Musician and visual artist Daniel Blumberg discusses discovering new joys in film scoring, collaboration versus solitude, and how age is just a number.

As a musician and an artist, it seems like you’re always on some kind of adventure.

I’m actually going on Sunday to record reverb impulses in Carrera [Tuscany, Italy] in a marble quarry. To me, “experimental” means that at the moment I’m just thinking, “oh my god, what am I doing?” I literally don’t even know. I’m just gonna have to be reading up on how to do that… [laughs]

Just learning as you do it?

Yeah. It definitely feels like the right thing to do, but I have no idea how that type of process might inform something else. It’s for a project—the artist I’m working with on it, we did another project together last year, in Berlin, where everyone who came into the museum had their hearts mic’d up. It was an orchestra of heartbeats for 24 hours. People just came.

There was a maximum of 24 people in the space; it was a really nice, reverberant space, and everyone was completely silent. People would sit down and listen to each other’s hearts, basically. So when there was two people, it was really amplified, so like, “Boom!…Boom!…Boom…Boom!” and then when there was four it would be like “Boom, Boom, Boom, Boom!” and then 24, it was like [makes loud, crashing sounds] it was crazy. Even just technically, it’s interesting, how to do that. Like mic’ing up, when you put something like that out there.

Your new album GUT as the title implies goes a bit south of the heart. It was at least partly prompted by an intestinal illness you suffered a couple of years ago?

I had never been physically ill before, in my life, and then when I was 30, just after [scoring the Mona Fastvold film] The World To Come, I got ill. It was a big thing to deal with. I didn’t really know about illness, but—naturally, it just sort of fell into the way that I write. I wasn’t surprised that it started to bleed into the writing of the record because it took the best part of two years to actually be more normal again.

But, “gut” is also a word that just came to me. I thought it was amazing, visually, as well. I looked it up, and [looking through pages of a notebook], I had all the definitions written down in the studio, when I started to write. Obviously, it refers to your gut, which I was having issues with, but it’s also the essence of something…the inner parts, or the essence. Or, your gut response, your instinctive, emotional response. Or, if you “have guts” you have courage, and determination. Or, a toughness of character. “Misery guts”? Right? Like, I’m an emo artist. [laughs] And then there are weird things like removing—to “gut” something is to remove the internal parts, of a building or a structure. Or, to remove the intestines or something.

Improvisation and collaboration have been key to your music in the past decade or so, on your own records, with players like Tom Wheatley, Billy Steiger, Ute Kannegiesser, and on projects like GUO, your duo with saxophonist Seymour Wright. But GUT was pretty much just all you.

That’s been the recurring theme with this moment, and this record. Normally I will write stuff—which is always a solitary process—and then the payoff for me has been to bring it to these brilliant musicians, and spend time with it, working on them, and then of course, playing live shows. But with this record, it seemed, I was here, alone for so long, and not really playing music with other people, because of the pandemic. It seemed kind of inappropriate to bring other people into this kind of piece.

And, personally I love improvised music and I mainly listen to improvised music. With GUT, I was recording all on my own, and it was really important for me to do the core of the record in one take. It’s that kind of micro-instinct of like, when the song stops, when you pick up the next instrument. And the drums were all done in one take.

I mean, it’s definitely not an improvised record, it was composed and all. But I think that sort of process, of playing with people and improvising, it always has an effect on the work. It’s the norm for me. And I think, definitely if I’m collaborating with people it’s on the basis that we have a mutual understanding, creatively, but also just understanding the way we treat people—it extends to lots of other things.

I always think about Shadows, the Cassavetes film [1959] where he tried to make an improvised film. It’s got this energy where you can imagine he had these workshops with the actors. It had that energy, but they obviously didn’t all just go, “Right, let’s do a film!” and a week later it’s this beautifully formed thing. [laughs]

Before you got into writing the album, in the early COVID days, it was your drawing that sustained you.

Yeah, I mean the pandemic, it was cool because I had just finished this film score, and I was getting more ill, and I just needed some space from like people coming to the studio every day. It was nice at the start, but then eventually I could just draw. And also it was too dangerous for me to play with other people. Drawing made sense, during the pandemic and during those years in the studio. Whereas music, it didn’t make sense. It was definitely the only moment where I didn’t really work on music.

