As you’re reading this, someone is probably asking MacKenzie Scott for money. Ever since she divorced Jeff Bezos, winning $38.3 billion in the settlement, Scott has given away $14 billion to some 1,600 nonprofits, selecting each one herself with input from advisors. But for her latest round of monster-size charitable giving, she announced an open call for applications to receive $1 million in unrestricted operating gifts from her personal foundation, Yield Giving. Think of it as America’s Next Top Do-Gooder. Of the 6,353 entries received for the peer review process, 250 will be selected early next year.

“Peer review is the most legit process, but now everyone is reading everyone else’s application, and it’s kind of like Squid Game,” says a grant writer for an arts nonprofit. In other words, it’s tough out there for a grant seeker, and also, conversely, for the funders setting the dollar figures. The difference between a yes and a no is a fine line that’s undergoing yet another evolution as more high-net-worth individuals enter the arena.

Households with at least $1 million in investments gave an average of $34,917 to charity in 2022, rising 19 percent from $29,269 in 2017, according to this year’s Bank of America Study of Philanthropy. And that’s to say nothing of those much higher up the food chain. “It’s a different landscape. There are a lot of very wealthy people,” says Esther McGowan, director of development at Aperture, who has worked in fundraising for more than two decades. “There wasn’t as much access to billionaires as there is now.”

More From Town & Country

More people means more complications. And so, like watching television, dating online, and buying seltzer, getting money has become an obstacle course of options, decisions, and tricky maneuvers, an Amazing Race for Billions. There’s an axiom in fundraising that if you get a meeting you are 90 percent of the way to the gift. But nowadays getting to that point is like walking through the Hall of Mirrors to visit the Queen’s Chamber—in heels, holding two smartphones Zooming and FaceTiming. The courtship between donor and beneficiary has become a tricky dance rife with risks—a poorly worded overture, a clumsy decline, a Teams slip-up when you thought you were muted—and consequences for all.

Of course, every meeting is different, and every ask is bespoke. But according to dozens of wealthy patrons and development professionals across the nonprofit spectrum, one rule still applies: Ask elegantly. Respond in kind. Every little step along the way counts. And when you meet face to face for that final rendezvous, reach deep inside and discover your inner Charlotte Rampling. “It’s a seduction,” says a generous donor in New York. “It should feel good for both parties.” Let the games begin.

Swipe Left Like Tech

The old school model of giving—the fusty foundation that just wrote checks to various causes—is under review by TikTok-generation technocrats. “We are seeing engagement in the next generation, under age of 42,” says Jennifer Chandler, head of philanthropic solutions at Bank of America Private Bank. “They want to see the benefit of their gift. They are very engaged and thoughtful.”

People who made money in the past two decades want to measure their impact. It’s what drove Silicon Valley’s interest in the effective altruism movement, which took a hit after its poster boy, Sam Bankman-Fried, was exposed as a crook but remains an attractive framework in the tech world. The Palo Alto elite pride themselves on knowing every last detail of where their charitable contributions are going, down to whether the coffee at the luncheon is bird-friendly. Good luck if it isn’t. Data is their lingua franca, a feel-good tool to track progress on targeted goals.

“When I started, people believed in institutions more,” says a major gifts officer at an elite university. “They were ready to make an investment they believed in, especially the more seasoned alums. A lot of the younger alums are mission-driven and get into the specific things and a portfolio that includes exactly what they care about.”

Polite persistence pays off, though. “I always say a nonresponse is not a no,” says this person, who recently brokered a multimillion-dollar contribution from a wealthy alum. “If you send an email and they don’t write back, 95 percent of the time they’re just too busy to see it. If I think they’re philanthropists and have capacity, it’s my job to not give up until someone actively says, ‘This is not important to me.’ If you told me that this donor would donate so much money 12 years ago, I wouldn’t have believed you.”

Stall with Flacks

Like the endangered snow leopard, which they started a foundation to save, the wealthy are nearly impossible to see in their natural habitat. More likely you’ll be interacting with one of their many gatekeepers. And now there are more of them, too. “People are more closed off to outreach,” McGowan says. “There used to be a way where you could just write a letter. Now it’s a closed process with an advisory team, and you have to find a way for advisors to know about you.”

Another nonprofit executive says, “Often the benefactor wants a buffer. They don’t want to be pitched, they don’t have time to learn about it, and that advisor serves as eyes and ears.” These counselors, meanwhile, are shaking in their Tod’s loafers, anxious that they might have turned away the next Wes Moore, who was the chief executive of the Robin Hood Foundation before he became Maryland’s governor and a rising star in the Democratic Party (see page 56). “Your job is to listen, learn, understand how things have impact, and then funnel money to the people who make things happen,” says one advisor to a major donor.

