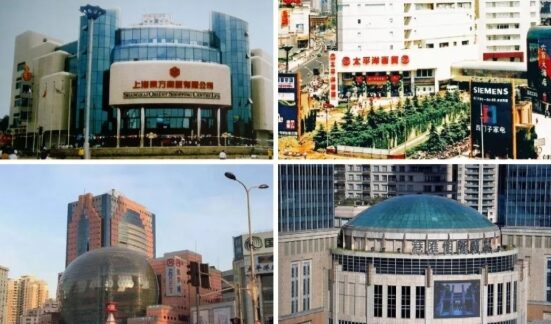

Since its founding in 1930, Moffett Field has had multiple incarnations. It was originally a U.S. Navy airship base, and its massive dirigible hangars – some of the largest free-standing structures in the world – still endure, emblems of the Bay Area that are nearly as iconic to residents as the Golden Gate Bridge or Coit Tower.

Following the decline in airship demand, Moffett was a training facility for carrier pilots; then in 1994, the field was shuttered as a Naval air station and transferred to the NASA Ames Research Center. Now, it’s poised for another role: the Berkeley Space Center. Driven by the University of California, Berkeley and supported by NASA Ames and private technology investors, the new venture will serve as a kind of super incubator for all things aerospace. The vision: 36 acres of land leased from NASA, 1.4 million square feet of research space, and a supporting investment of $2 billion.

“We’re bringing together three powerful elements – government, academia, and private industry,” said Darek DeFreece ’93, the Center’s executive director and the former president of the California Alumni Association. “Separately, each can create great things. But together, they can create heroic things.”

Alexandre Bayen, a UC Berkeley professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences and an associate provost for the Moffett Field development program, said the Space Center’s location isn’t fortuitous – it could only have happened at Moffett Field. He cited the reasons: the necessary room and much of the basic infrastructure already exists at Moffett; it is operated under the auspices of Earth’s leading space agency; it is in Silicon Valley, the planet’s central ganglion for technological expertise and venture capital; and it is a short commute from UC Berkeley, one of the world’s leading research universities.

“We’re going to combine the aerospace portfolio with areas not classically associated with the field – AI, machine learning, and data science,” said Bayen. “This is where we’ll build the aerospace curriculum of tomorrow.”

While the design of bigger, more powerful, and more sophisticated spacecraft may well be a focal point of research at the Center, the project’s scope encompasses a wider reach. Deep space exploration isn’t just about propulsion systems, Bayen said.

“A big issue is simply maintaining life in space,” Bayen said. “How do you create and support supply chains? If you want to grow your own food, you’ll need to develop radiation-resistant plants. How do you do that? Additive manufacturing – 3D printing – is developing rapidly, and it’s certain to play an important role in space, for a wide variety of applications. Printing human organs, for example – it’s easier to do in zero gravity, in space, than it is on Earth.”

The Space Center will address near space as well as outer space. The rapid development and deployment of drone aircraft already has had a profound impact on everything from warfare to the monitoring of climate change impacts, and their applications will only expand and accelerate, said Bayen. He sees the Center as a future leader in the field.

“Major change is coming in the next 10 years with pilotless aircraft and electric vertical aviation,” Bayen said. “Think about wildfire fighting. Right now, the most dangerous job in that dangerous profession is air attack – dropping water and retardant on the fires. I think you’ll see pilotless aircraft dominating there in the coming years. Medical evacuation from disaster zones is another area they’ll be deployed.”

While drones will reduce risk and increase efficiency, they will also make airspace far more crowded. That means the architecture of airspace must be completely redesigned, said Bayen – and it will require a significant investment in AI and machine learning to do it. He emphasized the Berkeley Space Center will have all the necessary components for the job: state-of-the-art facilities, ample private sector funding, and technological expertise.

The Center’s development will proceed in three phases, said DeFreece. The first is entitlement (i.e., obtaining necessary permits), which will cost about $20 million. The “horizontal” phase will encompass power, water, and sewage system construction and cost $80 to $200 million. The “vertical” and final phase will consist of the necessary buildings. They’ll go up as the market dictates, said DeFreece.

“We’re well into entitlement now, and if the demand is there, we could proceed through the vertical phase in six years,” he said.

For DeFreece, the Center is the realization of a personal dream as well as a professional capstone; he had long felt that a collaboration among UC Berkeley, Silicon Valley, and NASA would yield a sum vastly greater than its parts. Four years ago, at the direction of UC Berkeley’s Office of the Chief Financial Officer, he met at a Peet’s coffee shop with NASA Ames representatives to discuss the possibility of a Moffett Field partnership.

“Looking back, it was a classic Silicon Valley start-up origin story – meeting at a coffee shop, deep conversations, back-of-the-envelope calculations,” he said. “I have the feeling that the Space Center is going to finally put a pin in the center of Silicon Valley. Because, really, where is the Valley’s center? Google? Apple? Meta? They are all powerful and influential, but they’re independent companies. The Space Center, though, is a collaboration of private industry, the academy, and government for what is literally the highest possible technological goal. It exemplifies Silicon Valley. So that’s where you put the pin.”