I wasn’t worried about it or anything, I just felt that it was quiet, and I felt like working on my drawing. But then, I work with an artist called Elvin Brandhi and we have a duo together, BAHK. We’ve never released anything formally, but we did a residency in Lisbon [in Oct-Nov 2020]. It was the first time I had worked with someone else, during that time. I think it began this process of writing. We always make lots of music and films and weird things, but after that was when I started to get that energy, and then eventually I just started writing, and it all came together quite quickly.

So one project can inspire you on another front?

That’s one of the things with my work. When I make a record, or with The World To Come, one of the things was like in the process, as you’re working, you have ideas about other things that you can do. It’s exciting! You’re always thinking beyond. I always write a lot of notes, when I record. A lot of recording is problem-solving. It’s sort of similar to a film set. You’re literally just problem-solving. It’ll be like, you’ve got an idea, like, “Oh, if these microphones are pointing there, then they’re gonna pick up some of that, so how can we limit that problem?” You’re constantly experimenting.

On GUT you experimented with different types of mic techniques?

I wanted to literally swallow one of the songs. I had it playing through the speakers and amplified through my Neumann, and the microphone was pointing at the speakers and then I put it in my mouth, so that the song was literally being recorded from the inside of my mouth. It’s the song “HOLDBACK” and all of the reflections of my mouth and were putting the song in this weird sort of phase sound. Seymour, the saxophonist I work with, he was someone that I spoke to a lot. He would come and listen to the recordings, and we would talk about it. Working on my own I think I still rely a lot on some of these friends, and then of course Pete [Walsh] who mixed it, we were in touch about everything throughout.

We’ve known each other more than a decade and I’ve seen you go from an indie rock band to leaning heavily into visual art—drawing and watercolors—then really rediscovering music through improvisational and experimental work, and more recently film scoring. What’s your relationship to past work? Do you tend to cringe or feel like you just can’t relate to something you made five, 10 years ago?

Yeah definitely, when you’re starting—or I started at 15, making music—and when you’re growing and discovering what you like and don’t like and stuff, I think yeah, I was always horrified of the stuff I’d done before. But it’s plateaued a bit, and over the last 10 years or something, um, or nine years, maybe, there’s been a process where it changes, incrementally. Sometimes I think it’s the last thing I’ve done. Like, with the record this time I was definitely more reactive to the last record I made in a way that I found funny. I was listening to it thinking, “Wow, I just wouldn’t…” I was critical.

This was [2020’s] On&On?

Yeah, I was critical of it in quite a productive—like, you find that it almost provokes a reaction in you sometimes, in a different direction?

You exited the pop and rock world quite a long time ago now, where “success” is pretty clearly quantified by a few metrics. What does “success” for the artist you are today look like?

If you think you’ve done your best. That’s the first part. When there’s a nagging thing of, “Oh, we could have actually tried that,” less so. That’s a nice thing to not have to deal with. If you feel like you’ve left no stone unturned, then there’s a sort of relaxation.

Your next major project is scoring your friend Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist. The film was pushed back a few times, and just shot this spring. Were you able to do early work on it, work on your own record, and come back to it? Or can you not do that sort of back-and-forth?

No, I’ve become quite mono, specially with the song stuff, I really wanted to finish this album before Brady started to shoot, because his film means a lot to me. It’s similar to working on one of my projects. It’s important that I make something really good for his beautiful script. When it kept getting delayed, in a way it was good, because it meant that I could finish. I find it quite difficult to bounce back and forth and stuff.

As with The World to Come, you spent time on the set of The Brutalist. Is that important to you? And do you feel like you know a lot more about the mechanics of scoring going into this one?

Yeah there is a tendency with films where [music composers] start after the edit. I sometimes get sent films that are already edited. And for me, I just at, least initially, like to make it as fluid as possible. So for me, seeing the shoot, and the space, reading the script, I prefer that as opposed to working to picture. WHat I quite like about doing the scores is that it’s definitely for that story. And you want to create a sonic world, in the same way that Brady is trying to create a visual language with his story. It’s like I’m trying to help him with the audio side of the story.

But yeah, of course The World To Come was the first feature I did, so technically you learn a lot. More about like timings and how it all works, how to plan sessions and stuff. There’s quite a lot of technical stuff to do.

Is there any sense in which scoring a film is more of a “j-o-b”?

I’ve never had that experience. In my life I think there’s been moments when I tried to make, or I tried a couple of times to think about things like, “Oh, maybe I could do this as a job.” But it’s just not how I work.

Would you be capable of creating a visual piece on commission? If someone wanted to pay you a lot of money to create—a mural, say—with certain specifications?

I mean, that’s like saying, “Do you think you could study law and become a lawyer?” I mean, probably if I wanted to spend that amount of time doing something completely random, I could. I’ve never been fishing, for example. But if I wanted to move somewhere and start fishing, I’m sure I could work out how to do it. But it’s just not what I do.

When you start to say, “Can you draw like this?” or something, I just don’t know what that is. I mean I did a thing, like an exhibition at a museum, where my work was too fragile to transfer. It just ended up costing too much. But in the end they said, “Do you just want to come to the museum, and do the work here?” And I did. And they said, “How long do you need?” and I said, “an evening.” And they were really surprised about that, but that’s how I work. I spread out a piece of paper and just do it. But yeah, I don’t get stuff that comes with instructions, if that’s what you mean.

That’s kind of what I meant.

But I don’t think it’s an ethical thing. It’s, again, just the way I work. I like working in different rhythms and stuff, but it depends on who and what the project is.

The “alone time” you had on GUT and your recent live performances of the album—that’s about to come to an end with The Brutalist.

There is a certain kind of focus to the solo thing that I think is important. But yeah, normally it’s kind of mixed in with playing with other people, and I do miss playing with others. Working on a film score, soon people will start coming into that process, yeah. And then I’m working with the director, and that’s very collaborative. It’s nice to have that. But then in a few months I’ll be sick of people. I’ll be sick of everyone coming to the studio with their instruments and stuff. [laughs] You have all these things that you want to do. Sometimes it seems nice to be sitting in the studio, on my own, drawing all day. It sounds really lovely! [laughs] Sometimes you just want to do something else.

You’ve had such a varied life it’s strange sometimes to think you’re still only in your early thirties. But then again with the music you make, it seems you often work with people decades older than you.

I think age is a—I don’t know, it’s a funny thing. My friend just turned 90. When we met, I was like 18 or something, and I didn’t even know how old she was. She must have been like 75? But she was driving around. Now she’s kind of stuck at home, which is sad. But she’s truly one of my closest friends. I knew she was older than me, of course—like 75 to 18 is like a big age gap—but no, I’ve always had people that I work with that, or friends who are different ages.

Or, I like film and lots of older directors’ work, like [Robert] Bresson, he made his last film, L’Argent, it was a masterpiece, at age 82. I think [Michael] Haneke started making films when he was in his mid-forties. And then my friend who’s a painter has just become famous in her 80s, and she’s just still working, like she always does.

I think, maybe with music, with pop music, sometimes there’s an emphasis on youth. But yeah—I definitely have friends who are different ages. I mean, before most of my friends were older than me, but I have a few friends that are younger than me now! [laughs] But that’s what happens when you get a bit older, I guess.

Five things I love about Daniel Blumberg

by John Norris

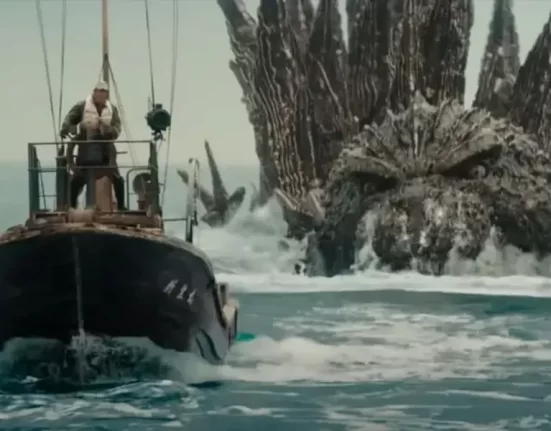

The World to Come (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack): Daniel’s entry into feature scoring came with this sonic accompaniment to Norwegian director Mona Fastvold’s 2020 film starring Vanessa Kirby and Catherine Waterston, about forbidden love in 19th century rural America. Blumberg created the score with veteran Scott Walker producer Peter Walsh, a frequent collaborator; the improvisational work, which includes musicians Peter Brötzman, Josephine Foster, and Steve Noble exquisitely captures the solitude, tension and tenderness of an inspired, original and under-appreciated feminist film. In 2022 Daniel won the Ivor Novello Award for Best Original Film Score for The World to Come.

