Three emerging artists in the UAE are heading to the world’s most prestigious art event: the Venice Biennale.

Almaha Jaralla, Latifa Saeed and Samo Shalaby are set to showcase their works as part of Beyond Emerging Artists. Abu Dhabi Art organises the annual initiativeand supports emerging creatives in the UAE, commissioning them to create new works.

Jaralla, Saeed and Shalaby were the artists selected last year alongside art historian Morad Montazami as curator. He works with the three artists as they develop their works.

The trio unveiled the commissioned works in a group exhibition at Art Abu Dhabi in November. They will present those same artworks in Venice, which will be held from April 20 to November 24. The group will also display pieces at the city’s Marignana Arte Gallery between April 16 and May 15.

“Abu Dhabi Art is committed to nurturing emerging artists and providing them with a platform to broaden the reach of their work,” Dyala Nusseibeh, director of Abu Dhabi Art, said.

“The Venice Biennale presents a remarkable opportunity for these young artists to reach new audiences and represent the UAE on a global stage.”

The three differ in their styles and how they tackle their subject matter. Yet their works bear certain similarities in the way they explore contrasts between private and public spaces, as well as individual and collective memory. They also reflect on historical elements, juxtaposing them with contemporary perspectives and technology.

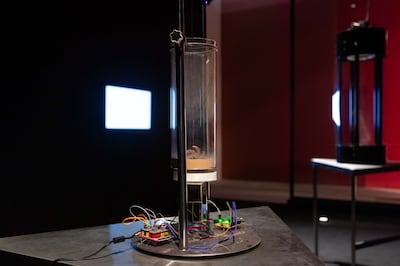

In Dust Devils, for instance, Saeed pays tribute to a natural phenomenon that is a unique but familiar sight to those in the region. The Emirati artist manifests the natural phenomenon through artworks that incorporate smoke machines, holograms and electromagnetic technology.

Dust Devils is, in a way, “a reflection and representation of my region’s essence”, Saeed said, adding that the work creates a “dialogue between nature and innovation”.

He said: “The experimental artworks evoke a sense of wonder and contemplation inviting viewers to explore nature’s selective, intricate harmony of the four elements: air, fire, water, and earth.”

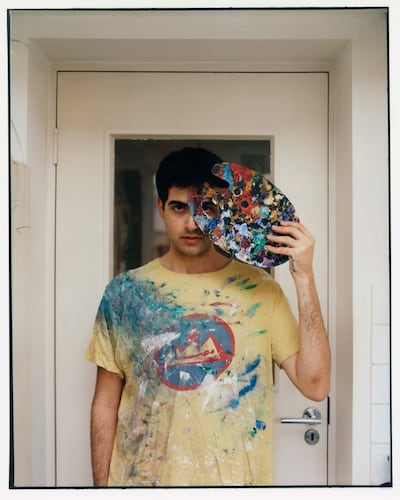

Shalaby’s What Lies Beneath presents a panoply of artworks that range from jewellery pieces to paintings. Beyond Emerging Artists displayed the series at Abu Dhabi Art in a labyrinthine space lit and curtained with theatrical drama. Its presentation at the Venice Biennale, however, will be relatively more contained and straightforward.

It is unlikely to detract from the spirit of the installation. If anything, What Lies Beneath will resonate in a novel way with its presentation at Venice, given that the series reflects on several historical art movements that were prevalent in Europe. Some, such as the Renaissance, were even born in Italy.

“It’s definitely coming full circle, because a lot of my visual style is influenced by the Italian Renaissance,” Shalaby said.

The Egyptian-Palestinian artist added What Lies Beneath can be seen as a distillation of all the things that inspire him.

“What Lies Beneath was basically a build-up of everything that I’ve ever liked in one kind of space,” he added. “[It spans] painting to costume design to theatre, jewellery, art history. It merges the contemporary with the historical, creating an atmospheric, immersive experience.”

The Memento Mori pieces, for example, take their cue from the lover’s eye jewellery – a trend during the Victorian era where painted depictions of a person’s eye (or nose, or lips) were given to their loved ones. He said: “It was something very intimate that was kept secret and hidden in your pouch or in the pin of your lapel. They were sentimental tokens of affection, which I wanted to bring back in a contemporary way.”

Juxtaposing these smaller pieces are the larger paintings that have been derived from Shalaby’s love for the theatre. The paintings often feature a range of costumed characters and examine themes that range from death to masquerade balls. It is particularly these works that will perhaps feel right at home in Venice, Shalaby said.

“They are very much shaped by my love of masquerade parties, films like Eyes Wide Shut, really theatrical displays of costume,” he said. Then there are the paintings that Shalaby produced on surfaces that beckoned Baroque interior design and architecture. While he created many of the surfaces himself, one was produced on an antique wooden headboard. The work is titled Fantome Fete (The Festival of Phantoms) and, as its title suggests, features ghostly figures (some of whom are headless) performing and dancing in a ball illuminated in an eerie green.

Shalaby said taking his artworks to Venice will be a career-defining moment. “This has been a dream of mine ever since I started thinking about art, to exhibit in Venice, especially during the Biennale,” he added.

Finally, with Crude Memory, Jaralla also explores somewhat spectral spaces. These, however, are much closer to home.

The Emirati artist is presenting a fictional recreation of Al Ruwais, a city 240km west of Abu Dhabi. The town was developed in the 1970s by Adnoc as an industrial stronghold. Crude Memory touches on this, exploring the urban and private landscapes as they existed in the 1970s and 1980s. The work explores the modernity that swept the nation during the oil boom. It also imagines the urban fabric, as economic priorities move away from oil and towards other sectors.

Through sculptures and photographs, the artist presents an architecture that blends post-modern values with vernacular approaches. There is a poignant undertone to many of the works, however, showing abandoned spaces and vestiges of once-lush gardens. In that way, Crude Memory looks at how the environment will fare within the architectural and industrial ruins.

Jaralla said taking Crude Memory to Venice offers a chance to explore the meeting point between the histories of the UAE and Italy, along with their architectural and environmental considerations.

“Showing in Venice with Abu Dhabi Art is really interesting for me because of the history of pearl trading between our part of the world and Europe – in particular Venice,” Jaralla said. “Pearl diving was crucial for our economy before the oil boom that was to change our urban fabric. As our towns and cities transform even further, how will we remember the architectural remains of our not-so-distant past, that are already disappearing?

“Venice, like Abu Dhabi, is an island but whilst we grapple with radical change, in what seems an incredibly short time frame, Venice has suffered centuries of flooding and damage to its building and architecture,” she said. “I think there are interesting conversations to be held about the architectures of both places.”

Updated: April 15, 2024, 3:06 AM