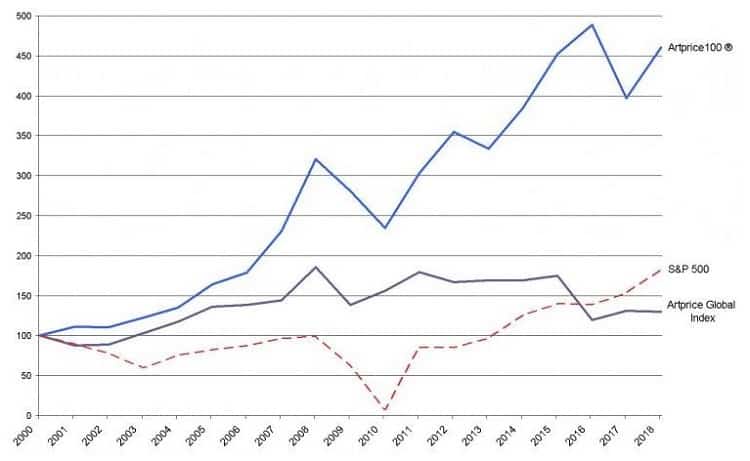

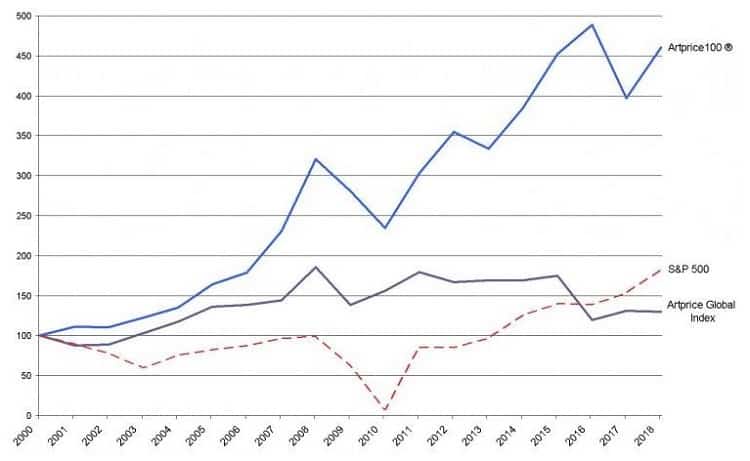

Fine art investing has typically been the forte of people who turn left when they get on a plane while the rest of us turn right. And for good reason. Investing in art isn’t just about showing your friends how sophisticated you are, it’s also a fine place to park some cash. Any number of studies out there show that art as an asset class has outperformed stocks. For example, a Swiss company called Artprice makes a business out of giving people access to art pricing information which they obtain from more than 6,300 auction houses. The Artprice100 Index tracks the 100 most popular artists and shows how they trounced the S&P 500 for the past 18 years.

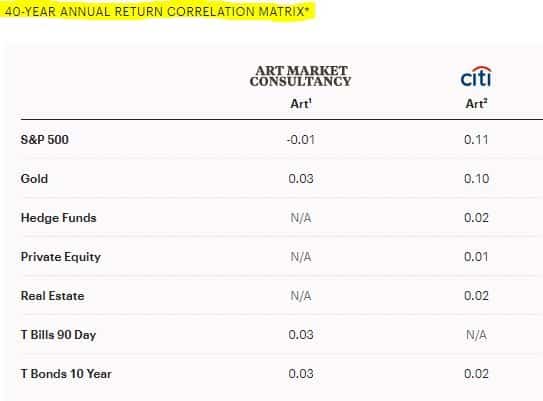

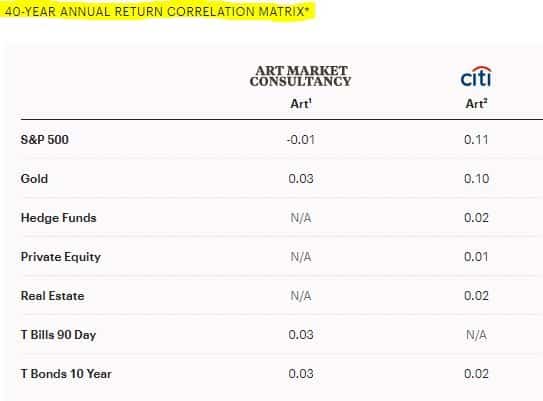

Of course, you can always torture the data until it tells the world that your investment beats someone else’s. What makes investing in fine art so appealing to investors of all sizes is that it isn’t correlated to other more popular asset classes like stocks or bonds. Here’s a look at the 40-year annual return correlation matrix comparing art against other popular asset classes.