Café Oto: Read anything about Daniel Blumberg’s creative evolution over the past decade and the name of this experimental music mecca in London will come up. By the time I first visited Oto in 2015 to see Jenny Hval, it was partly a pilgrimage to a spot that I knew had come to loom large for Daniel. A few years later, for his album Minus we talked about the space, his performances there, and his work with Oto regulars including Billy Steiger, Tom Wheatley, Ute Kanngiesser, and saxophonist Seymour Wright, with whom Daniel performs in the duo GUO. For all its 15-year global renown, Oto is a remarkably understated place, but with very special vibes. I highly recommend a visit next time you’re in the vicinity of Dalston.

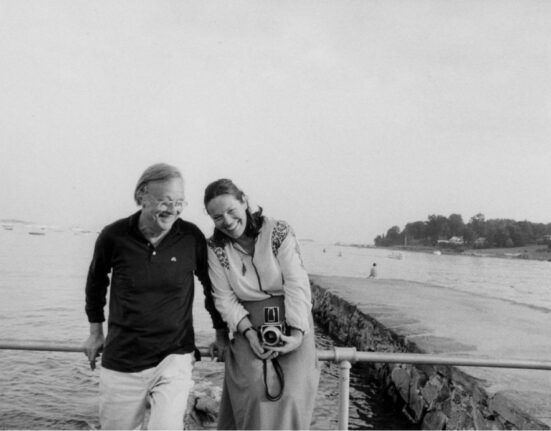

Collaborations: When you talk to Daniel he’s as—or more—interested in heaping effusive praise on the gifted group of creatives in music, film and art he’s been able to work with and learn from for more than 10 years. Apart from the aforementioned folks, there’s filmmaker Peter Strickland, who created a short film for Blumberg and Wright’s 2019 GUO4; writer and director Brady Corbet, who’s collaborated on several projects including his own upcoming feature The Brutalist, which Daniel is scoring; experimental Japanese legend Keiji Haino; and Welsh experimentalist Elvin Brandhi, with whom Daniel plays in the project BAHK—here they are surrounded by parrots and parakeets in 2020’s “We Never Landed.”

“CHEERUP”: Daniel teamed with Corbet for an entire 16mm black and white film for the entire GUT album, and in this first segment, “CHEERUP” released in April, he bares skin, bone and soul in a Brooklyn warehouse. Bathed in shadows and blinking into a harsh light, he plays the bass harmonica and sings a lyric that’s sweet, forlorn, and possibly in need of that titular cheer-up: “Nothing ever changes in this world/ Nothing rearranges, time is slow.” GUT is a powerfully intimate record.

David Toop’s Inflamed Invisible: I feel a little smarter after a conversation with Daniel, who’s an avid reader and film buff, and as his work suggests, is deeply interested in the nexus of sonics and art. That’s at the heart of Inflamed Invisible: Collected Writings on Art and Sound a book he suggested, by the improvisational musician and academic David Toop. It collects four decades of essays, reviews and other writing that offer much to consider about how we think about what we often call “music,” and it’s fascinating stuff.

Yuck’s “Get Away”: Yuck may feel like a lifetime ago for Blumberg, but for the early 2010’s indie rock fan that I assuredly was, the band was fuzzed-out perfection. Their first LP is still, for my money, one of the finest debuts of the millennium, and its opener “Get Away,” a glorious 3:30 marriage of swirly, irresistible riffs and a soaring chorus. Yuck was just a blip, a very early chapter in the story of an artist who only gets more fascinating over time, and the mop top and the riffage are long gone. But “Get Away” will forever remain my gateway drug to Daniel Blumberg.