By Kai Curry

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

I’m in love. I’ve walked into the Kelly Akashi: Formations exhibition at the Frye Art Museum on First Hill and it is at once familiar and new. It’s the largest showing of Akashi’s work thus far, covering up to 10 years of her exploration and experimentation in various media.

There are three rooms in the exhibition, as well as outlying pieces at the entrances. After listening to a short introduction at the Frye Summer Exhibitions Opening Reception on June 16, with Akashi herself present, I went into Formations backwards from the direction of the auditorium, so for me, it was Life Forms-Being As A Thing-Inheritance. I think this is a better way to go because you get a feel for Akashi’s work and self, if you will, before you walk into Inheritance, which deals with her Japanese American family’s incarceration camp history.

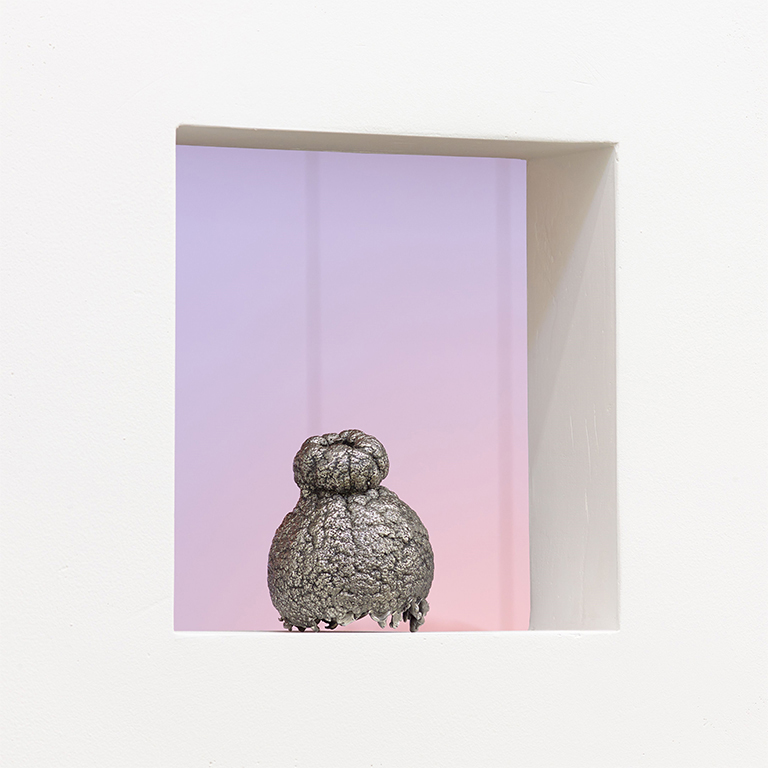

I can’t imagine going the other way, and having no context, which maybe is why when I entered the Inheritance gallery, there was an old man in front of me laughing and unable to resist touching the foremost pedestal and the items displayed on it. His friends giggled and reminded him not to touch, but he reached out over and over anyway at the earthen slab, rough, littered with a few solitary objects. A hand. A glass tripod and flower. A Japanese style hair bun. A branch.

Kelly Akashi. Be Me (Japanese California Citrus), 2016. Lost-wax cast and polished stainless steel. Courtesy of the artist, François Ghebaly Gallery, and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

Having listened to the talk between Akashi and the Frye Chief Curator and Director of Exhibitions, Amanda Donnan, on June 18, I knew that these objects reference the incarceration camp at Poston, Arizona, where Akashi’s father was held. Particularly, they reflect Akashi’s own experience and that of other descendants who have visited these camps prospecting, you might say, for remnants of their parents’ and grandparents’ time there. It was here that Akashi took back up her interest in analog photography—which is where she started as an artist—and also further developed her scientific fascination with geology and with art forms such as bronze casting.

I don’t see anything to laugh about. The room and everything in it speaks immediately of pain, loss, separation, of the past lives and the broken lives of those that were imprisoned there. It is pieces left behind and picked up by those who visit the camps now. Akashi has placed upon the earthen-work pedestals (which she makes herself) items that hearken back to her own artistic tradition, as well as to those who came before. She doesn’t have much to go on, she told the audience on June 17, because her father has now passed away. Like many, she is excavating.

Donnan mentioned that Akashi has previously said she is “interested in this idea of objects talking back, or emoting, in a way,” to which Akashi answered, “Can objects or sculptures be carriers of emotion and transmit emotion? Can I somehow get them to…communicate feeling?” This was the “problem” Akashi wanted to tackle and she has done so successfully. Akashi wants her work to resonate with the viewer. She has even included a bell atop one display, hanging from a rope that is a common motif—the connection of the umbilical cord, of humans to other life forms, of us to our ancestors and to each other, pulling, tying, hanging.

“I wanted people to be thinking super deeply and abstractly inside themselves [and thought] it would be great if there was a part of the work that would reach inside of you and touch you in a deep part of your body.”

Akashi is not an all-somber individual.

“I’m going to keep this short so it’s not too long,” were her introductory remarks at the reception, and everyone laughed. She came to her talk with Donnan dressed respectfully yet casually, in pink socks and stylish tennis shoes, her hair cropped short versus how it looks in her portfolio photos—or how it looks in the “effigy” of herself she made in stone that sits outside Life Forms. Akashi is a highly scientific artist or artistic scientist. Her initial interest in analog photography progressed to candle making (where she learned a lot from her mother) to glass making and sculptures in multiple media, not to mention a bevy of other types of photography, including utilizing medical imagery, such as CT scans, to create her art.

Right now, she is working on a new piece that she will reveal at the next phase of this moving exhibition, which will be at the Henry Art Gallery on the University of Washington (UW) campus, from Sept. 30 to May 5, 2024. This piece will be based partly upon an archive of astronomical glass plates that Akashi has been viewing at UW— “moving on from a geologic time scale to a galactic time scale,” described Donnan.

“What’s exciting to me about these objects, or bodies in space, is that they have weird relationships, just like us,” said Akashi. She has been “looking at how different bodies interact and relate to each other…there’s just some really foundational things going on with bodies and gravity in general. I’m excited about it.”

Akashi mentioned she would likely talk around her work and herself, and I might be talking around it now. She is an intelligent, diligent, and devoted woman whose work is also multi-layered and which draws from those layers of connection. Take for instance her fascination with the insides of seashells (not the outsides) and how they resemble our own insides, our organs. She is interested in our link to other people when she places her grandmother’s ring upon a glass casting of her own hand—which she has recast dozens of times, each time destroying the original, and in the process connecting to her own self and its journey through space and time.

I can’t be sure but I’m almost sure I also heard a dismissive remark—dismissive of contemporary art, of art one doesn’t understand, maybe of Asian art—from that trio of giggling senior citizens in the Inheritance gallery. I was pleased in general with the diverse crowd that came to the Frye, but I don’t know what business someone had being there that could not appreciate—and did not want to appreciate—Akashi’s work or the work of others currently on display at the Frye.

My heart fell in love and was broken. There was a reason for a smile, at something you recognize or understand; at something that delights by its innovation, its creativity, its precision and painstaking effort, and the way it makes you think and feel. But there was no reason for laughter.

Kelly Akashi: Formations is organized by the San José Museum of Art and curated by Lauren Schell Dickens, Chief Curator. The presentation at the Frye Art Museum is organized by Amanda Donnan, Chief Curator and Director of Exhibitions and runs until Sept. 3, 2023.

Kai can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.