VIA Metropolitan Transit is still years away from opening service on its first Advanced Rapid Transit (ART) lines, but developers and transit advocates are already envisioning big changes for the surrounding corridors.

Transit experts say having a thoughtful development concept, complete with preapproved zoning codes, is critical to making an investment like the VIA’s ART lines successful. To encourage a less car-centric community, they say, transit needs to be surrounded by dense, walkable communities that provide housing and amenities to a large population of potential mass transit riders.

“It’s hard to get the whole thing started to convert a place back to a walkable community, but you really have to have that as the goal, and you have to have a vision,” said Andy Kunz, president and CEO of the Transit Oriented Development Institute in Washington, D.C., which studies and promotes best practices for development around transit.

“All the building and the zoning codes have to match the vision,” Kunz said. “And yet, typically, every one of the codes on the books says the opposite” of what’s needed for a transit corridor.

City leaders are gearing up for an arduous process of figuring out what that vision should be and what changes are needed to make it possible.

VIA sought to get ahead of some of those issues before the pandemic, but growing interest in the corridors is now likely to yield a vibrant public input process for a city that’s deeply divided on how to approach development.

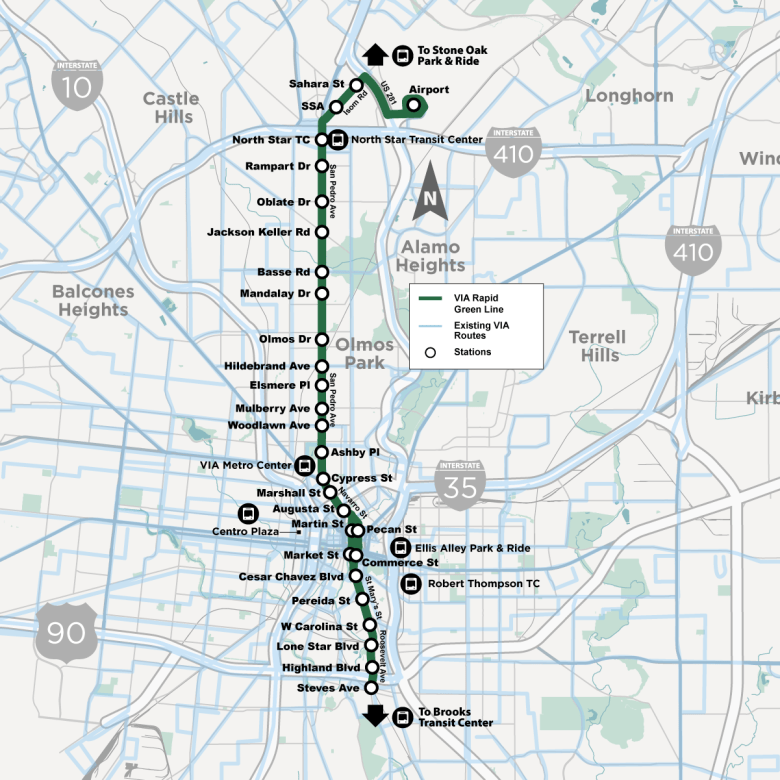

A Council Consideration Request (CCR) filed last month by Council members Marc Whyte (D10), Sukh Kaur (D1) and Teri Castillo (D5) asks the city to create a transit-oriented development (TOD) plan for VIA’s two ART lines, which are slated to run north-south, from San Antonio International Airport to the area around the Spanish Colonial missions, and east-west, from the West Side along Commerce and Houston streets to Frost Bank Center on the East Side.

“A lot of people fear that this whole VIA deal will be a big waste of money,” Whyte told the San Antonio Report. “We need to figure out how we’re going to develop around it so people are using it.”

The CCR calls for a plan that incentivizes redevelopment along the lines to support transit ridership, facilitates a walkable community without excluding motorists, encourages housing choices for people of various income levels and minimizes barriers to retail development.

Multiple city departments — from Development Services to Transportation to Neighborhood and Housing Services — are expected to solicit feedback from the council’s Governance Committee at a meeting in the coming weeks before starting the process of gathering community and stakeholder input.

Mayor Ron Nirenberg already has assembled a technical working group within the city’s Housing Commission, so that the recommended TOD goals can be translated into zoning code that aligns with the city’s greater housing goals.

“A good TOD plan would incorporate and align all of the initiatives that the city has going: housing affordability policies, economic development policies, health policies, equity policies, land use policies,” said interim Transportation Department Director Catherine Hernandez, who is overseeing the CCR.

“We need to make sure that we set up the right toolbox so that what we’re doing with transit aligns with what we want to do with all of these policies.”

Early steps toward walkability

Transit-oriented development typically refers to development around a rail project, said Kunz, drawing major investments that don’t normally follow bus systems.

“Rail systems are essential to making TOD take off,” he said. “You’re not going to get whole multiple communities developed along a bus line.”

But after decades of attempts to construct light rail and a street car system in San Antonio failed, a rapid bus line running north-south, known as the Green Line, and one running east-west, known as the Silver Line, will be the closest San Antonio has ever come to mass transit.

VIA’s 12-mile, north-south route will connect the San Antonio International Airport to downtown and continue on to the Spanish Colonial missions. It’s expected to be operational by August 2027.

The city is still looking for a local funding match for the Silver Line, which could start at North Gen. McMullen Drive on the West Side and run along West Commerce Street and East Houston Street to the Frost Bank Center on the East Side.

Both projects rely heavily on funding from the Federal Transit Administration, which funds transit projects across the country and currently shares many of San Antonio’s goals when it comes to making housing affordable, improving air quality and connecting residents to jobs, schools, health care and other transit.

Before the Green Line, San Antonio had not received a Department of Transportation grant in over a decade.

“Putting these ART corridors in the city really put us on the map federally because this is federally funded, first-of-its-kind here,” Hernandez said. “Getting us on the map is very important for San Antonio because we don’t want to be behind the curve.”

To help the ART lines bring about the kind of transformative change the city and federal government anticipate, the FTA already awarded the city roughly $1.5 million in grants to develop accompanying TOD plans.

Code Studio, a national zoning consultant with an office in Austin, was selected for a 2018 grant to make TOD recommendations for the Green Line, which VIA had hoped to include in the city’s Unified Development Code (UDC) amendment process for the 2020 fiscal year.

The work was delayed due to the pandemic, however, and VIA now projects the final product will be completed in 2024.

“We looked at the city’s UDC and said these are the kinds of things that might benefit TOD,” VIA President and CEO Jeff Arndt said of the Code Studio plan at a recent development forum hosted by the North San Antonio Chamber of Commerce. “The good news is I believe that what we have right now takes you to 85% of where you want to be.”

New seats at the table

But with City Council eyeing action, many more stakeholders are likely to be involved in development plans for the ART corridors.

“When other cities have done things like this, one of the biggest mistakes is when they don’t get all the stakeholder input before they get going,” Whyte said. “We need to involve all the stakeholders and developers, [and] get the zoning in place, to make sure what gets developed along this line is appropriate.”

Affordable housing advocates have already gotten involved in one of the city’s first attempts at TOD, demanding that more of the units at the Scobey Storage Complex be offered below market rate. The complex is near VIA Metropolitan Transit’s Centro Plaza, which aligns with the proposed east-west ART line.

Developers in San Antonio also are eager to get involved with ART corridors and want flexibility in what they can build.

The Real Estate Council of San Antonio, for example, wants to make sure development incentives are available for market-rate housing along the corridor, as well as affordable housing. Common incentives along transit corridors include reductions in the minimum parking requirement, density bonuses and setback and landscape buffer reductions, which can be used to favor one type of housing over another.

“If you have one corridor that’s all affordable housing, then the market determines that you’re going to have only these types of restaurants or these types of stores,” said the council’s CEO, Stephanie Reyes. “It doesn’t create a mixed development.”

TOD experts say mixed-income communities, as well as buy-in from developers, are critical so that the transit lines expand beyond traditional bus ridership.

Developer Ed Cross said he has already met with VIA’s leadership about the proposed TOD and what it could mean for the ART corridors in terms of improving density and encouraging new development.

“The TOD zoning which I attained for Vicinia is just a remarkable zoning ordinance that, just in and of itself, is a great incentive for development along these corridors,” he said, adding, “I think the more things you can do to help incentivize development in a challenging time, the better.”

Neighborhood leaders along the Green Line also want a say in what the corridor becomes. Several of them met with VIA over the summer and expressed concern about the agency leading the TOD efforts without appropriate public input.

“You have a runaway agency on your hands with a lot of money,” said Greater Harmony Hills Neighborhood Association President Patty Gibbons. “They are not neighborhood responsive.”

While the changes are destined to come with the density that some current residents oppose, the city’s Housing Commission is focused on how to help existing residents share in the development.

Jim Bailey, an architect who oversees both the commission’s TOD working group and its committee on removing barriers to affordable housing, said the city can use TOD to help keep housing affordable in those neighborhoods and to make sure homeowners have the ability to capture value increases.

“There’s a whole series of those tools,” Bailey said.

Progress for whom?

Major changes to the ART corridors aren’t likely to come quickly, in part because of development that already exists along both lines.

“You have to home in on a few sites and change building codes, change the zoning codes, shrink the streets, reduce the parking, make the sidewalks wider, put benches in, add street trees and nice lamps, then give developers incentives to come in and fill in any remaining gaps,” Kunz said.

Often, that starts with a historic district, where bones of a walkable community already exist.

Along the Silver Line, the proposed commercial and residential development around Centro Plaza is a prime example. The area offers rich history and design continuity, but the mostly vacant property is well-positioned for redevelopment.

Along the Green Line, Bailey pointed to a stretch of San Pedro Avenue between Basse Road and North Star Mall as a potential opportunity.

“In some places you’ve got almost a quarter-mile of asphalt and underutilized parking lots and underperforming retail,” he said.

But development along the majority of both lines will have to account for communities and businesses that already exist.

Some of the most vulnerable communities are the reason the ART lines were first proposed, to offer an affordable means of transportation to people whose jobs require them to be on-site.

“These are real locations, they’re streets that are already in place, they’re real neighborhoods and real people that live along here,” Bailey said. “Whatever happens is going to have to be done through a long, careful community conversation, ensuring that stakeholders are not just informed what’s going on but have the ability to engage with the process.”

Business and development reporter Shari Biediger contributed to this report.