Since 2020 Americans have lived through extraordinary sociopolitical events: Black Lives Matter protests erupted across the country in response to the murder of George Floyd; far-right activists stormed the Capitol, incited by Donald Trump’s false claim that the presidential election had been stolen from him; labor organizers Chris Smalls and Derrick Palmer achieved the seemingly impossible task of establishing a union for warehouse workers at the corporate juggernaut Amazon; and Joe Biden’s administration passed the largest federal climate legislation in the country’s history—all while COVID-19 upended millions of lives across the United States.

Though these circumstances might feel unprecedented, in many ways they mirror the conditions that characterized the 1930s. The decade was defined by the Great Depression, which resulted from the stock market crash of 1929—the worst crisis the nation had experienced since the Civil War. While American visual culture has always been suffused with ideology, cultural production in the 1930s represents an exceptional range of political messaging. Widely circulated prints, posters, and magazine illustrations advocated for labor unions and communist and socialist causes; propaganda for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s controversial New Deal solicited support for its relief programs, which were designed to revive the economy; and several world’s fairs communicated values of technological innovation, American imperialism, and capitalism through the work of architects and designers.

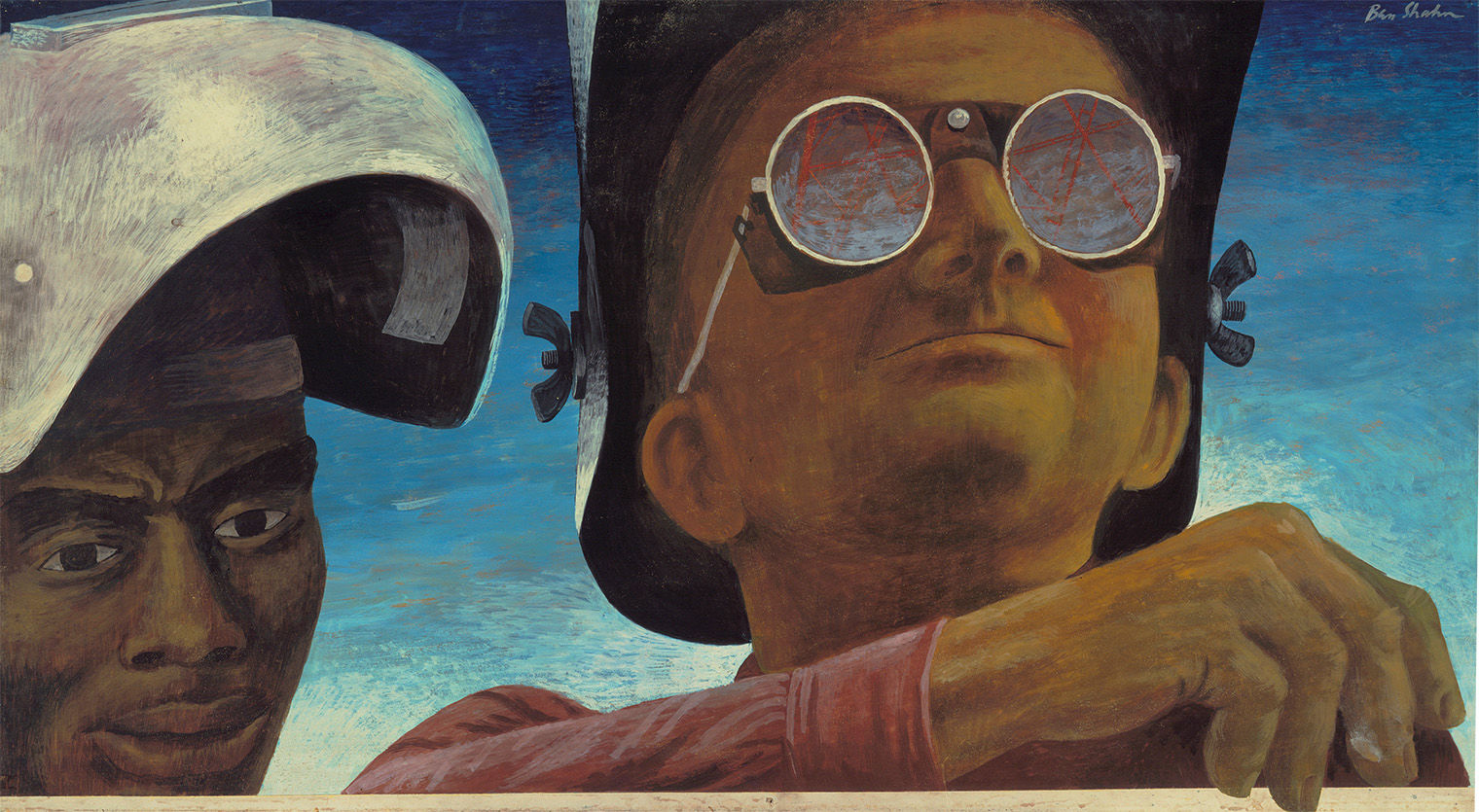

Ben Shahn (American, born Lithuania, 1898–1969). Welders, 1943. Gouache on board, 22 × 393/4 in. (55.9 × 101 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Purchase, 1944

The Works Progress Administration (WPA)—a New Deal agency established in 1935 to bring jobs to the unemployed, including artists—aimed to make and distribute “art for the millions” in order to engineer a more cultured, educated, and refined citizenry. While the exact number of people who encountered the art of the WPA is impossible to measure, it is unquestionable that millions of Americans consumed an array of complex and conflicting political messages between the output of the agency and the broader visual world around them.

Leftist Politics and Labor

At the height of the Depression in 1933, nearly 13 million people—roughly 25 percent of the total workforce—were unemployed. This dire situation ignited a militant labor movement led by organizers with left-leaning politics who drew attention to low pay and harsh working conditions. Artists across the country centered the plight of the proletariat in their work and joined activist groups associated with the American Communist Party (CPUSA) that advocated for better protections for workers.

