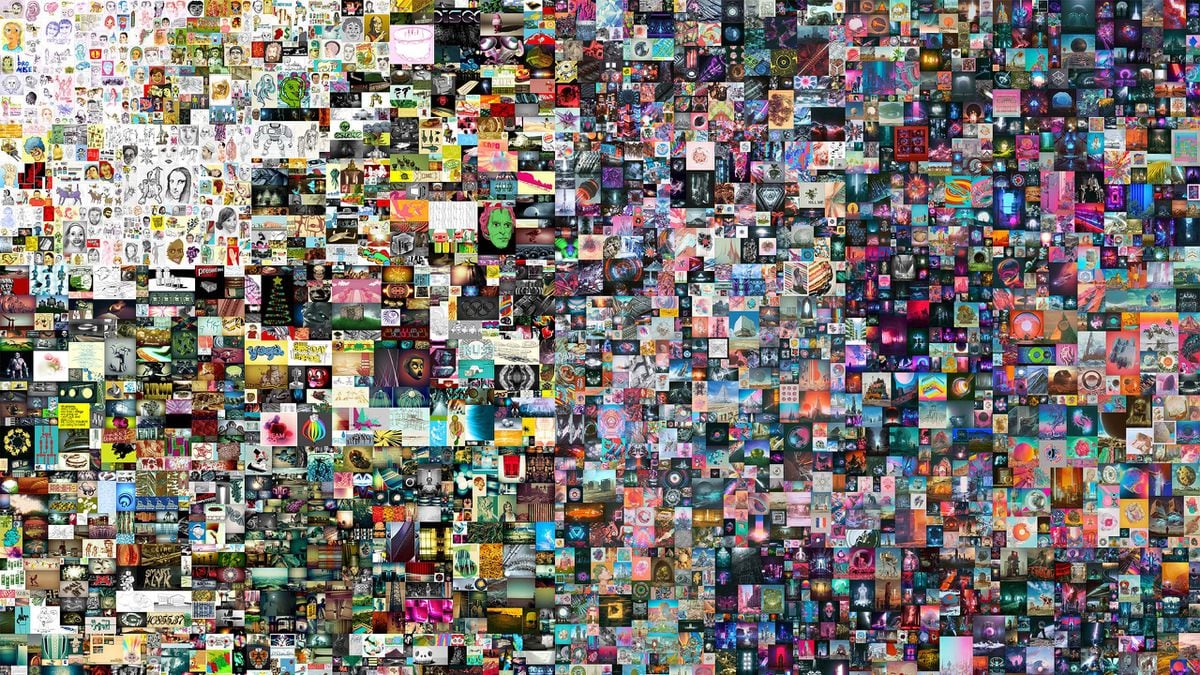

Just two years ago, when most art historians still doubted the authenticity of the Salvator Mundi (a work attributed to Leonardo, which went for $450 million at auction) and were stunned by the resale of street artist Banksy’s self-destroying painting Girl with a Balloon (which fetched $22,920,450), there was another significant shock at Christie’s New York headquarters. A digital NFT (non-fungible token) entitled Everydays: The First 5,000 Days by American designer Beeple sold for $69.3 million to a mysterious buyer, alias Metakovan (who was later revealed to be Indian billionaire Vignesh Sundaresan). The prized work was actually a digital collage composed of images that its creator had been sharing on the internet since 2007; thus, the Sandokan of the moment had just paid a millionaire for the (unsurpassed) oxymoron of an “original copy.”

NFTs seemed to be a successful penultimate auction format that could keep the flame of the globalization of money alive, but in reality they were nothing more than a vulgar copy from which infinite reproductions could be extracted. The only thing unique about them was the certification, an authenticated fiction that the buyer was in possession of the original, so to speak. The NFT was a ghost’s sheet without the dead. As cyberfeminist artist Cornelia Sollfrank put it in My First NFT and Why It Wasn’t a Life-Changing Experience: “I am fascinated by digital artworks because of the inherent impossibility of identifying the original.”

David Hockney — whose work had fetched a record $87,316,800 in 2018 for Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972) — did not hesitate to slam the still-nascent format, either (Kevin McCoy’s Quantum (2014) was the first tokenized artwork). Interviewed on the well-known podcast Waldy and Bendy’ s Adventures in Art, Hockney acknowledged not understanding how NFTs work, “those ridiculous little things are the tools of thieves and international swindlers,” the 84-year-old English painter blurted out. The show’s hosts, art historians Waldemar Januszczak and Bendor Grovesnor, didn’t bother to explain much more about these cyber-goods, but they did say that they had an eternal life, at least on the internet. That was the theory.

The NFT is a digital identifier inscribed on a blockchain, an unmodifiable ledger that’s already in use in virtually every field of the entertainment industry. It certifies the ownership and authenticity of an asset that is on a website, under centralized control, but could be modifiable as images are not stored on blockchains. There is no direct link between the certificate and the digital information it authenticates. This business model’s usefulness resides in the exchange and sale of digital goods as if they were material goods, and its immediate success in the artistic environment does not stem from the enjoyment of a work but rather from investment interests. Why would a collector want to have the certificate of something that might disappear from the internet one day? The most likely answer is that the NFT holder is not an art collector but a crypto-investor.

Now that we are catching a glimpse of NFT art’s imminent decline, doubting the definitive value of the NFT is not a function of the reticence that has always existed toward some artists or the currents they represent. The shock of the new has always been conflated with modernity. Fauvism, one of the best-prepared artistic revolutions of the 20th century, lasted for only one season, but what a season! The slogan that a critic gave those savages of color at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, Donatello chez les fauves (Donatello among the Wild Beasts) is one of the most celebrated baptismal moments. As for collage, its impact has carried through to the present day (Beeple’s NFT is a collage). Invented by Braque and Picasso in 1912, it changed the vocabulary of Cubism, breaking with an entire system of pictorial representation based on the gold standard of “likeness.”

As historian David Joselit argues, “Duchamp used the category of art to liberate materiality from commodifiable form; the NFT deploys the category of art to extract private property from freely available information.” In short, it’s producing verifiable digital scarcity, with the consequent — very high — energy expenditure, the opposite of the zero-environmental impact of flipping over a urinal.

Duchamp was the first artist to openly become the buyer and seller of his own work. In 1919 (after he had already given the Mona Lisa a goatee and mustache), he paid his dentist with a drawing of a handwritten check for $115. Later, he recovered his Chéque Tzanck, named after the toothpuller, for 1,000 francs. If the signature confers value on the work, what prevented him from drawing his own checks and recovering them at a profit? He did not do it for speculative purposes, but rather because he wanted to introduce the reproduction of the check in the replicas he made of his La Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Suitcase). Seen through the prism of history, Duchamp seems like a classic revolutionary to us, a Donatello among the NFTs.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition