The big picture

What’s going on?

Heading down to your local crafts store and buying a canvas, some paints, and an easel is one way to invest in art – but not the way…

While art owners can’t trade paintings or sculptures like a stock or bond, art is an asset class unto itself. Investors typically describe assets like art as “alternative investments”: like an ugly duckling, they’re often ignored, but many still turn into beautiful investment swans.

Other alternative investments include real estate and typically high-risk hedge funds, crowdfunding, cryptocurrencies, private equity, and venture capital. But none of these are as aesthetically pleasing as the lie that makes us realize truth; after all, you can’t put bitcoin on your wall.

Why invest in art?

The short answer: diversification. The long answer: di-ver-si-fi-ca-tion.

A masterpiece of an investment portfolio should contain a wide selection of different assets (stocks, bonds, cash – and, yes, alternatives). The idea is that any losses in one area (say, stocks) should be offset by gains in others (bonds, for example).

The proportion of an investor’s portfolio that should be invested in art varies depending on individual investing goals and how much risk they’re willing or able to take.

According to the Wall Street Journal a few years ago, almost 8% of investors’ cash was held in “passion investments” like art. An economics professor noted for research that visualized artworks’ increasing value since 1875 believed that investing 10-20% of a portfolio in art was reasonable – but, as ever, it’s different (brush)strokes for different folks depending on individual circumstances.

Arty farty or arty smarty?

Art investors have a few ways to draw themselves into the market. They can buy artworks by relatively unknown, aspiring artists; classics by well-known, usually deceased, legends; or works by artists somewhere in between the two.

The barriers to investing in unknown artworks are relatively low, since it can be as simple as buying a friend’s piece or something you’ve taken a shine to at an art fair. In doing so, investors take on the risk of volatility, for better or worse: the price of the piece could rocket if its creator is discovered and critically lauded in the mainstream – or it could melt lower if the starving artist goes à rebours.

On the other hand, buying works by Old Masters or modern legends has historically been a trickier process, requiring investors to find their way into pretty exclusive auction houses – and shell out big bucks to get in on the action. Those that do, however, typically see the value of their artworks rise over time. Want to know how much? We’ll paint you a picture…

The value of top artworks rose by more than US stocks between 2000-2018

Pretty, right? Certainly for investors in Artprice100 works – these are the “blue chips”, i.e. the most stable segment of the art market, including works by the 100 best-performing artists at auction in the previous five years who had more than ten major works sold every year – think Monet, Picasso, Van Gogh, and the like.

The value of the top artworks rose by an average of 9% each year between 2000-2018, while the US stock market rose an average of 3%. The index tracking the value of the most important artists’ work is adjusted annually – as with a stock market index like the S&P 500 – with newly successful artists supplanting those falling from favor.

One point to keep in mind is the dividends – a share of profits – that companies in the S&P 500 payout to investors. Including dividends in the chart below would increase the S&P 500’s performance by around 50%. By comparison, investors don’t receive anything just for owning art – the payout only comes when they sell it on.

A frame of reference

The number of major art sales began falling months after the onset of the 2008 global financial crisis – and art’s value didn’t fall as much as stocks’ during the downturn. Research by economists shows that the price of high-end artworks doesn’t typically move in lockstep with the stock market – i.e. its correlation with markets is relatively low.

That may be because art isn’t subject to “systemic risk”: the notion that a market tends to behave as a single entity.

When the economy’s healthy, art changes hands frequently: there’s high “liquidity”. But while stock market investors often race to sell their assets when things head south, owners of expensive artworks (who tend to be pretty well off) usually don’t resort to desperately flogging their Rembrandts and Warhols for whatever they can get.

Instead, they simply hang onto them until the market becomes more favorable for selling.

Sketchy characters

Mind the sharp edges: let’s bring some of the risks of investing in art into the picture.

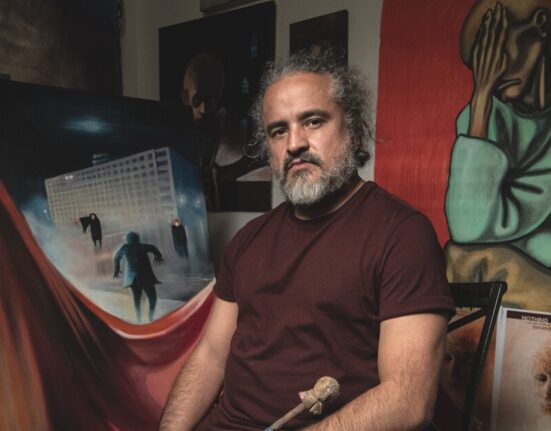

Counterfeits are a concern for many art investors. Naturally, a fake isn’t worth as much as an original, and its discovery as such can render an investment nearly worthless. Luckily, specialists focused on detecting forgeries and technology – including artificial intelligence – are working together to lower investors’ chances of getting duped. These days, forging art is much tougher than The Thomas Crown Affair made it out to be.

