The Thirty Years’ War, from 1618 to 1648, was one of the most devastating events in European history. Violence, famine and disease killed one-third of the population in central Europe. Still, there was art — created, looted and traded. Art played a role in the war effort itself and in our understanding of the period.

Art and conflict are explicitly linked. It can serve as propaganda or draw attention to the brutality of war: Think Francisco de Goya’s visual protest series, Disasters of War (1810 to 1820), or Pablo Picasso’s iconic Guernica — a response to the April 1937 bombing of the Spanish town.

An ongoing exhibition at Brussels’ House of European History explores this traumatic period in European history through art. Called Bellum et Artes: Europe and the Thirty Years’ War, it brings together about 150 objects — a mammoth project supported by 12 museums and research institutions around Europe.

“It combines intellectual curiosity with aesthetic pleasure,” Andrea Mork, the chief curator, said at the opening in April.

The war’s need for information sparked a media boom. This was the period when the first newspapers emerged, alongside pamphlets and handwritten newsletters containing both disinformation and reporting, some of which are on display.

Warring parties used art as military propaganda. King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, one of the main belligerents in the early part of the war, launched an entire image campaign. His portrait could be found in paintings, pamphlets and on souvenirs. It was used on goblets, too — one of which is displayed at the exhibition.

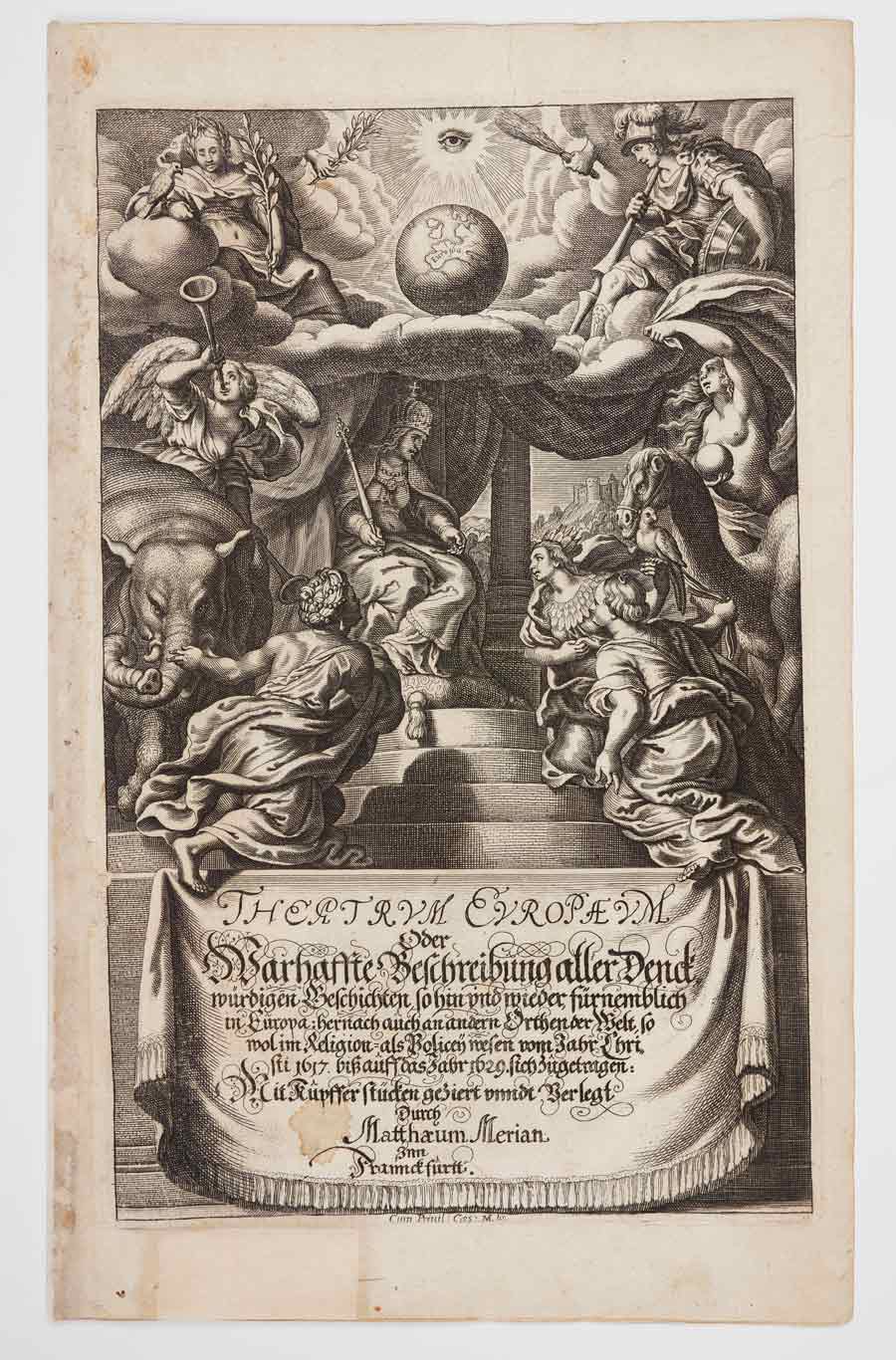

Artwork also appears in illustrated war chronicles. Original copies of the journal Theatrum Europaeum show battle formations and sieges in great detail, such as the First Battle of Breitenfeld in September 1631 by Matthäus Merian the Elder. It is widely considered the most significant work depicting 17th- and early 18th-century European history.