Scoped Out

In our era of emergency cat surgery GoFundMe pleas, when even the CVS cashier has a tip jar, we are awash in asks, especially when you’re known for your generosity. “We make sure our team responds to every request,” says Brent Ridge, the former vice president of Healthy Living at Martha Stewart Omnimedia. He and his husband, the best-selling author Josh Kilmer-Purcell, co-founded the successful beauty and lifestyle brand Beekman 1802 about 15 years ago, and as it (and their celebrity) grew, so did the overtures for charitable contributions. When they started the company, along with their business plan they wrote a charitable mission statement outlining the causes they’d support should they have the opportunity. Every year they set a budget. That goes for both their company and their personal giving.

“When we decline, it’s because it’s outside the scope of that charitable mission,” Kilmer-Purcell says. “It makes the asker not feel unworthy. We are fairly charitable people, but a budget makes it so much easier to keep within a range.”

Otherwise Engaged

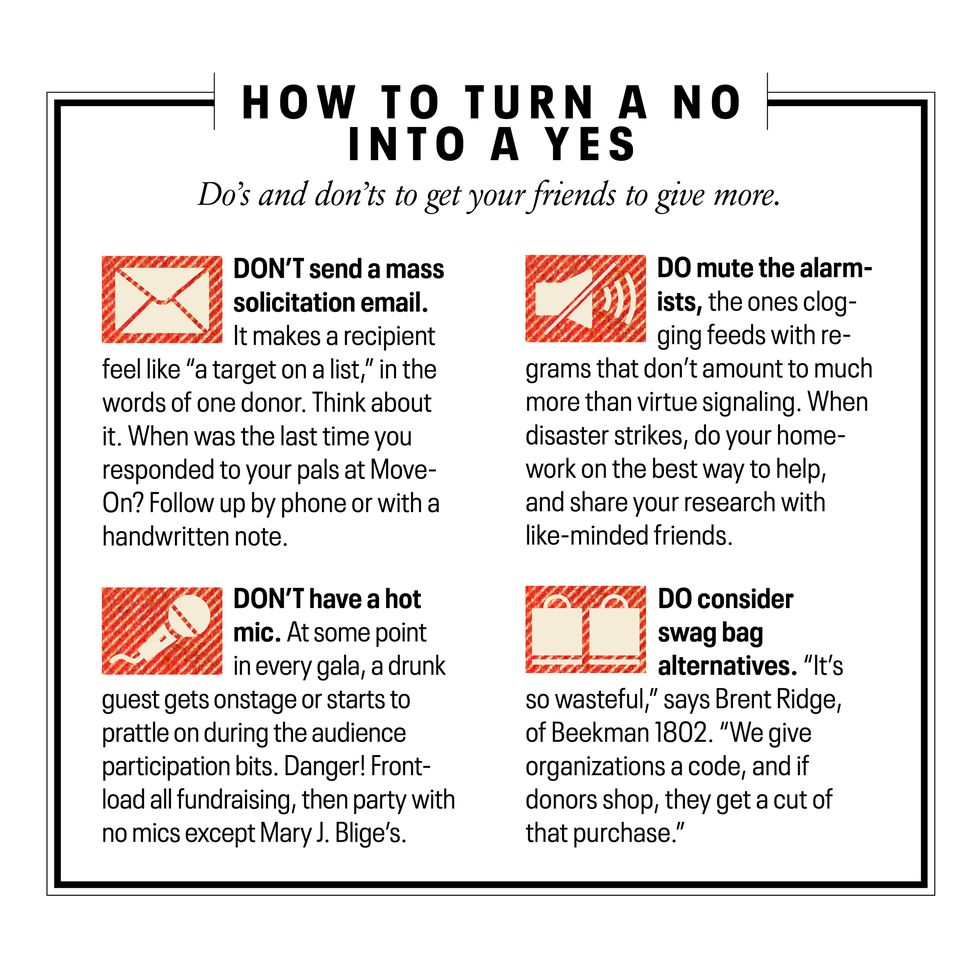

The most common form of entreaty for charitable dollars is the gala invitation. The pandemic put them on hold—or made them (shudder) virtual—but the good old-fashioned rubber chicken dinner at Cipriani or (shudder) Guastavino’s is back with a vengeance. Fortunately, event producers made a few tweaks in the interregnum. “It’s been great to start fresh and new. A lot of the wasteful stuff has been done away with,” says Chris O’Shea, co-founder of Washington, DC’s C2Auctions, which specializes in support for nonprofit galas and auctions. “A silent auction used to offer an average of 150 items. Now it’s 50. A live auction that was 15 lots is now five. I’ve seen many more opportunities for socializing at the party after the fundraising.”

Some things, however, haven’t changed, says one half of a couple often seen on the benefit circuit: “We say we have a prior commitment, and then privately joke that our prior commitment is to not go to an event.”

This story appears in the November 2023 issue of Town & Country, with the headline “Just Say No.” SUBSCRIBE NOW