony for which included a pop-up exhibition of some of Holder’s paintings. He looked at one, Maria Virginia (1983), featuring a Black Madonna holding a Black Christ child, with Mannerist-like proportions.

“‘There’s something missing,’” Léo, standing in front of the painting during the recent LA show, recalled his father saying. “It had been in our possession for several years. And I said, ‘You’re not changing anything.’ And, of course, he gets his way.”

Holder entrusted a friend to get him a white paint marker from a nearby art supplies store. He added squiggles around her head. The carnations he had painted into her hair decades ago now reminded him of headphones. Léo was apoplectic, but that experience is one he’ll never forget. It would be the last canvas Holder “personally touched with paint,” according to Léo.

Léo added, “He always knew what he was doing. Anytime you second guessed him, you would figure out later that yeah, you were wrong.”