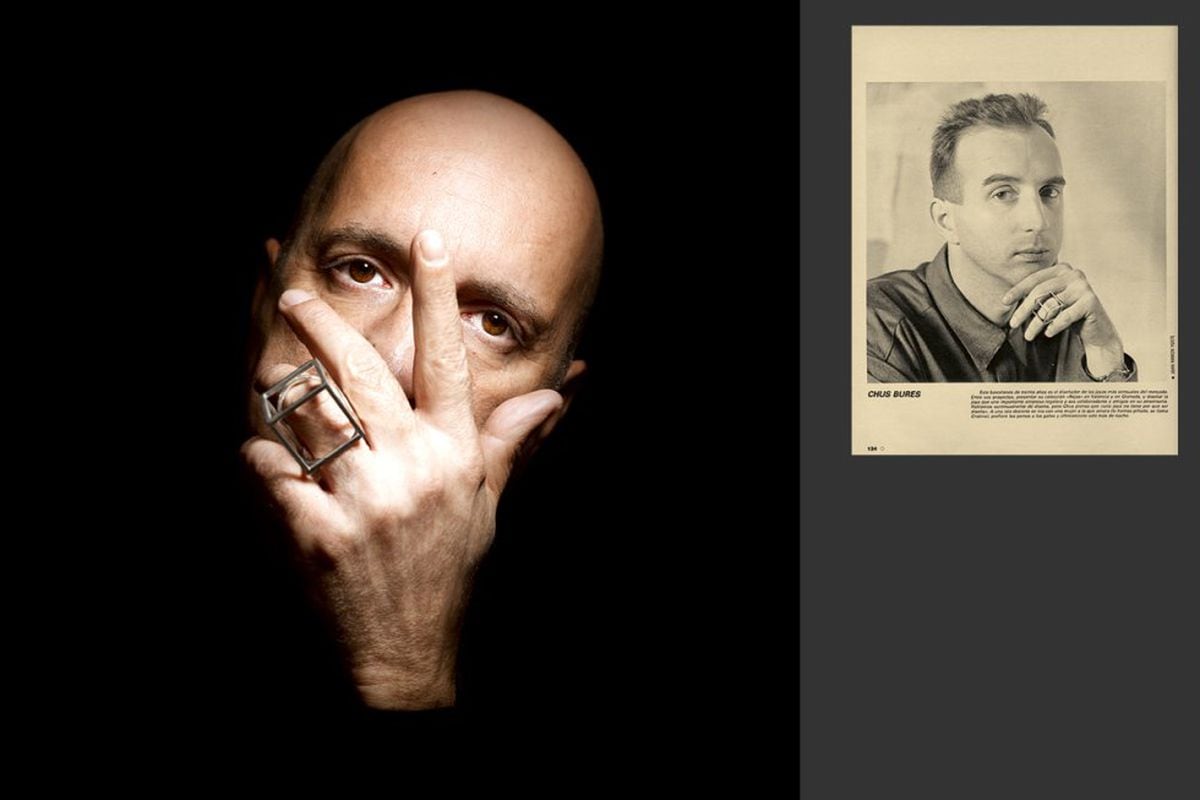

When the famous art gallerist Juana de Aizpuru, a pioneer of contemporary art collecting in Spain, made room for him in between exhibitions by renowned artists, a young Chus Burés, recently arrived from Barcelona to Madrid, could not imagine that the opportunity to show his first jewels would take him to the same heights as Louise Bourgeois or Carmen Herrera, two artists with whom he began to collaborate immediately. It was 1985, a time of creative explosion in the Spanish capital, and Burés, who was then 22 years old, stood out as a restless, effervescent talent, who decades later has refined his work with maturity, but with identical nonconformity.

Collectors from around the world, especially from the United States and France, own his work, and now, coinciding with an exhibition in his Madrid studio developed in collaboration with the architect and Columbia University professor Juan Herreros, he is exhibiting his most creative side (“ less constrained by the requirements of the market,” he explains) at the Americas Society in New York: he is the first Spanish artist to whom the society opens its rooms. The New York exhibition is titled Art as ornament: Chus Burés and Latin American Artists in Collaboration, which runs until May 18, 2024. The selection of Burés jewelry is the epilogue of an interesting two-part exhibition titled Eldorado: Myths of Gold, with reviews and reinterpretations by more than 70 artists from Latin America.

Burés’ relationship with the United States dates back to the mid-1980s: the creator has always been precocious and pioneering at the same time. Exhibited in the institution’s library, Burés’s jewels review not only his career, but also the main trends in Latin American art of recent decades. From his collaboration with the kinetic artist Jesús Rafael Soto to the consecrated Carmen Herrera, and also including the Cuban Kcho, with whom he designed two beautiful allegories of the desire to flee the island: a winged boat and a branch ending in the paddle of an oar. Other artists represented in Art as Ornament are Antonio Asís, Tony Bechara, Carlos Cruz-Díez, Sérvulo Esmeraldo, Macaparana, Marie Orensanz, to name just a few.

“This exhibition shows the most experimental part of my work,” explains Burés in New York, one of the three cities where he operates (the others are Madrid and Paris). “Working with artists allows you to avoid parameters such as cost or investment that do determine the creation of jewelry intended for the market. You can play with the most experimental part, and there is a collection that seeks precisely this type of jewelry, that wants something original. It is a market of demanding clients who value the idea, the pure creation, because what interests me is the exchange, the dialogue with the artist.” That, and his obsession “for making wearable art,” explains his commitment to conceptually elevate the jewelry he creates.

Burés has earned a loyal legion of collectors, especially in the United States and France. In Spain, his work is very successful in Catalonia. His relationship with his clients-friends also goes beyond the usual commercial relationship to become another celebration of art. An elegant book that can be leafed through at the New York exhibition portrays his creations, worn, as if they were decorations rather than jewels, by artists and collector friends. With photographs by Andrés Serrano and Antoine d’Agata, the volume begins with the 2015 image that immortalized a venerable Carmen Herrera as a matriarch, with the geometric brooch that she designed with Burés closing her shawl. The book is also a celebration of friendship, or at least the special relationship of intimacy that is forged between creators.

After studying interior design in Barcelona, his hometown, and learning the jewelry trade in various workshops in the Catalan capital and in Madrid, Burés embraced unusual and unconventional materials, such as industrial waste, metals and recyclable objects of various shapes and origins. But the exhibition in Juana de Aizpuru’s gallery, a selection of silver works, made him abandon experimentation, even though the drive to innovate has never abandoned him. He defines himself as a “multi-material sculptor.” In 1985, film director Pedro Almodóvar commissioned him to create the hairpin and murder weapon for his film Matador, a silver treble clef inspired by Andalusian window grilles— that opened the doors to the international market. These days, his studio in the New York neighborhood of Chelsea is one of those secret and coveted addresses that are passed from hand to hand among his close circle.

Five years later, in 1990, Burés definitively sealed his love relationship with New York, with his contribution to the wedding trousseau of a unique marriage: the nuptials of the Statue of Liberty and the Columbus Monument in Barcelona, a project by the Catalan artist Antoni Miralda in the Spanish pavilion at the 44th Venice Art Biennale. Since that wedding, Burés has felt like a real New Yorker. His latest exhibition in the heart of Manhattan confirms that he is.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition