Chassica Kirchhoff is a treasure hunter of sorts.

As assistant curator of European sculpture and decorative arts for the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), she is tasked with researching, identifying and acquiring artwork for the museum’s collection.

And wait until visitors see what she’s dug up.

“This is a once-in-a-curator’s career acquisition,” Kirchhoff said of a rare 16th-century automaton clock that she tracked down. “I had been on the hunt for an automaton even before I came here.”

Automaton is the Greek word for an object that moves on its own.

This technology was used in clock production during the 13th century, evident by the clock towers that appear in public places across Europe, but the clock acquired by the DIA is among the first made for domestic use.

And it still works.

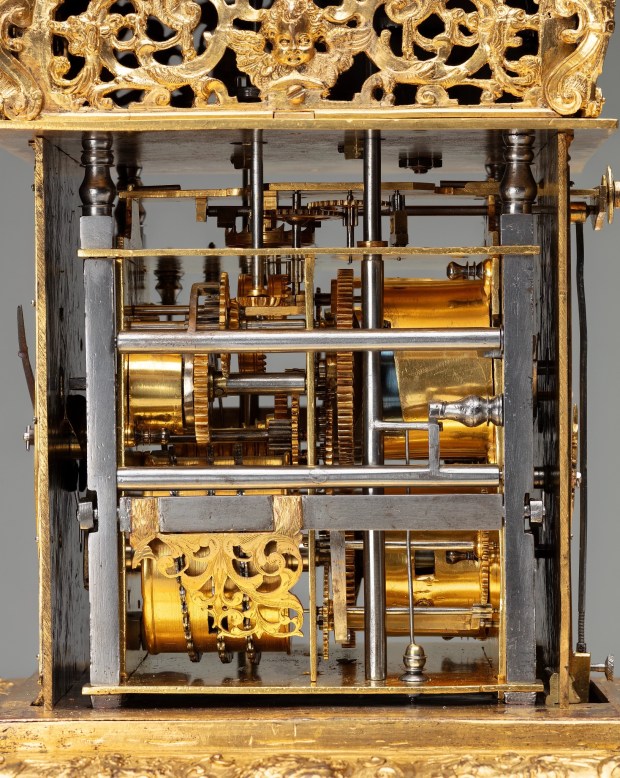

That’s part of the beauty of this mechanical wonder known as “The Rooster’s Crow.”

How it came to be part of the DIA’s collection is also a wonderful story. After all, curators don’t just shop for artwork, especially when a piece can cost anywhere from $200,000 to $200 million.

Kirchhoff declined to share its price, but historians would say it’s priceless due to its age and design. As Kirchhoff learned through her research, once the technology for moving mechanisms was available to metalsmiths creating clocks for public spaces, it was only a matter of time before artists working with gold, silver, steel and other metals would expand upon its use.

“It was a very explosive era,” Kirchhoff said of the 16th century. “You can see that by all of the pieces that were made at the time.”

This particular clock features a gilt copper and brass case with engraved silver panels crowned by a rooster automaton that flaps its wings and opens its golden beak as if to crow each quarter hour. When Kirchhoff learned that it would be among the pieces displayed at a European fine arts fair, she flew to the Netherlands for an early viewing, a privilege that’s extended to museum curators.

As soon as she saw it, she knew it was a remarkable piece. What confirmed her find was the excitement that it created, among curators from around the world, when the clock’s owner demonstrated how it worked.

“He wound it and it drew this huge crowd of people,” said Kirchhoff, who then told the owner to put it on reserve for the DIA.

“We planted our flag early,” she said.

What followed Kirchhoff’s discovery was an extensive acquisition process that took over a year and included her identifying the piece in question, negotiating a purchase price and having it shipped overseas from the Netherlands to Detroit.

How it arrived, we’ll never know.

The who, what, when, where, and how a work of art is shipped to their destinations is a secret that curators never reveal, but makes for great fodder in Hollywood movies. Even when the artwork arrives at its destination, access to the piece is only given to a few people. Security, however, did not stop people from hearing the sounds of the rooster’s crow within the museum.

“Everyone fell in love with it,” Kirchhoff said.

Arriving along with the piece, but traveling separately, was the former owner and clocksmith who restored it to its original beauty and provided Kirchhoff and a few other museum staffers with the training needed to properly wind, set and maintain the piece.

“You don’t just wind a 440-year-old clock,” Kirchhoff said while watching a video created by the DIA showing the meticulous steps required to wind this ancient but modern piece that stands 24 inches tall.

While its exact origins are still unknown, parallels in clockmaking techniques and metalworking styles suggest it was made in the German cities of Augsburg or Nuremberg. Kirchhoff also has been doing a lot of object-based research that involves studying and researching details in the clock’s design and this has led to further clues about the clockmaker, artists and metalsmiths involved in its design.

The eagle on the back of the throne at the top of the clock, for example, is identical to the eagle on three other clocks made at the time. When the clock strikes the hour, seven very detailed figures, promenade around an enthroned emperor under a canopy that resembles a crown. Kirchhoff has learned these figureheads represent the four princes and three archbishops who elected each ruler of the Holy Roman Empire. There are two engraved inscriptions that allude to its iconography: Hane Crei (Rooster’s Crow) and Coevorsten (prince-electors). Silver panels on the clock’s sides are engraved with landscapes and a church that might help identify the artist. The mechanics on a clock are frequently signed, but this one is not, which could mean it was a collaboration of several local artists.

In the end, Kirchhoff hopes to publish the full story on the Rooster’s Crow, which will enhance the experience of visitors even further including thousands of students from Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties.

“This is really an important object for teaching,” said Kirchhoff, who taught art history at the University of Kansas.

Roosters have long been associated with alarm clocks. So, it’s not unusual that this timepiece crafted in Germany during the Renaissance has one on top. Not many, however, flap their wings and chime like this one. What also makes the clock a remarkable teaching tool is that its sophisticated design serves as an example of the advanced technology, engineering and metalworking artists were using at the time. It’s a story of invention and creation similar to those shared by Michigan’s industrial artists and manufacturers.

“It makes me really happy that I’ve been able to make this accessible and visible to thousands of people,” Kirchhoff said. “It’s really the best-case scenario for us.”

Students who recently had a chance to see the clock had high praise.

“It’s amazing because it’s from the old days and it’s very detailed. You can see a lot of things,” said Jean Beauregard, who was among the students from Rodgers Elementary School in St. Clair Shores touring the museum’s Northern Renaissance gallery.

“I really like it because it’s not like a digital watch,” added Avary Bradford, who also enjoyed the video showing how the clock works.

“I’ve seen the bird with wings somewhere before, maybe on another clock,” said Daniel McAlpine, who was chaperoning the group of fifth graders. “But this one is amazing.”

Once-a-month winding is necessary for maintenance of the clock. This has been incorporated into a monthly program that brings movement and sound into the gallery and offers visitors an immersive experience of early modern craftsmanship and innovation.

The next winding of the clock will be Feb. 7. The gallery will be closed to the public while the automaton is wound. Visitors will be able to view the clock afterward and hear it chime every hour for the rest of the day.

“We are excited to acquire this rare clock for our permanent collection, as it represents the height of 16th-century artistic skill and technological innovation,” DIA Director Salvador Salort-Pons said. “We are pleased to offer our visitors an opportunity to see it up close and in action during our monthly demonstrations.”

FYI

The Detroit Institute of Arts is at 5200 Woodward Ave., Detroit. General admission is always free for Macomb, Oakland and Wayne County residents.

Hours of operation: 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays through Thursdays, 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. Fridays and 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays.

For more information, visit dia.org.