The role of art was not limited to the creation of new works: Existing masterpieces were integral to both wartime finance and diplomacy. Conquests often included large-scale lootings, such as in Heidelberg in 1622 and Prague in 1648. Victors would add valuable artworks and books to their collections, or exchange them for favours, using them as diplomatic gifts. As a result, famous European collections were dissolved and new ones emerged.

The exhibit displays a jug that was part of the silver treasure held on the Spanish fleet captured by Dutch naval commander Piet Heyn near Cuba in 1628. The treasure was then used to fund the Netherlands’ ongoing war against Spain.

Interactive media stations make it possible to retrace the migration routes of both artwork and artists, as collections and artistic treasures were displaced on a regular basis. For example, Leda and the Swan by Andrea del Sarto started in Prague at the war’s outset and made its way through Sweden, Antwerp, Rome and London, before finally ending up in the Royal Collection in Brussels.

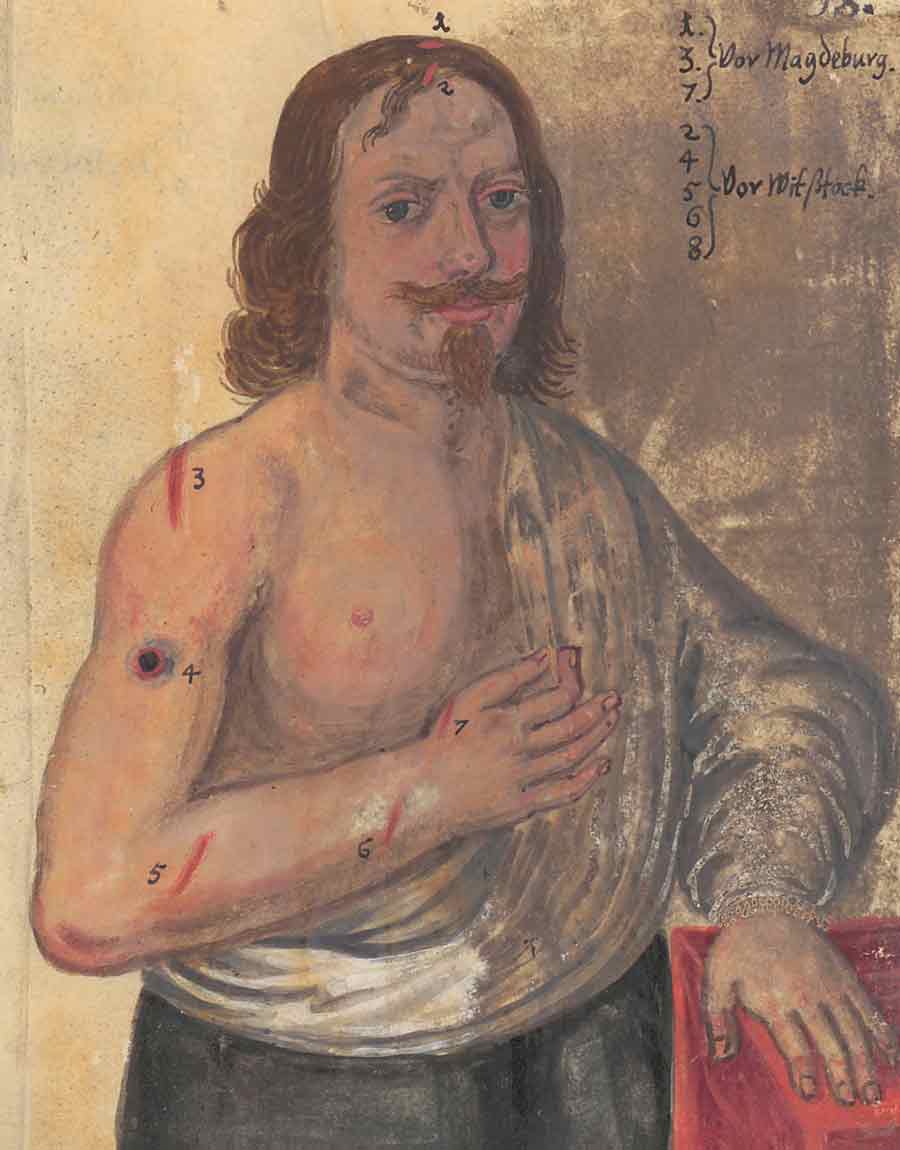

One exhibition room is entirely dedicated to civilian suffering and the horrors of war. Violent attacks, rape and looting by troops on various sides were experiences artists depicted. Sebastian Vrancx’s Soldiers Looting a Farm from around 1620 paints a vivid picture of those atrocities. Daniel Hubatka, a former soldier, detailed his many war injuries in meticulous drawings (1655). Other works show a field doctor examining an injured soldier, or prisoners handcuffed and naked.

The exhibition also highlights the end of hostilities, displaying the peace treaty of Osnabrück, which was ratified by Queen Christina of Sweden on 18 November 1648. It was part of the peace of Westphalia that finally brought the Thirty Years’ War to a close. The bloody experience laid the groundwork for the emergence of European nation states and international law, as set out by Dutch scholar Hugo Grotius. His book, On the Law of War and Peace, is also part of the exhibit.

Bellum et Artes includes a nod to modern-day conflict. A large-scale contemporary piece by Ukrainian artist Vlada Ralko is also on display, representing Russia’s aggression against her native country. Like the exhibit overall, it is further testament to the role that art and artists play in war.

“Bellum et Artes” is on at the House of European History, in Brussels, until 12 January 2025.