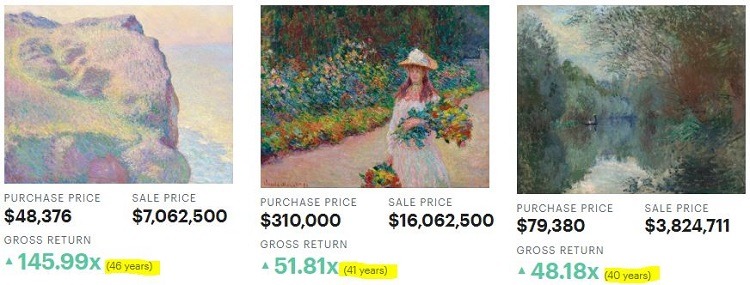

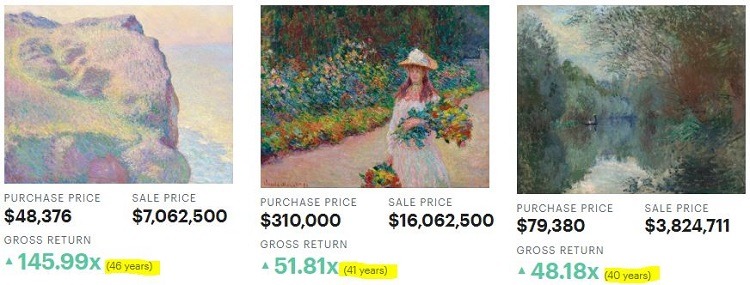

Whenever there is a financial crisis, various asset classes behave differently, but not predictably. In other words, when the equity market drops 30% because someone caught the Woohoo Flu, your fine art investment will continue to hold its value. Why is that? Probably because people with money know firsthand the importance of a buy-and-hold strategy. Just look at the sort of returns you can generate by going long a Monet piece of work for 40-plus years.

Art collectors have little choice but to hold for long periods of time. Historically, the global fine art market hasn’t had much liquidity.

The Global Art Market

In 2018, the global art market topped $67 billion with the United States, the United Kingdom, and China constituting 84% of that. About half of the total demand comes from the United States. Globally, the estimated value of all artwork in private hands exceeds $1.7 trillion.

Usually, art investors will get into the game by attending art auctions. Two auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s, handle 40% of all global artwork transactions. Not all art exhibits the same performance characteristics, and as you might guess, the more popular artists are the art market’s most stable segment.

In the previous line chart, we showed you the performance of the Artprice100 Index against the S&P 500 index and the Artprice Global Index. While the former outperformed the S&P 500 by a long shot, the latter didn’t. That’s because the Artprice100 Index consists only of the market’s most important artists, weighted for their average performances over the previous five years. These are names like Picasso, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Matisse, and Warhol. They produce what’s called “blue chip art.” They’re the best of the best, and they’re where all that outperformance comes from. As with stock indices, artists come and go. For example, here are the four changes made between 2016 and 2017.

- Joiners (incoming): Agnes Martin, Francis Picabia, Barbara Hepworth, Michelangelo Pistoletto

- Leavers (outgoing): Giorgio De Chirico, Alexej von Jawlensky, Paul Klee, Cindy Sherman

We’ve actually never heard of these names before, which is probably why we’re relegated to writing about fine art instead of owning it. However, that’s all changing now thanks to a startup called Masterworks. (Note that Masterworks paid the publisher of this article, but did not provide any input or commentary regarding the content of this article.)

About Masterworks

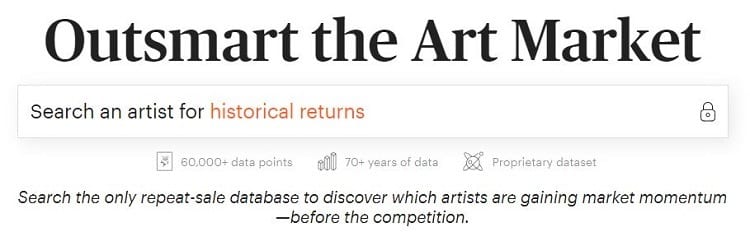

Founded in 2017, New Yawk startup Masterworks has taken in an undisclosed amount of funding to democratize the art world by making high-end art investments accessible to everyone. As you would expect, the experienced fund managers at Masterworks only invest in works of art they expect will appreciate – blue chip art along with some mid-late career artists like Banksy. How do you find out which paintings will perform better than others? The same way you answer any difficult question – with lots of big data. Masterworks has created a proprietary pricing database which goes back over 70 years, containing around 60,000 repeat-sale pairs (these are objects that have sold twice or more at public auction.) This helps them discover which artists are gaining market momentum before everyone else does.

Update 10/05/2021: Masterworks has raised $110 million in Series A funding at a valuation north of $1 billion as it looks to corner the market on bringing fine art exposure into people’s portfolios. This brings the company’s total funding to $110 million to date.

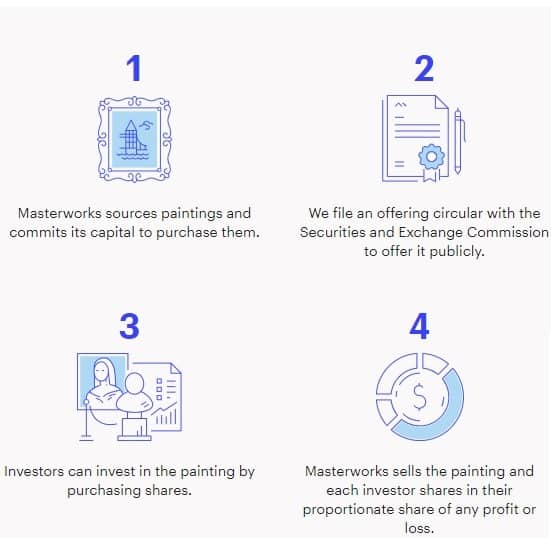

It’s not just about choosing the right painting, but about providing a platform that allows anyone to buy a fractional piece of art. Similar to a hedge fund, their fees are equal to a 1.5% annual management fee (paid in the form of equity) plus 20% of the profit if the painting increases in value. Here’s how it works.

The Fine Art Investment Process

After identifying a promising painting and then purchasing it, Masterworks files a Regulation A offering circular with the Securities and Exchange Commission. (We previously warned about Regulation A IPOs, something that doesn’t apply here because they’re being used as investment vehicles for artwork.) Once the offering is approved, anyone can purchase as shares in the offering which are priced as a normal share of stock would be. (Note to newbie investors, just because Google is priced at $1,400 doesn’t mean shares are expensive. The actual price of the shares is irrelevant to the underlying value. The same holds true here.)

Once everyone ponies up money and buys up all the shares, the long wait begins. If after seven years there is no other means for shareholders to sell or redeem their shares, Masterworks will endeavor to sell the painting on or before the ten-year anniversary of the offering, including considering sending the painting to auction. This provides some sort of liquidity because right now no public market currently exists for the securities Masterworks issues. That’s right. If you buy shares in a painting, they need to age like a fine wine. Even if you wanted to sell your shares, how would you find a buyer? Well, Masterworks is working on that too.

In the world of startups, there are secondary markets where employees with pre-IPO stock can go offer their shares up for sale to people who might be interested in them. As you can imagine, it’s not very liquid, but certainly better than no liquidity. Masterworks is currently working on a market for their art securities (it’s in beta), so that’s promising for those who are concerned about liquidity.

The usual caveats apply here. There is no guarantee you will receive more than you paid for your shares. There is also no guarantee you’ll be able to sell your shares in less than ten years’ time. Of course, that’s actually a good thing, because the “I want it all, and I want it now” mentality doesn’t work well when it comes to any sort of investing.

Before you get out your checkbook to make your first art investment, sit down and have a chat with someone at Masterworks first and ask questions about the piece of art in question. Use their extensive pricing database to research the artist you’re thinking about investing in.

Don’t invest in art unless you understand the time frames involved and are prepared to accept low levels of liquidity or no liquidity for up to ten years.

Conclusion

Investing in art isn’t just about diversifying your investment portfolio, it’s also fun. When you have some equity ownership in a work of art, you’ll probably become quite knowledgeable about the artist, and have an increased appreciation for the arts. It’s a great investment to make for the younger generation as it exposes them to artists they otherwise wouldn’t have known about and it demonstrates the value of having the discipline to buy and hold for long periods of time to reap above-average returns. For newbie investors, a lack of liquidity is often a good thing.