Non-medical academic research on wine has two main strands. The first, founded on statistics, fails consistently to prove a link between taste and perceptions of quality. The second, founded on economics, parks the idea that wine’s for drinking and considers how much it costs.

Their common thread is subjectivity. The story that attaches itself to every bottle will determine what people taste as much as how they perceive value. And because wine is an experience good — the only way to find out whether you like it is to consume it — the crux of the story is usually price. A bottle that sells for £100 is better by £90 than a £10 bottle, at least until the cork is pulled, and even afterwards hardly anyone has the critical abilities needed to change their preconceptions. Subjectivity is what makes wine a perfect Veblen good. It’s made of grapes and biases.

That makes wine an odd asset class, though not in all ways.

“There is a considerable overlap between corporate bonds and wine,” write Robbe Van Tillo and Gertjan Verdickt, of Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, in a recent paper. “They both have ratings, maturity (drinking window), suffer from default risk, trade on financial markets (auction houses), and exhibit a fixed supply once issued (produced). Also, the level of liquidity could be a severe concern for investors.”

By “default risk” they mean the wine might be undrinkable and presumably the liquidity reference is Belgian academic humour. They also talk about an “emotional dividend” in place of the coupon and don’t really crack the maturity thing (a spoiled wine still can be drunk, and its drinking window is an estimate rather than a cut-off point) so, overall, it’s not a perfect analogy. But it holds well enough to see if wine trading magnifies biases that might exist in other markets.

The bias that interests the authors is selection neglect. It’s a term adopted by behavioural economics to describe the tendency for people to see something as representative even when they should know it’s not. When fund managers advertise themselves using their best-performing funds, or when the price gain of a few crypto tokens gets whipped into a bubble, that’s the exploitation of selection neglect.

Van Tillo and Verdickt investigate how the bias affects wine auctions. Their hypothesis is that bidders routinely overpay because they choose to ignore negative information. Tl;dr, they do, and by a lot.

Auction houses are breeding grounds for selection neglect because not all lots reach the reserve price. Anyone who makes decisions based only on completed sales will be ignoring the generally lower valuations being attached to the unsold goods, and will probably be too optimistic as a result. Wine auctions are particularly prone to the bias because a specific vintage only sells at auction occasionally, so investors don’t get price updates frequently enough to rebase their expectations.

This is a big study, examining 3.3mn sales over nearly 20 years across 41 auction houses. Bottles cheaper than $20 and more expensive than $50,000 are excluded, and the rest are benchmarked by quality, maturity and unusualness using Wine Advocate scores.

A data set this big throws off all sorts of findings that, while not directly relevant to the conclusion, help fill out the scene. One sidebar finding is that (wine) rating agencies are rubbish.

The Robert Parker effect has been studied a lot by academics, with a high score from his Wine Advocate site shown to translate to a (modestly) higher retail price. Unsurprisingly, all the wines that go to auction are Parker-approved, albeit on an unhelpfully narrow range.

Van Tillo and Verdickt find that the average bottle has a hammer price of $608.51 and a Wine Advocate score of 93.93, which is towards the upper end of what Parker considers “outstanding”. But sales go as low as $28.51 and the study’s lowest band for quality starts at 85, which is just one notch down from “outstanding” on the Wine Advocate scale.

More interestingly, the correlation between hammer price and Wine Advocate score looks weak to negligible (r=0.222). And the average future returns from wines with higher scores are lower. For as much as it clearly makes some people happy, collecting 100-pointer bottles like Pokémon is a lousy investment strategy.

