In 2020, the Brooklyn-based art collective MSCHF bought a Damien Hirst print for $30,000 and cut out each of its 88 spots, selling them for $480 apiece. It then auctioned off the leftover paper, retitled “88 Holes,” for more than $260,000.

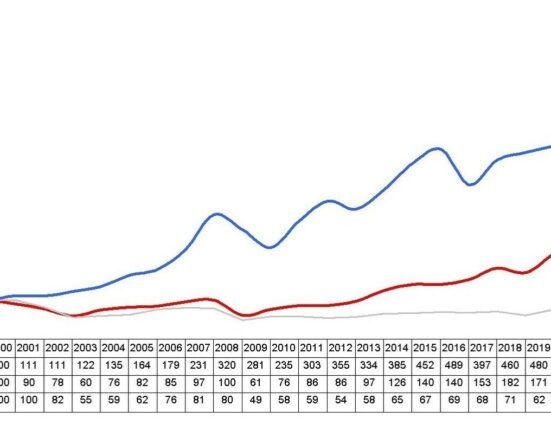

While cutting up and selling pieces of works of art remains the stuff of highbrow pranks, increasingly, investors are buying fractions of works of art. The motivation is easy to understand: Contemporary art investments have outperformed the S&P 500 over the last 25 years (offering a 14 percent annual return versus the S&P 500’s 9.5 percent annual return), according to Citi’s Global Art Market report.

One of the leaders in the fractional art space is Masterworks, based in New York City and founded in 2017. The company says it has more than $300 million in art assets under management.

Here’s how it works: Masterworks signs up members based on their investor profile (it currently claims more than 250,000 registered users, although probably far fewer have actually invested). Those members get access to new deals every few days. The company creates a Delaware-based limited liability corporation, registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), to “facilitate an investment” in a single work of art by a given artist (one recent example was the renowned German visual artist Gerhard Richter, for which the fund allowed a maximum of $9 million). That company is then chopped up into hundreds of thousands of shares, which are sold to Masterworks’ members until they are gone.

At a fixed point after the shares have been bought, the work of art is professionally appraised, and its investors are given quarterly reports about the work’s value. Eventually, the work is sold, and investors are paid their pro-rated share of the difference in value, minus Masterworks’ fees. The SEC filings indicate that a minimum of $15,000 is required to invest, and a maximum of $100,000 is allowed, although a Masterworks representative told Worth that both of these limits can be waived if individual circumstances warrant (a first-time investor might be allowed to put in $10,000, for example).

Other investment firms take a different approach. At Yieldstreet, they invest not in a single painting, but in a collection of paintings in a genre to diversify the fund. One of Yieldstreet’s funds, for example, collects the work of Harlem Renaissance painters, including Alice Neel and Jacob Lawrence. Yieldstreet’s managing director and head of art investments Rebecca Fine told Worth: “We target artists who are sort of underappreciated and undervalued, where we really consider that there is room for great appreciation in value.” Interestingly, the vast majority of art that gets securitized and sold is modern/contemporary art. Investment firms say their algorithms show that these works appreciate the most and come up for sale most often.

Fractional art purchases may not suit the needs of all investors. At Yieldstreet, art investors commit to a five-year fund, with two possible one-year extensions. So, while the return can be impressive, it requires much more patience than a stock or ETF. At Masterworks, the investment tie-up in an individual work can be even longer—three to 10 years, although the company points out that it has an incentive to sell sooner rather than later. Masterworks does provide a kind of emergency liquidity exit; its art investors are allowed to sell their shares on a secondary market, but there is no guarantee that the secondary market will be able to make the investor whole.

Moreover, despite the sometimes staggering increases in value that can take place for individual artistic works, prices can go down as well as up. The COVID pandemic had a profound effect on art sales; the lack of in-person art fairs meant far fewer sales, creating in 2020 what an influential art industry report dubbed “the biggest recession in the global art market since the financial crisis of 2009.”

Even so, the market has recovered since, and the long-term numbers are encouraging. And for lovers of art who are also interested in earning investment returns to beat inflation but could never afford to spend millions on a work, it’s hard to improve on owning a piece of an artist you admire.