As with all assets, investors are subject to market fluctuations – for better or worse – affecting the value of their investments.

For example, the first few days of auction house Christie’s November 2018 sale of 20th-century works saw price tags 42% lower than a comparable event the year before, thanks to fewer high rollers from Asia splashing their cash. On the other hand, the same auction also saw the sale of the most expensive painting ever by a living artist. Take a bow, David Hockney…

Some investors are negative on art altogether – one common opinion is that it’s more guesswork than thoughtful investing, since tastes can change and most pieces lack any inherent value beyond the aesthetic (unlike companies’ stocks, the values of which are based on expected future profits).

Another concern art’s detractors highlight is that, while art’s typically a good way to preserve the value of money (fine art’s value, as demonstrated, tends to rise over time), it’s not so good when it comes to getting that cash back out, since major art sales are few and far between – and there’s no guarantee investors will find a bidder willing to pay the price they want.

Canvassing the industry

Pay the piper

For investors with serious cash lying around – think five, six, seven, even eight figures – buying a work of art outright is a legitimate option. Fancy a plate by Picasso? Yours for $5,000. An oil painting of his mistress? More like $155 million.

The process of buying and selling high-value art tends to be centered around a few big auction houses which hold regular public events as well as organizing private sales – Christie’s and Sotheby’s are two of the best known.

They act as brokers, and so get paid a double commission (from the buyer and seller) on any sale, just as if an investor bought or sold a company’s stock. But unlike stock market brokers, there’s not as much competition to keep fees low: in the UK, Christie’s charges buyers a fee of around 20% for its services.

Once investors have their artwork, they can display it at home or put it into storage for safe keeping. But some savvy investors might loan their art to a gallery. Sure, they risk damage (remember what Mr Bean did to Whistler’s Mother?) or theft (which is less likely than Hollywood would have you believe), but having it on display is a constant reminder of the art’s value – and might help it sell on for a higher price in the future.

Buying shares of art

If the above seems a bit beyond your reach (at least right now), don’t worry. Thanks to advances in technology – including blockchain – these days, investors who don’t have millions going spare can invest in fine art, too.

Just as robo-advisors have helped to democratize access to financial advice and portfolio-based investing, there are platforms that allow investors who aren’t filthy rich to own a share of an artwork and enjoy access to its investment potential for only a few hundred or thousand dollars.

By and large, art investment platforms work in fairly similar ways. Some buy an individual artwork themselves, then create and list shares that other investors can buy – making money by charging a fee for managing the process, as well as for storing and insuring the art on investors’ behalf.

When the piece is eventually sold, platforms tend to take a share of any profit, too. Other platforms may not buy art directly, instead connecting investors with owners who might want to sell a fraction of their artworks.

There are also platforms focused on allowing investors to buy and trade works by as-yet-undiscovered contemporary artists. Artists can sell shares of their works and thereafter distribute income from any fees received if the pieces are loaned out to galleries or sold outright.

Should the art become more valuable over time, investors who got in early can paint the town red with their profits.

Making your masterpiece

Before we let you loose with your own investing palette, here are four key things to think about before buying, according to art investment platform Masterworks:

The historical importance of the artist

- Is the artist well recognized by major institutions or art scholars?

- If the artist is deceased, do they have an estate or trust to look out for their works’ best interests – helping to preserve and increase their value?

- Is the artist part of a movement? The Impressionist movement, for example, raised the profiles of many artists beyond just Monet and Degas.

- Is the artist recognized and highly rated by import dealers and critics, and therefore likely to have good resale value?

Art first, artist second…

- “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet” – just because a piece is by a famous artist, that doesn’t guarantee it’s not a dud.

- Much of the work produced by Picasso, for example, isn’t considered as important as his blockbuster pieces (hence the relatively cheap ceramics mentioned above).

Access is the bargain to be had

- Do you have access to networks of dealers who buy and sell the art you’re interested in?

- Access may matter more than price – so it might be worth paying a little over the odds to buy art that could lead to more opportunities, both buying and selling, down the line.

- Since the value of the most well-known art tends to rise over time, that might not be quite as crazy a prospect as it sounds. Think, for example, of “dollar-cost averaging” when buying stocks.

Don’t spread yourself too thin

- It goes against almost all investment advice. But with art, the thinking is that when buying works outright (as opposed to a share of one), most investors are better off spending their money on one or two expensive pieces rather than a handful of cheaper ones.

- Highly rated, critically acclaimed work tends to be pricier. And it follows that a more expensive piece has a greater chance of being considered important – and of subsequently increasing in value over time.

- The closest parallels in traditional asset classes are probably tech stocks, which are among the biggest on the market and which saw their prices rise more than most other stocks’ throughout 2018. On the other hand, when markets fell, those very same companies bore the brunt of the decline…

Get the picture?

In this guide, we’ve lit up:

- The real deal about art investing and why people do it

- How art investments have performed compared to the stock market

- Ways to invest in art – buying either a whole work or a share of one

- What to think about before buying art

This guide was produced in partnership with Masterworks.