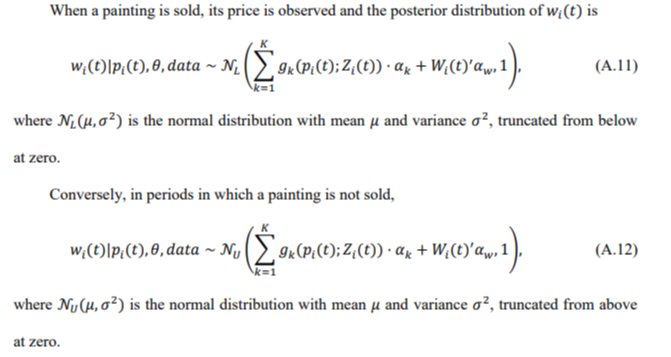

So if expert opinion doesn’t matter, what does? To find out, the study uses unsold lots to put a theoretical fair value on each bottle, known as the latent price. Scholars of Bayesian inference will know already about latent pricing as it applies to auctions and it’s a steep learning curve for the rest of us, but if you’re curious, here’s how it’s summarised in a 2016 paper on returns from art investment:

The first, not wholly surprising finding from all that working is that liquidity matters to price discovery.

Where there are a lot of completed sales, achieved prices at auction stay fairly close to latent prices. But because with wine there are few repeat sales, blind optimism takes hold and the fair-value gap gets very wide indeed.

Reducing the sample to wines that traded at least twice in 12 months cuts the average hammer price to $541.12 per bottle. The hypothetical fair value on these bottles (the latent price) averages just $247.68. That’s a more than 100 per cent premium and it seems to be caused by bidders’ selective amnesia when it comes to unsold lots:

Traditional factors cannot explain this finding. The qualitative conclusions hold even if we control for wine-level characteristics, such as price, ratings, time to expiration, illiquidity, lottery demand, and salient features. The results are also robust to smaller changes in the regression design, such as the location of production and sale, holding period, and wine styles.

Cheaper wines are more likely to sell at too high a price. These are “more demand elastic, more exposed to non-proportional thinking, or more likely bought by non-institutional owners,” say the authors. (Non-proportional thinking is when investors get overexcited about absolutes rather than percentages. There’s some evidence, for example, that stocks become more volatile when their per-unit value is cheaper.)

They find that bidders are more likely to ignore negatives in countries where there’s a get-rich-quick culture, such as the US. Having a big domestic wine scene also seems to encourage selection neglect, as does wealth inequality. In both cases the problem may be information: wine countries generate too much useless data, while those with a wide rich-poor gap have too few participants to provide regular and reliable price fixes.

The study’s main limitation is that all bottles in a vintage are considered identical even though some might have a deeper ullage, a tattier label or a notable previous owner. Other distortions, like home advantage and dodgy auctioneers, should be smoothed out by the epic size of the data set.

Though not the point of the research, it’s positive on wine as an asset class. The average after-costs return across the sample is 1.8 per cent per month, or 23.9 per cent a year. The range is very wide though (-22.5 per cent to 46.6 per cent) and the median return is negative at -1.4 per cent a month.

Straightforward passive approaches to wine investment won’t work. It’s a bottle-pickers’ market, and the ones to pick are the ones most susceptible to selection neglect. It’s shown to be a better predictor of price appreciation than price differentials, momentum and salience.

Buying just the top quintile of mispriced wines rather than the bottom quintile improves returns by 5.7 per cent a month. The investment advice here really is to ignore rating agencies, buy anything that’s low-priced and doesn’t trade much, then look to sell it wherever oenophilic hicks and greedy yokels gather.

Does the finding have a wider application? There are very few conventional asset classes where value is as altogether subjective as wine.

The parallel the authors invite is with junk bonds, since in both cases skilled active management can exploit mispricings born of illiquidity. That opportunity looks gone though. The risk premium on high-yield bonds narrowed after bond ETFs arrived to loosen things up. Buyers’ selective biases and over-optimism have probably been arbitraged away by now.

But reduced yields from junk have probably contributed to the boom in private credit, which doesn’t trade by definition so has a guaranteed illiquidity risk premium. And returns from direct lending can look amazing, depending on how much information an investor chooses to ignore.

As a breeding ground for cultivating selection neglect, private credit investment has a lot in common with wine auctions, and if it all goes wrong the holders won’t even be able to get drunk.

Further reading

— Jancis Robinson (FT)