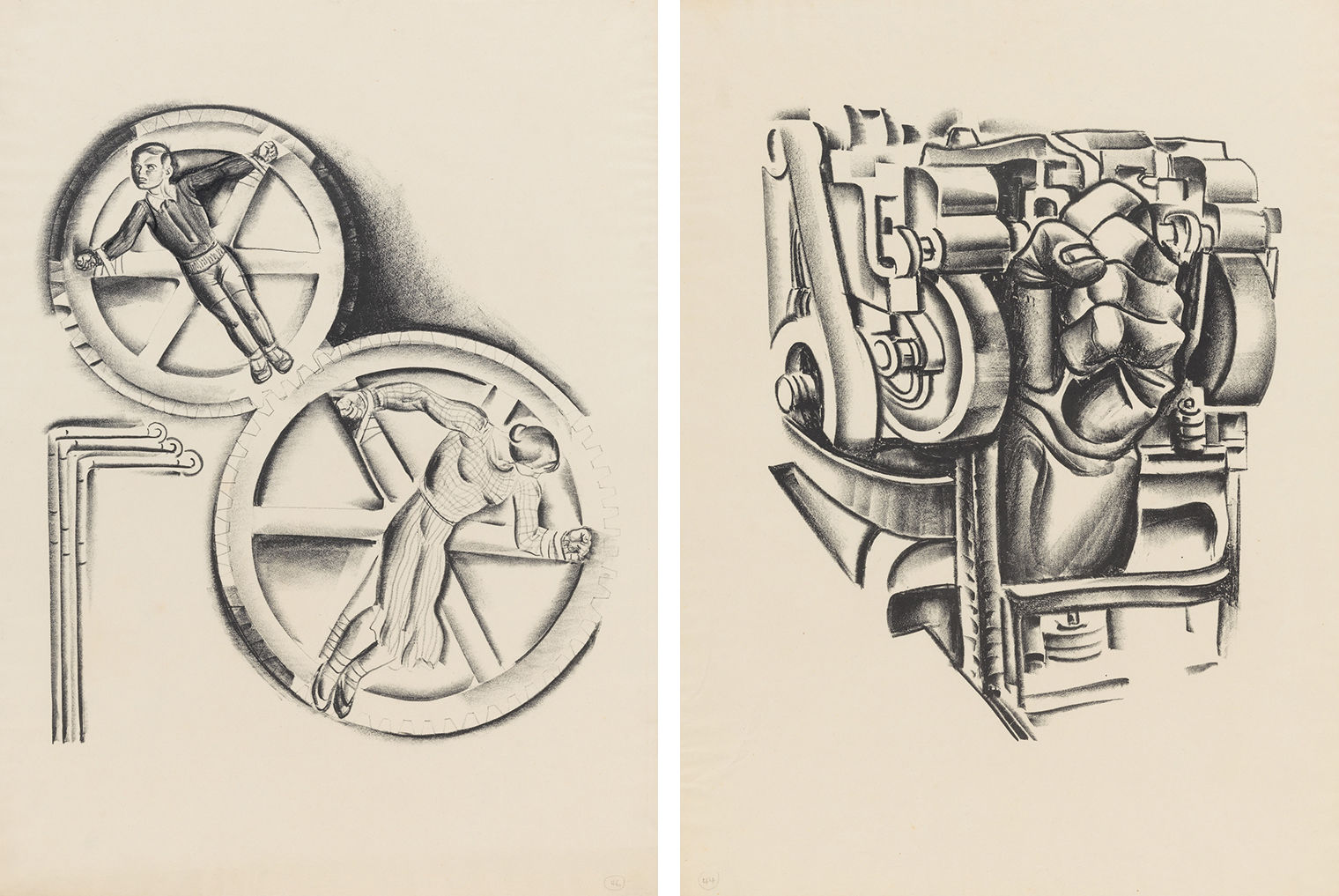

Some artists—particularly a loose group known as the Precisionists, working primarily before the stock market crash—treated industrial machinery and the plants that housed them as objects of fascination and wonder. After the onset of the economic downturn, however, wage workers were placed front and center. Images that pitted industrial machines against people invoked Karl Marx’s theory of exploitation under capitalism, as in communist artist Hugo Gellert’s illustrations for a condensed 1934 edition of Das Kapital. In one, a woman and a young boy are bound at the wrists to oversize cogs in a scene that conjures the Crucifixion, with the vulnerable sacrificed in the name of capitalism. In another, a muscular fist breaks through a mass of mechanical parts, conquering the machine-enemy.

Left: Hugo Gellert (American, born Hungary, 1892–1985). Machinery and Large Scale Industry 46, 1933. Lithograph, 201/4 × 15 in. (51.4 × 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Abner and Miriam Diamond, 1998 (1998.392.5). Right: Hugo Gellert (American, born Hungary, 1892–1985). Machinery and Large Scale Industry 44, 1933. Lithograph, 201/4 × 15 in. (51.4 × 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Abner and Miriam Diamond, 1998 (1998.392.4)

Tens of thousands of artists found work through the Federal Art Project (FAP) and related initiatives that operated under the aegis of the WPA. Communal WPA workshops cropped up across the country, where workshop instructors introduced legions of artists to printmaking. The public encountered these prints at WPA-organized exhibitions, and, as official government property, they were donated to or placed on long-term loan at various museums, libraries, and other public institutions across the United States after the close of the WPA in the early 1940s.

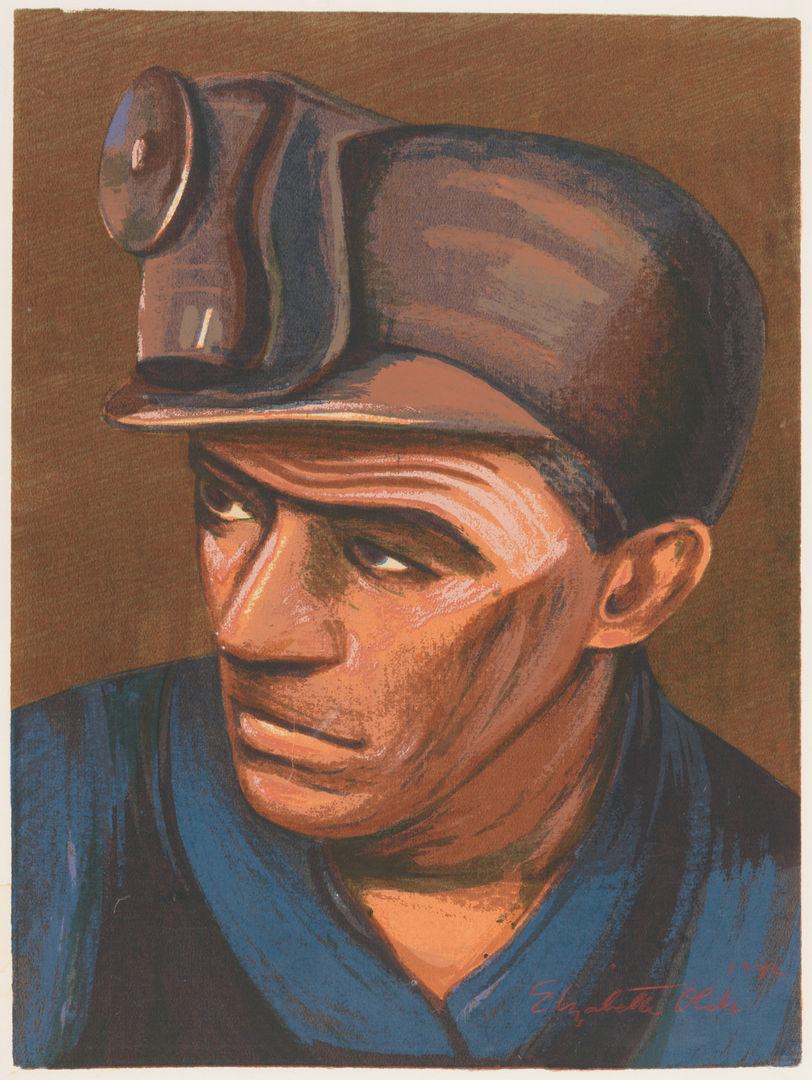

Printmaking became the medium of choice among activist artists due in large part to its capacity for producing multiple impressions of the same image, enabling them to disseminate their political messages to a broader audience. Many WPA prints featured idealized images of people at work and engaged the accessible style and sociopolitical subject matter of social realism. One powerful example is Elizabeth Olds’s screenprint Miner Joe (1942), which depicts a lone figure in a helmet and overalls from the chest up, his head tilted slightly against a bare background. Olds’s focused treatment imbues her subject with an air of dignity and valor.

Elizabeth Olds (American, 1896–1991). Miner Joe, 1942. Screenprint 183/4 × 123/4 in. (47.6 × 32.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Accession, transferred from the Lending Library Collection (64.500.1)

While women and people of color often faced barriers in hiring, visibility, and equal treatment in the art world, the WPA provided many with unprecedented access to art-making and exhibition opportunities. Though aspects of the hiring practices and management of the FAP were also undoubtedly discriminatory, its top administrators made efforts to establish egalitarian environments that could be held up as evidence of its alignment with the Roosevelt administration’s democratic values. Jacob Lawrence spoke fondly of the progress made for artists in the 1930s decades later, at a roundtable discussion titled “The Black Artist in America” convened at The Met in response to the backlash against its controversial 1968 exhibition Harlem on My Mind. He described it as a time when “we’ll find that some of the greatest progress, economic, professional, and so on, was made . . . by the greatest number of artists—not only Negro artists but white ones as well. The greatest exposure for the greatest number of people came during this period of government involvement in the arts.”

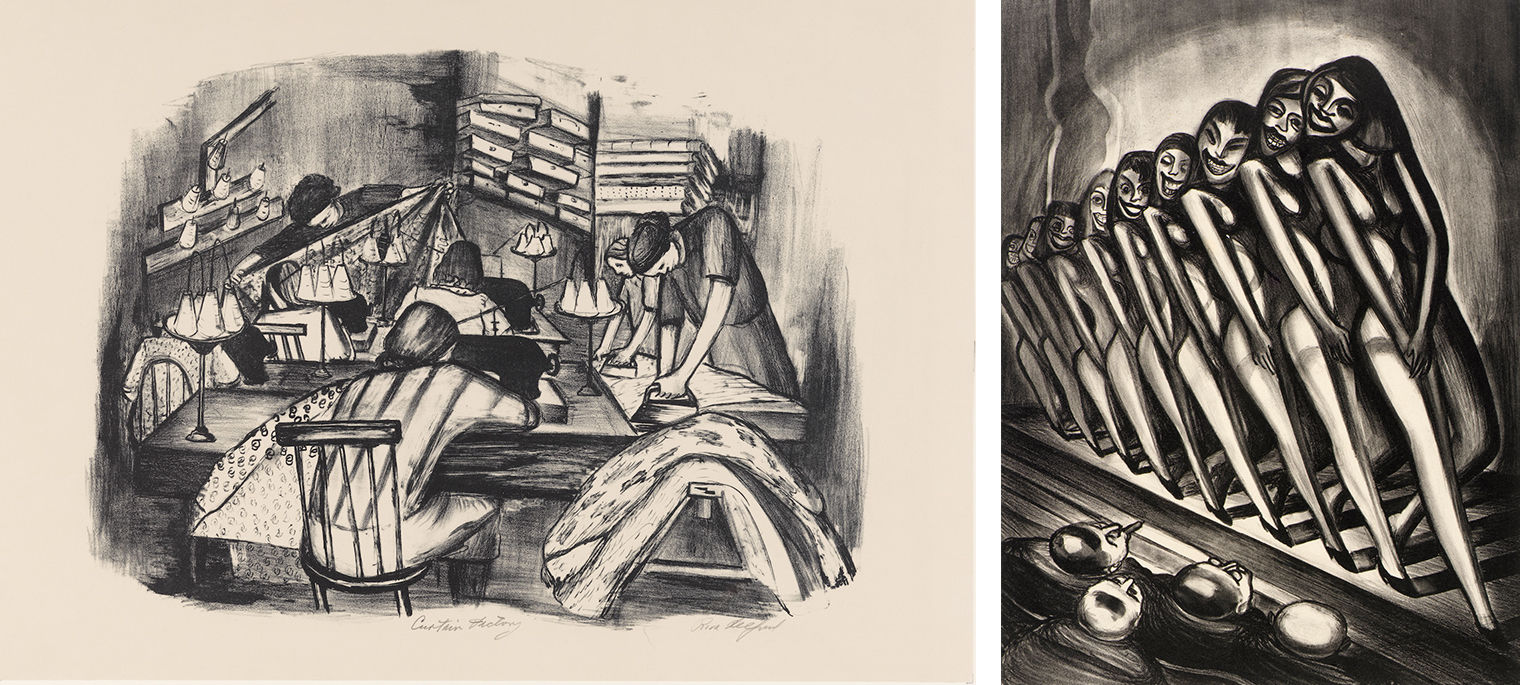

Despite the increased presence of women in the arts, images focusing on women’s paid labor were scarce. Riva Helfond was a seasoned printmaker when she joined the WPA, first as an instructor at the Harlem Community Art Center and later as an artist in the Graphic Arts Division of the New York City FAP. Her print Curtain Factory (ca. 1936–39), which depicts fatigued workers, is a rare example. She had worked in textile factories and experienced firsthand the physical strain of the work, conveyed here through the downward curves of the workers’ bodies. Although scenes of women performing in cabarets and clubs were common, few artists approached them from the perspective of feminized labor. One exception is Olds, whose Burlesque (1936) presents the bodies of female performers on stage in a serialized formation that conjures an assembly line while male viewers gaze longingly from below.

Left: Riva Helfond (American, 1910–2002). Curtain Factory, ca. 1936–39 Lithograph, 141/4 × 201/2 in. (36.2 × 52.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of New York City WPA, 1943 (43.33.694). Right: Elizabeth Olds (American, 1896–1991). Burlesque, 1936. Lithograph, 141/2 × 1013/16 in. (36.8 × 27.4 cm) Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the Lola Downin Peck Fund from the Carl and Laura Zigrosser Collection, 1981

While laborers of color were frequently depicted alongside white ones in prints by white artists, prints centering workers of color are rare. One reason for this scarcity likely relates to the persistence of racial discrimination in the workforce and the labor unions that emerged as a major presence in the thirties. Workers of color came up against numerous barriers, from discriminatory hiring processes to being denied adequate training or educational opportunities; they were also often denied union membership. Dox Thrash, one of the era’s most prominent and innovative Black printmakers, was characterized as staunchly anti-union by his fellow workshop artist Claude Clark. But Thrash also experienced the effects of labor discrimination throughout his career, having been shut out of so-called skilled positions until he was employed by the FAP—experiences that might have reinforced his opposition to the labor movement.

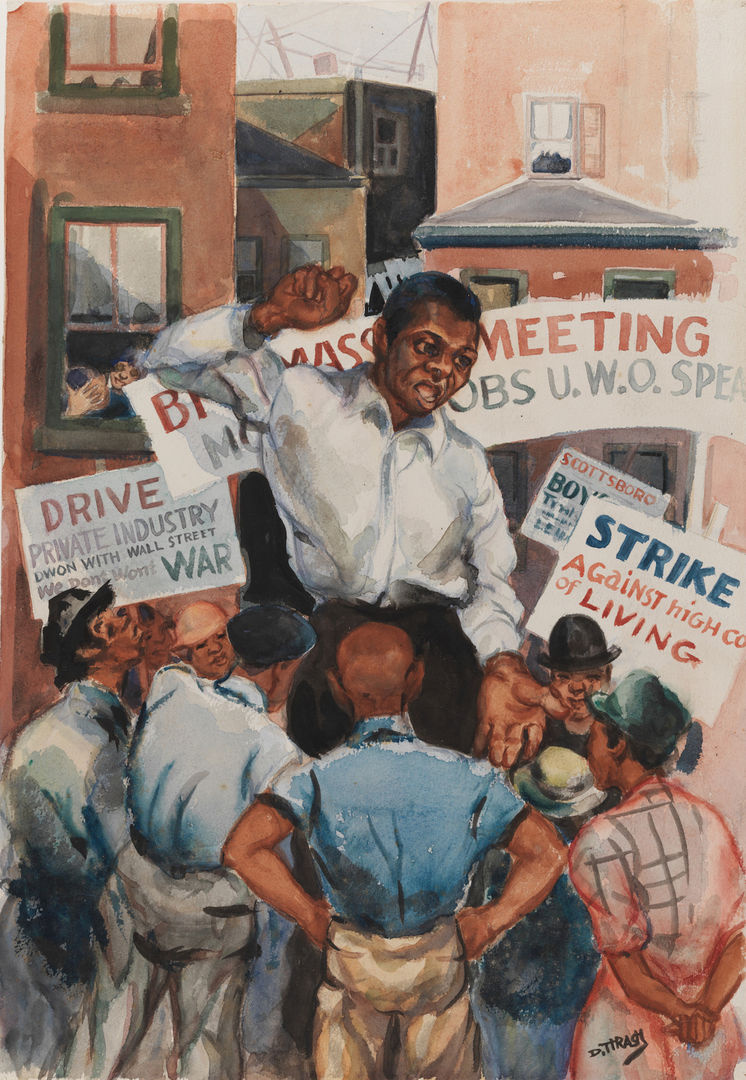

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). Untitled (Strike), ca. 1940. Watercolor, 171/8 in. × 12 in. (43.5 × 30.5 cm). Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Museum Purchase

Whatever his political leanings, Thrash depicted scenes of leftist activity, as in Untitled (Strike) (ca. 1940), a watercolor rendering of a Black organizer surrounded by a crowd of figures carrying protest signs. A placard to the organizer’s left references the landmark Scottsboro Boys trial, in which nine Black youths were falsely accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931. To his right, a man and a woman peer out of the window of a nearby building; the woman laughs as she looks toward the man, who covers his face with his hand—a gesture that may have reflected Thrash’s own feelings toward the labor strike.

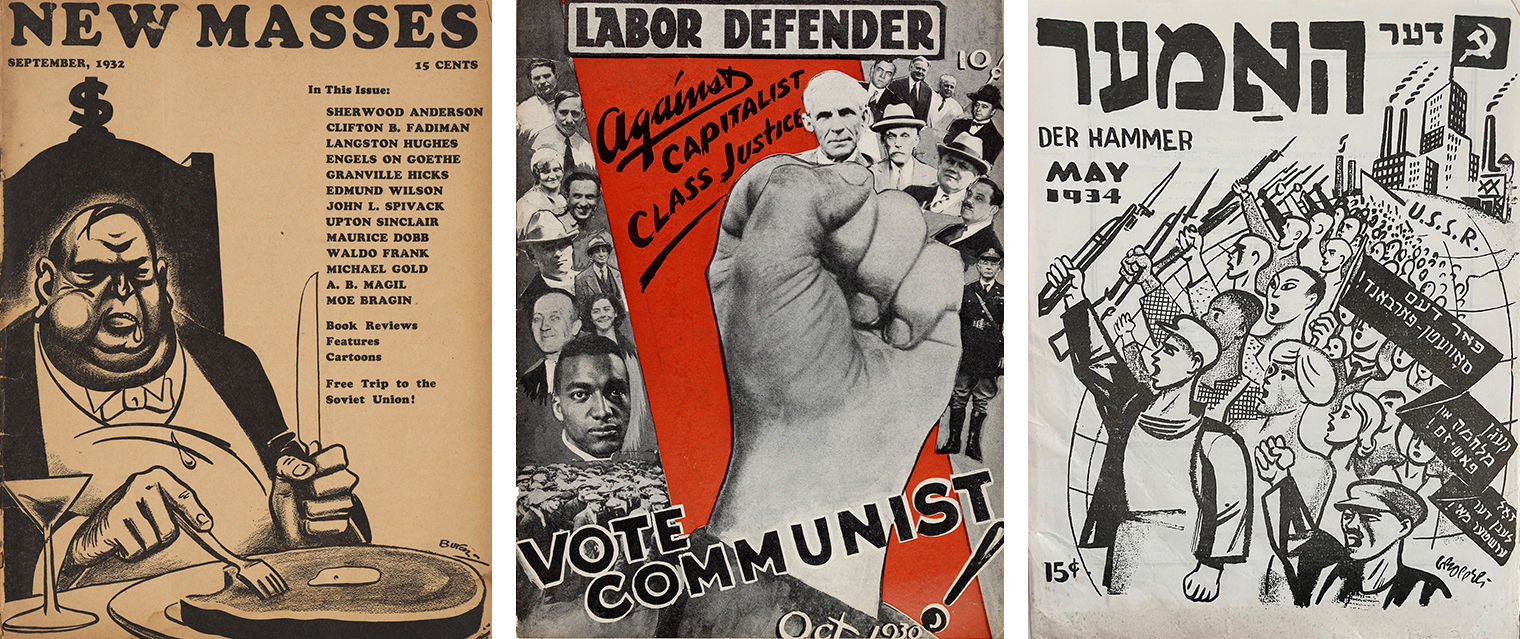

Communist newspapers, magazines, and journals offered artists opportunities to advance their messaging through vivid illustrations. The communist periodical New Masses incorporated the visual arts in its pages more than any other leftist publication of the period; in addition to political cartoons and drawings, the magazine reproduced social realist prints and paintings whose themes were aligned with its messaging. One particularly memorable cover by Jacob Burck presents a caricature of a capitalist—an embodiment of the worker’s opposition—who drools onto his rounded stomach as he prepares to consume a large steak and a martini, signaling the radicals’ association of capitalism with gluttony and greed. From 1929 to 1931 the masthead credited the artists alongside the writers as “contributing editors,” with prominent figures such as Stuart Davis, Adolf Dehn, Gellert, Louis Lozowick, and John Sloan helping to shape the magazine’s content.

Left: Cover by Jacob Burck (American, born Poland, 1904–1982). New Masses, September 1932. Photomechanical relief print, 111/2 × 83/4 in. (29.2 × 22.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of Drawings and Prints Gifts, 2022 (2022.120). Middle: Labor Defender, October 1930. Photomechanical relief print, 121/8 × 91/8 in. (30.8 × 23.2 cm). Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Right: Cover by William Gropper (American, 1897–1977). Der Hammer, May 1934. Photomechanical relief print, 9 15/16 × 7 5/8 in. (25.2 × 19.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 2023 (2023.188)

New York, where New Masses and other prominent communist publications were based, was home to a thriving community of Yiddish-speaking Jews with leftist political leanings. The monthly magazine Der Hammer (“The Hammer”) often featured political cartoons by William Gropper, a Jewish artist born to Romanian and Ukrainian immigrants. Gropper was instrumental in forging a graphic, easily legible style that celebrated the proletariat and condemned capitalism—often equating it with fascism—in illustrations targeted at a Yiddish-speaking audience. For radical artists such as Gropper, the press served as a vital means for the dissemination of their work, enabling it to reach a larger public beyond the confines of museum and gallery walls.

Cultural Nationalism(s)

For many facing unprecedented hardship, their American identity offered solace and provided a sense of belonging and pride in democracy. In the cultural sector, this wave of nationalism took the form of a question: What exactly is “American” about American art? Artists and other cultural practitioners sought to define the contours of an art tradition that was specific to the United States and distinguished from that of anywhere else—particularly Europe. Paintings, sculptures, photographs, prints, dances, films, garments, and decorative art objects evoked the American landscape, depicted themes from the country’s history, and reflected the traditions of the innumerable ethnicities represented in the population.

Modernist artists sought inspiration in craft traditions of the United States in order to create a distinctly American mode of art. Charles Sheeler was an avid collector of antique American furniture, which he began incorporating into his paintings beginning in the late 1920s. In Americana (1931), one in a series of seven paintings depicting the interior of his home in South Salem, New York, Sheeler harnessed and accentuated the pared-down, minimalist designs of his furniture to create a modernist composition marrying flat, unmodulated planes of color with striking abstract patterns.

Charles Sheeler (American, 1883–1965). Americana, 1931. Oil on canvas, 48 × 36 in (121.9 × 91.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edith and Milton Lowenthal Collection, Bequest of Edith Abrahamson Lowenthal, 1991 (1992.24.8)

Georgia O’Keeffe similarly looked to craft traditions of the United States while living in northern New Mexico. Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue (1931), one of the first of numerous paintings based on animal bones the artist encountered and collected in the region, contains several references to the Indigenous peoples of the Southwest. The cow skull resembles the animal masks worn by the Pueblo people in ceremonial dances; its protruding horns also recall the crosses that decorate the Hispano Catholic churches of northern New Mexico. The abstracted, undulating composition conjures Navajo blankets found throughout the region, and the color palette evokes the American flag—explicitly connecting the practices and products of the Indigenous cultures of the Southwest to an American art tradition.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887–1986). Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue, 1931. Oil on canvas, 397/8 × 357/8 in. (101.3 × 91.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1952 (52.203)

While O’Keeffe’s paintings were firmly grounded in the cultures of northern New Mexico, the lack of figures and concrete references to the region’s inhabitants, coupled with the artist’s “priestess of the desert” persona, perpetuated the idea that the Southwest was an untouched, secluded region. Scholar Patricia Marroquin Norby attributes this perception to the omission of the experiences of O’Keeffe’s Native American and Hispano neighbors in her work, despite career success predicated on their contributions and support. Read within this context, the merging of Indigenous Southwest and nationalist American identities performed in Cow’s Skull points to the ways in which the search for an “authentic” national arts tradition often occluded the perspectives of marginalized groups.

What exactly is “American” about American art?

Tonita Peña (Quah Ah; Cochiti Pueblo, born San Ildefonso Pueblo, 1893–1949). Pueblo Parrot Dance, ca. 1935 Gouache over graphite on wove paper, 14 × 22 in. (35.6 × 55.9 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Corcoran Collection, Gift of Amelia E. White. Published with the permission of Joe Herrera Jr. on behalf of the Peña family

Another successful Pueblo artist of the period was Velino Shije Herrera (Ma Pe Wi), from Zia Pueblo, who was hired by the School of American Research in Santa Fe to create paintings of Pueblo ceremonies. Along with Peña, he became a major figure in the development of the watercolor movement, creating works that feature Pueblo subjects in which the figures—for instance, men on horseback hunting deer—are rendered in meticulous detail against a neutral background. Peña and Herrera exemplify the negotiations many Native American artists made between adhering to longstanding modes of art production and adapting aspects of their practices to appeal to the tastes of European American collectors during the 1930s.

The interest in the Southwest among artists and collectors was part of a larger trend of locating an “authentic” American art tradition in the landscapes and cultures of locales outside major metropolises. The Regionalists—of whom Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood are the best known—claimed the rural, agrarian terrain as well as the inhabitants of the Midwest as subjects evocative of American values of hard work, self-reliance, and simplicity. Their stance that the Main Streets of small-town America constituted the “real” America presaged the rhetorical refrains of present-day politics on both the left and right.

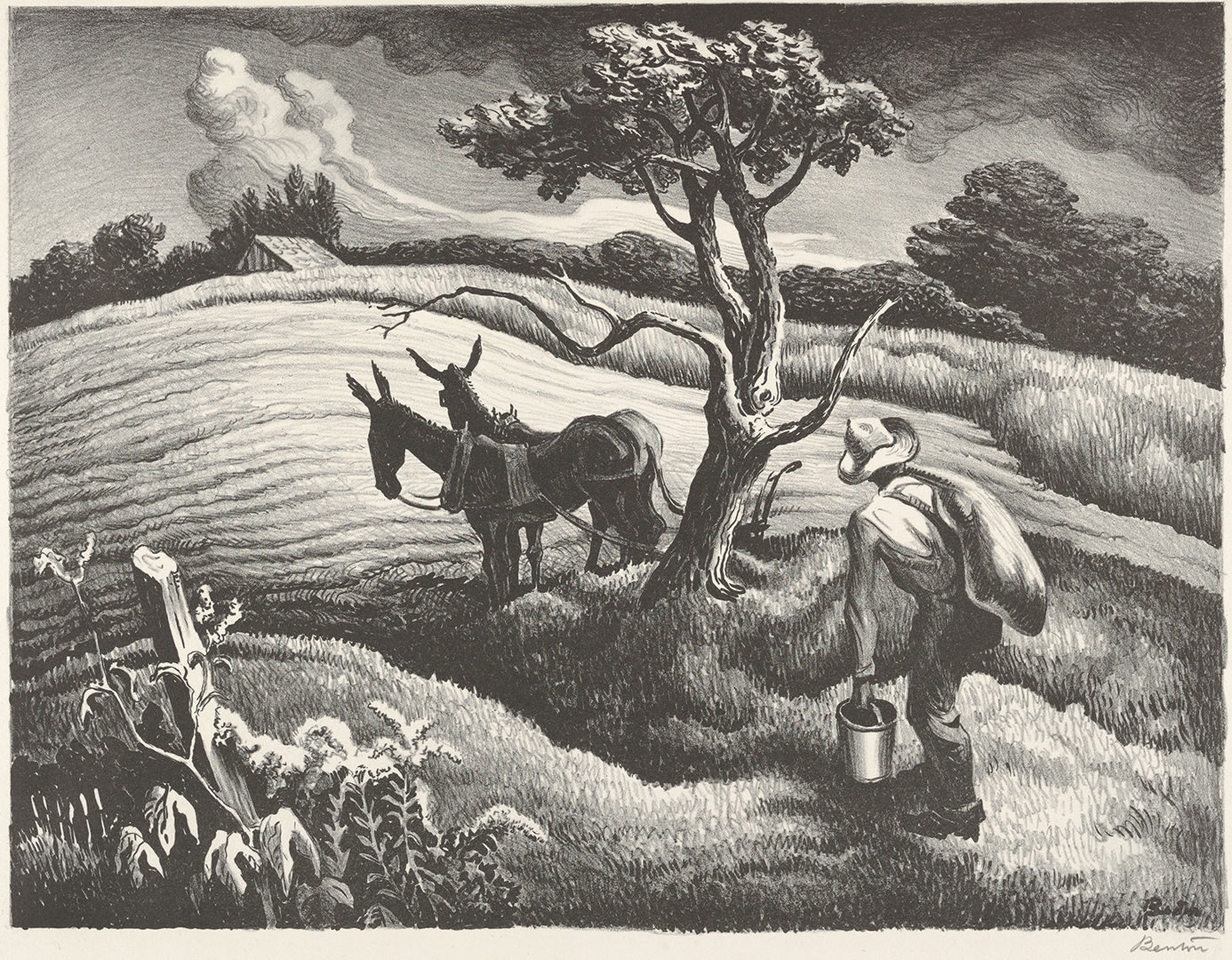

Thomas Hart Benton (American, 1889–1975). Approaching Storm, 1940 Lithograph, 113/4 × 16 in. (29.8 × 40.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Anonymous Gift (42.110.4)

Stylistically, the Regionalists tended to work in an easily legible manner marked by fluid compositions and dynamically posed figures. Many were commissioned to create prints for organizations that strove to make fine-art collecting accessible to the middle class and expand the market for American art, such as the Associated American Artists (AAA), which sold prints at accessible price points primarily through mail-order campaigns, at department stores, and at its galleries. The AAA and regional print clubs contributed to an interest in modernism and the dissemination of Regionalist ideology, with its association of American values with images of the heartland, to a large swath of the public. Benton’s Approaching Storm (1940) was commissioned by the Print Club of Cleveland, which distributed impressions of the lithograph to its members in 1940. Here, in an image typical of the artist’s mature work, a farmer glances up toward the dark roiling clouds in the sky as he makes his way home, barely visible in the distance.

Whose American Story?

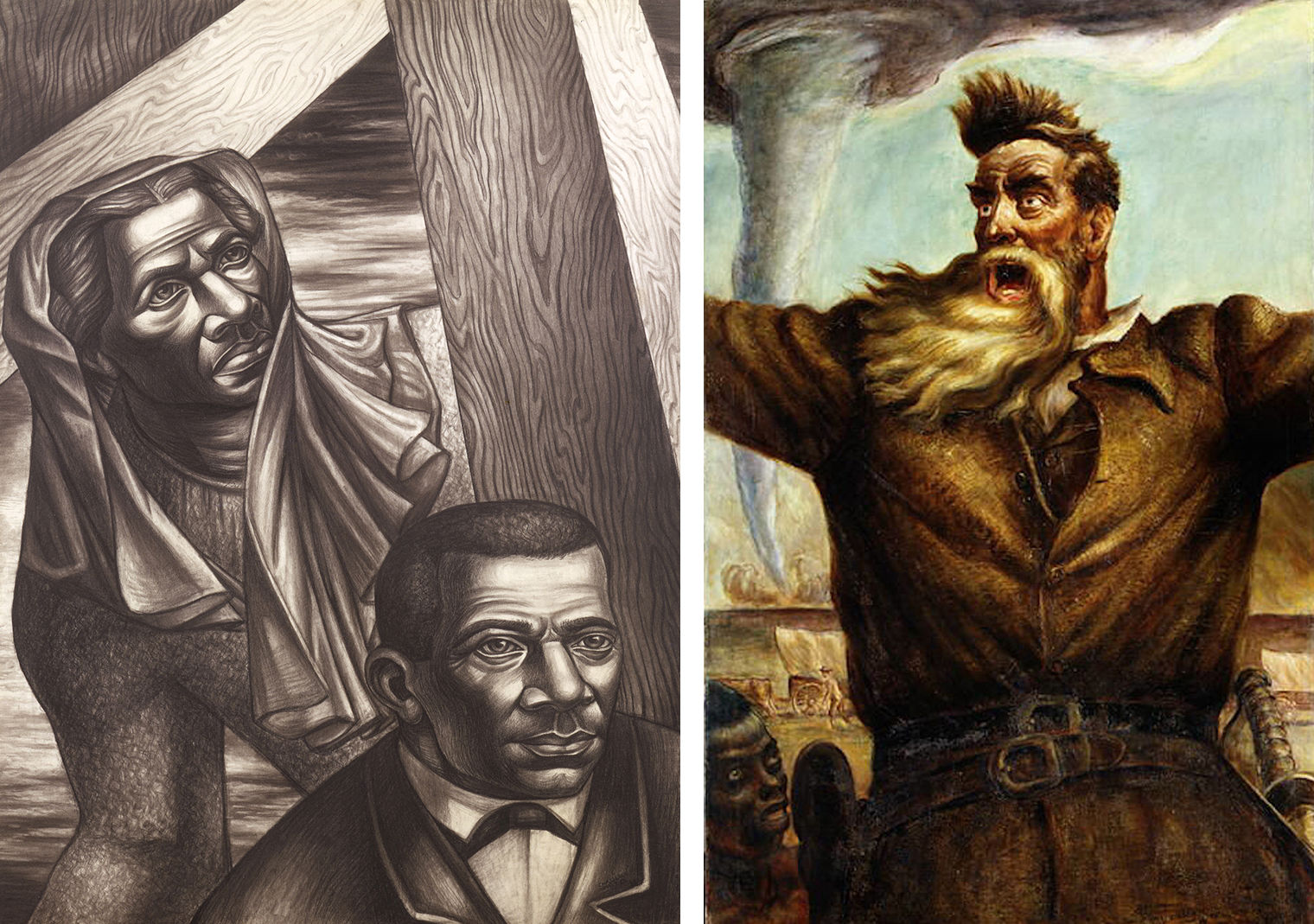

In their efforts to forge a national arts tradition during a time of upheaval, artists also turned to heroes and events from U.S. history to which they ascribed ideals of democracy and freedom. One example is the nineteenth-century white abolitionist John Brown, whose image permeated the art world of the 1930s. Curry honored him in a monumental painting, which served as a preparatory work for a mural in the rotunda of the Kansas State Capitol, as well as a print commissioned by the AAA, further cementing the image’s iconic status.

Left: Charles White (American, 1918–1979). Sojourner Truth and Booker T. Washington, 1943. Graphite on paperboard, 375/8 × 28 in. (95.6 × 71.1 cm). The Newark Museum of Art, N.J., Purchase, 1944, Sophronia Anderson Bequest Fund. Right: John Steuart Curry (American, 1897–1946). John Brown, 1939. Oil on canvas, 69 × 45 in. (175.3 × 114.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1950 (50.94.1)

Charles White sought to lay the groundwork for a more inclusive narrative of the nation’s history by centering the contributions of Black Americans. In 1942 he received a fellowship to make The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America for the Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Virginia. The mural was one of four on aspects of African American history that the painter worked on between 1939 and 1943. In conceiving the mural’s composition, White conducted thorough research on significant historical Black leaders of abolition, resistance, and cultural uplift, including Sojourner Truth and Booker T. Washington. The mural’s political resonance and arrangement of layered and overlapping figures were most directly inspired by the work of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, commonly known as los tres grandes—“the big three”—of the Mexican muralism movement that began in the early 1920s.

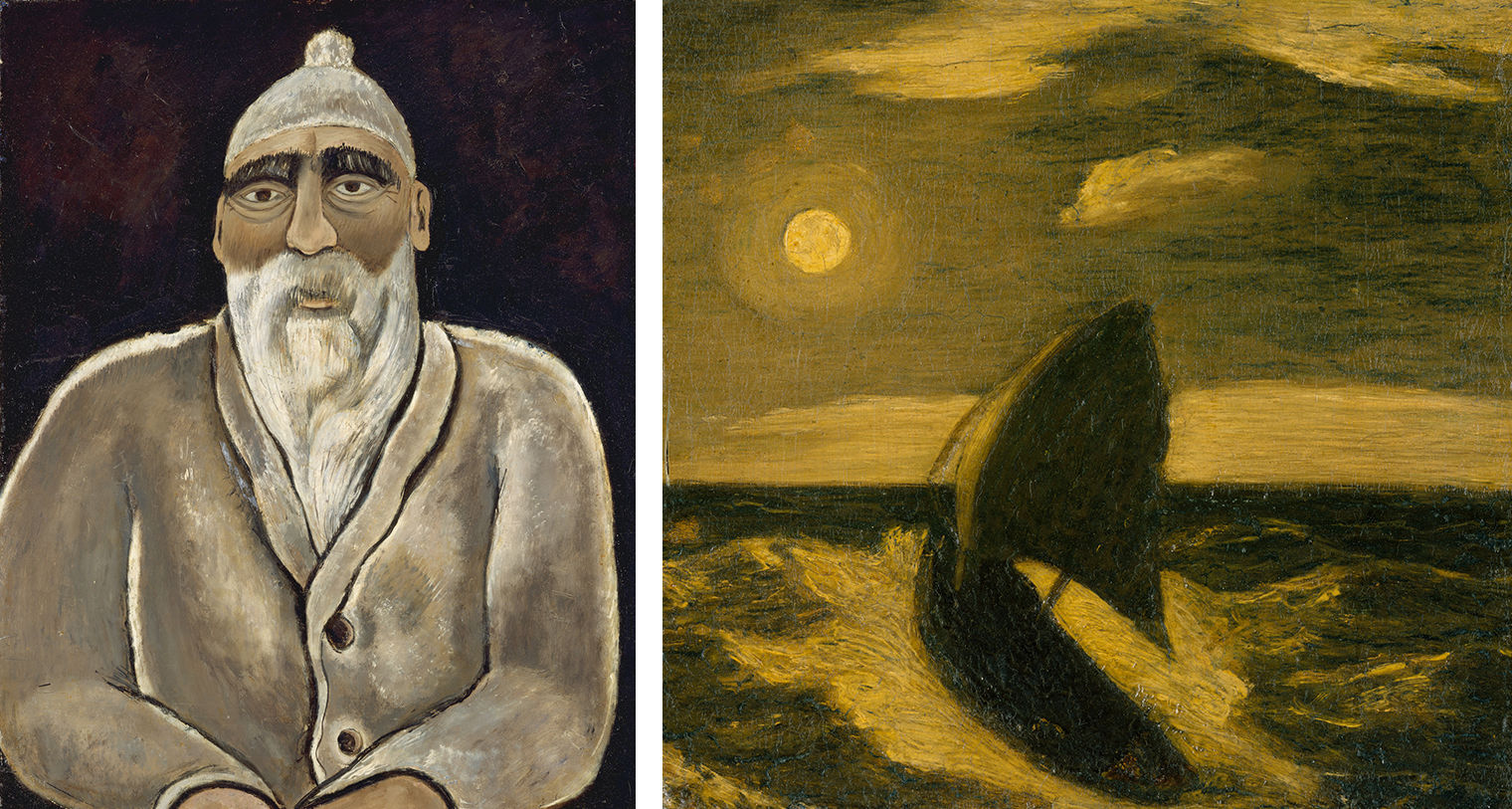

Marsden Hartley was keen to commemorate people who made an impact on the country’s cultural heritage, particularly as he reflected on his own artistic influences toward the end of his career. His 1938 portrait of Albert Pinkham Ryder speaks to the preoccupation of American artists of the 1930s with those of earlier generations; Ryder had garnered a reputation for being a mystic-like hermit during his lifetime and was revered by younger artists such as Hartley, who credited him with developing a distinctly American approach to landscape painting, characterized by a dark, moody palette, abstracted forms, and thick impasto surfaces. Hartley’s tender portrait, which is based on an encounter with Ryder in New York several decades early, evokes the imagery of religious icons, with the figure of Ryder seeming to glow against a dark background.

Left: Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943). Albert Pinkham Ryder, 1938. Oil on commercially prepared paperboard (academy board) 28 × 22 in. (71.1 × 55.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edith and Milton Lowenthal Collection, Bequest of Edith Abrahamson Lowenthal, 1991 (1992.24.4). Right: Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847–1917). The Toilers of the Sea, 1880–85. Oil on wood, 11 1/2 x 12 in. (29.2 x 30.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, George A. Hearn Fund, 1915 (15.32)

Documenting the United States

Some of the most celebrated images of the 1930s were not the sentimentalizing, romantic visions of the past and present that permeated the visual culture of the period but rather ones that captured everyday life. Photojournalism was reinvigorated with the introduction of the photo essay, which was meant to present impartial reportage of newsworthy events. At the same time, documentary-style photography representing a more subjective viewpoint experienced a resurgence thanks in large part to Roy Emerson Stryker, who headed the photography program of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a New Deal agency that combated poverty in rural areas. Stryker hired Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, and others to photograph the communities served by the FSA with the aim of promoting the agency’s raison d’être and persuading the masses of its importance.

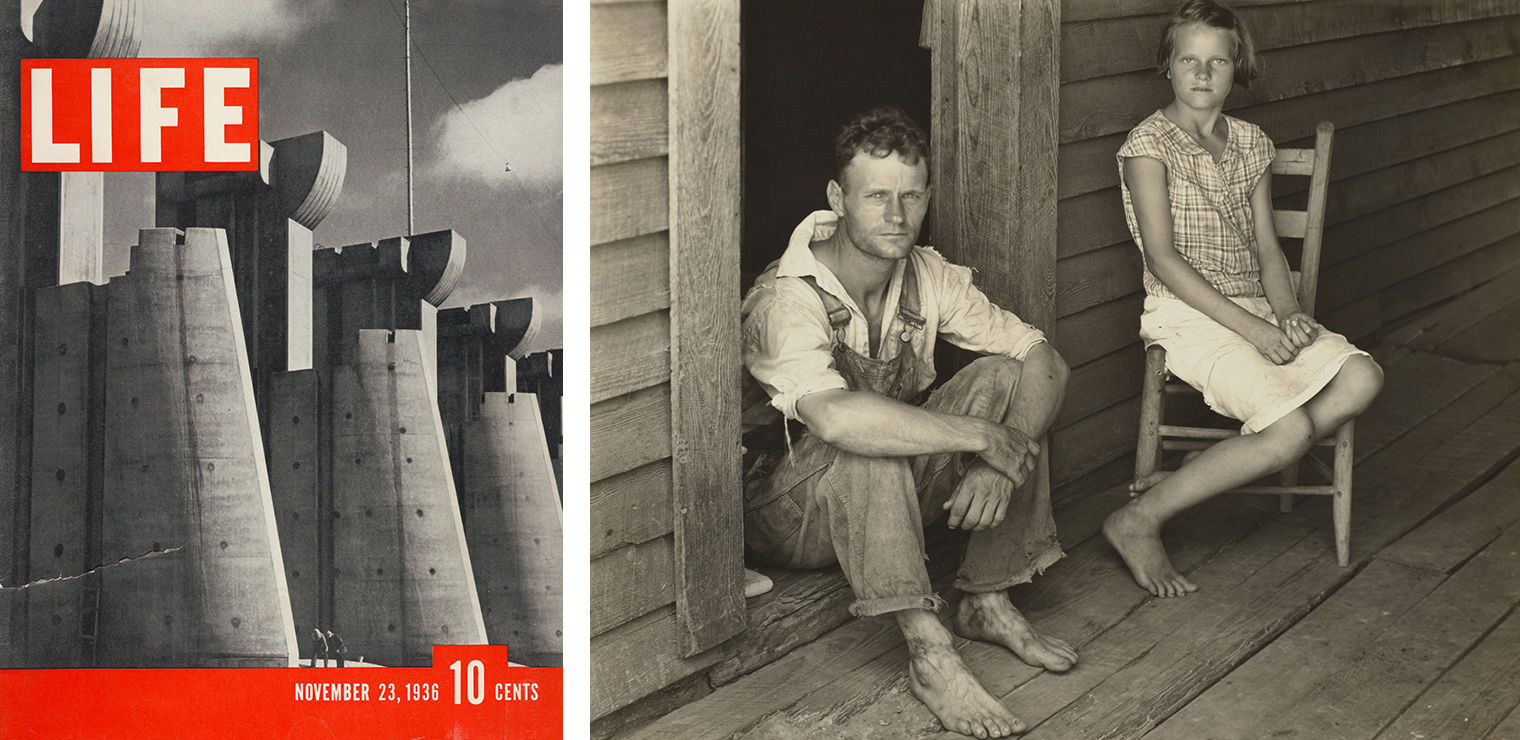

The impact of the photo essay is the subject of an editors’ note in the first issue of Life magazine in 1936. Referring to Margaret Bourke-White’s photograph of the newly constructed Fort Peck Dam in Montana that graced the cover and others by her that captured construction along the Columbia River, they wrote, “What the Editors expected—for use in some later issue—were construction pictures as only Bourke-White can take them. What the Editors got was a human document of American frontier life which, to them at least, was a revelation.” Bourke-White was, notably, the highest-paid photographer of the era.

Left: 1936 cover of Life magazine with a photo by Margaret Bourke-White. Right: Walker Evans (American, 1903–1975). Floyd and Lucille Burroughs on Porch, Hale County, Alabama, 1936. Gelatin silver print, 77/16 × 95/16 in. (18.9 × 23.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Marlene Nathan Meyerson Family Foundation Gift, in memory of David Nathan Meyerson; and Pat and John Rosenwald and Lila Acheson Wallace Gifts, 1999 (1999.237.4)

While Bourke-White celebrated American technological ingenuity in her photographs, documentary photographers often used their camera as a tool to instigate social change. Many of Evans’s most celebrated images were for Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), a book he made in collaboration with James Agee, who had been assigned to write an article on cotton tenant farming by Fortune magazine. The two friends traveled around the South in 1936, with Evans creating arresting photographs of the farmers and their families, such as the Burroughs, whom he encountered in Hale County, Alabama. The editors at Fortune stipulated that Evans photograph white farmers only, despite the fact that the vast majority of tenant farmers in the South were Black.

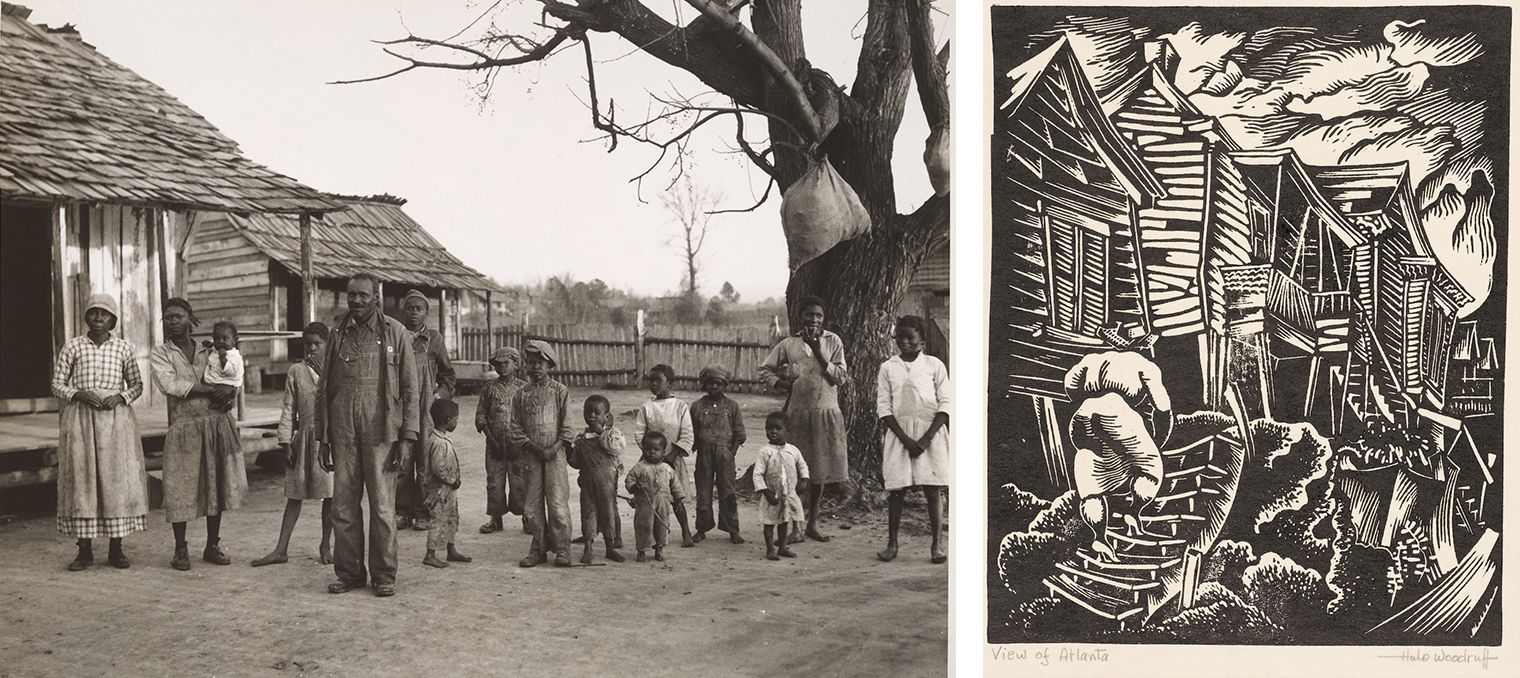

Left: Arthur Rothstein (American, 1915–1985). African American Family at Gee’s Bend, Alabama, 1937. Gelatin silver print, 71/8 × 91/2 in. (18.1 × 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2001 (2001.298). Right: Hale Woodruff (American, 1900–1980). View of Atlanta, 1935 Linocut, 97/8 × 8 in. (25.1 × 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 1999 (1999.529.201)

In contrast to Fortune, the FSA sent Rothstein to photograph the African American sharecropping community of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, in 1937, which resulted in a series of striking portraits. In one, which was later reproduced in Richard Wright’s 12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States (1941), the members of a large family representing a range of ages stand on the site of the former plantation. Perhaps because more Black artists were accepted into New Deal printmaking workshops than into its photography programs, the prints of the period offer more scenes showing the widespread poverty of Black communities in the South during the Jim Crow era than its photographs. One extraordinary example is Hale Woodruff’s linocut View of Atlanta (1935), made while the artist worked for the WPA. It depicts a woman climbing a rickety set of stairs before a row of dilapidated houses. Despite the precarity of the architecture around her, she exudes a sense of sturdiness and determination as she ascends the stairs in a pair of high-heeled shoes.

The Promise of Progress

Even, or especially, as the Depression engendered a period of unprecedented financial strife, the promise of progress infiltrated American culture. This fixation with the United States’ technological and industrial prowess is most evident in the period’s prevailing design trends. In the fields of graphic, industrial, and architectural design, stylistic approaches, techniques, and materials were imbued with values of innovation and modernization. Everyday people experienced these new visual modes through the posters they encountered on the streets, the magazines they read, the domestic and decorative art objects that adorned their homes, and the buildings in which they lived, worked, and shopped. The dissemination of a new, futurist aesthetic among the masses was not accidental but rather part of a larger ideological program intended to “elevate” the tastes of middle-class people, in much the same way that the government sought to give rise to a more cultivated citizenry through exposure to art produced under the WPA.

Designed by Gilbert Rohde (American, 1894–1944). Manufactured by the Herman Miller Furniture Company, Zeeland, Mich. Electric clock, ca. 1933. Chrome-plated metal and glass 121/8 × 121/2 × 31/2 in. (30.8 × 31.8 ×8.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John C. Waddell Collection, Gift of John C. Waddell, 2000 (2000.600.15)

Arguably the most influential trend to emerge in the United States in the thirties was streamline, a style developed by the country’s first generation of industrial designers. Streamlined design has commonalities with Art Deco, which originated in Europe, but differs in its emphasis on speed. The industrial materials of glass and chrome in an electric clock that Gilbert Rohde designed for Herman Miller are quintessentially streamlined, as is the evocation of dynamic movement in the dramatic diagonal thrust of its support. While Art Deco marked architecture, housewares, and jewelry, streamlining was applied primarily to the mass-produced industrial products that emerged in the late twenties.

Left: Designed by Norman Bel Geddes (American, 1893–1958). Manufactured by Emerson Radio and Phonograph Corp., NewYork “Patriot” radio, ca. 1940. Catalin 8 × 11 × 51/2 in. (20.3 × 27.9 × 14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John C. Waddell Collection, Gift of John C. Waddell, 2001 (2001.722.11). Right: Designed by Isamu Noguchi (American, 1904–1988). Manufactured by Zenith Radio Corporation, Chicago; Kurz-Kasch, Inc., Dayton, Ohio; and Chicago Molded Products Corporation “Radio Nurse” monitor, 1937. Bakelite and cellulose acetate 8 × 61/2 × 61/2 in. (20.3 × 16.5 × 16.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John C. Waddell Collection, Gift of John C. Waddell, 2000 (2000.600.14)

Newly invented home radio receivers offered industrial designers an opportunity to package unattractive masses of electronic components into compositions that were appealing and accessible to the consumer public. In 1937 the Zenith Radio Corporation issued “Radio Nurse,” a baby monitor that transmitted sounds from the nursery to a separate receiver called “Guardian Ear,” both designed by Isamu Noguchi. Made of Bakelite dyed a deep brown evocative of wood, the monitor is a domestic product endowed with the look of modernist sculpture. Norman Bel Geddes, one of the founders of the streamlined aesthetic, designed his iconic “Patriot” radio for Emerson Radio Corporation, a leading manufacturer of portable and tabletop radios, around 1940. With its star-engraved knobs, row of horizontal stripes, and red, white, and blue color scheme, “Patriot” encapsulates the convergence of nationalism, technological advancement, and consumerism that marked the era.

Doris Lee’s Catastrophe (1936) provides an explicit yet whimsical indictment of the ambitious race to construct towering buildings and soaring aircrafts. A dirigible has burst into flames above the Manhattan skyline, hovering in the air as figures with parachutes descend onto the banks of the Hudson River. Lee, a painter and successful commercial artist known for her humor and feminist politics, completed this prescient vision just a few months before the Hindenburg disaster. Indeed, a Time magazine article from June 1937 reported that when the artist was painting “the Manhattan skyline last August, she saw the Hindenburg fly over and imagined how it would look if it exploded.” Viewed through the lens of Lee’s feminism, Catastrophe can also be read as a critique of the power-hungry impulses that drove technological advances associated with masculinity. The work also seems to prophesy the tragic extreme to which these impulses would be taken almost a decade later with the introduction of the atomic bomb.

Doris Lee (American, 1905–1983) Catastrophe, 1936. Oil on canvas, 40 × 28 in. (101.6 × 71.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, George A. Hearn Fund, 1937 (37.43)

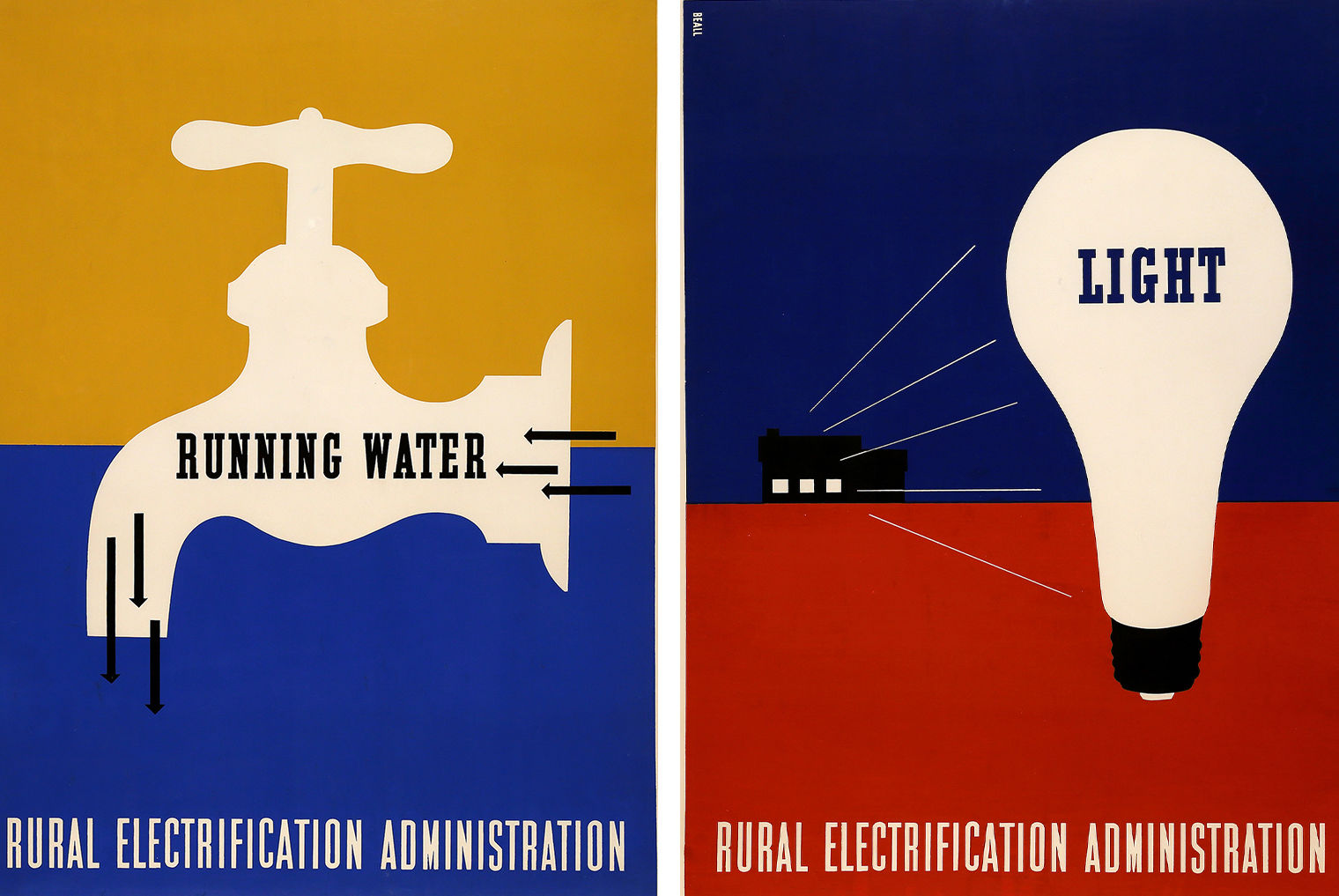

Outside the country’s urban centers, many Americans in agrarian areas were experiencing electricity for the first time. Until 1932 only about ten percent of the rural United States had electricity, and bringing it to the rest of the country became one of FDR’s key infrastructure plans. Rather than build power systems, his administration established the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) to lend funds to electric cooperatives run by local farming communities. The REA hired advisers to travel around the country demonstrating the uses of electricity in what they called “electric circuses,” and artists like Lester Beall to design screenprinted posters to advertise the agency. Following in FDR’s footsteps decades later, President Barack Obama tasked the Rural Utilities Services (which had absorbed the REA) with extending Internet access into rural areas as part of his economic recovery plan following the 2008 recession. Obama invoked aspirational New Deal rhetoric in his statement that the initiative wasn’t “just about a faster Internet or being able to find a friend on Facebook,” but “about connecting every corner of America to the digital age.”

Left: Lester Beall (American, 1903–1969). Rural Electrification Administration, Running Water poster, 1937. Screenprint, 40 × 301/8 in. (101.6 × 76.5 cm). Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, N.Y. Right: Lester Beall (American, 1903–1969). Rural Electrification Administration, Light poster, 1937. Screenprint 397/8 × 301/8 in. (101.3 × 76.5 cm) Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, N.Y.

The world’s fairs of the 1930s celebrated American exceptionalism through spectacle. At the Chicago fair of 1933–34 and New York fair of 1939–40 alone, roughly eighty million visitors experienced patriotic propaganda in exhibitions, at performances, and through fair ephemera. As historian Robert W. Rydell has elucidated, governments have historically mounted world’s fairs and expositions during moments of upheaval, and the fairs of the thirties were no exception. The vast funds and resources that the government and corporate sponsors poured into these events were a vote of faith in their ability to boost public morale.

Left: Published by Interborough News Company, New York. Printed by C. T. Art-Colortone, Chicago. Parachute Jump, New York World’s Fair postcard, 1939. Offset lithograph 51/2 × 39/16 in. (14 × 9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (Burdick 435, PC225-6.39). Middle: Weimer Pursell (American, 1906–1974). Chicago World’s Fair, A Century of Progress poster, 1933. Screenprint, 421/8 × 283/8 in. (107 × 72 cm). Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. Right: Published by Frank E. Cooper, NewYork Printed by C. T. Art-Colortone, Chicago “Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp)” by Augusta Savage, New York World’s Fair postcard, 1939. Offset lithograph 51/2 × 39/16 in. (14 × 9 cm). Art and Artifacts Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Augusta Savage’s Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp), a large sculptural ode to the “Black National Anthem” by her friend James Weldon Johnson and his brother John Rosamond Johnson, was ultimately one of the most popular attractions at the New York World’s Fair. The sixteen-foot sculpture, which resided in the court of the Contemporary Arts Building, was unfortunately destroyed when the fair closed in 1940 and survives today in the form of small-scale replicas resembling the maquette Savage presented to Grover Whalen, the president of the New York World’s Fair Corporation. The fairs distilled a complex, often contradictory set of values that political and corporate figures in power strove to project to the public and that permeated American visual culture over the course of the decade: that consumerism and moderation, tradition and innovation, and imperialism and cultural tolerance merged to form the core of American identity.

Marquee: Harry Gottlieb (American, born Romania, 1895–1992). Rock Drillers, 1939. Screenprint, 171/2 × 151/4 in. (44.5 × 38.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of New York City W.P.A., 1943 (43.33.946)