Tracey Emin carried around a giant tote decades before enormous handbags were fashionable. Back then, in the 1990s, when she was emerging as a gale-like force in a loosely affiliated group that came to be known as the Young British Artists, people often asked her — journalists, fans on London streets — What do you keep in there? She says the real answer was usually a sketch pad, her daily ration of three packs of Marlboro Lights, six Stella Artois beers and a fifth of brandy, but it was easier to say she needed a bag big enough to haul all her insecurities.

“Ironic now, thinking about that, right?” she says, in her soft, working-class-accent, on a chilly afternoon, as she tries to find a comfortable position on a sofa in her recently renovated townhouse on Fitzroy Square, a genteel, central-London pocket that was once home to both Virginia Woolf and George Bernard Shaw. She reaches into the large canvas carryall at her feet to pull out a plastic pouch of urine, which is connected under her loose cotton shift by a long tube to a stoma in her abdomen. She waves it slightly, a white flag, maybe, though because this is Emin, surrender has never been an option. “Now, what I have in there is a bag of piss.”

Three years ago, at age 56, in the thick of the pandemic, she went to her gynecologist because she had fallen in love with a New York-based collector and critic, and, after 10 years of celibacy, was considering penetrative sex. Instead, she received a diagnosis of very aggressive bladder cancer and days later, had radical surgery to remove that organ as well as her uterus, her ureter, some of her colon, a slew of lymph nodes and half her vagina. “I made them leave my clitoris,” she says.

On Nov. 4, her first New York solo show in seven years, “Tracey Emin: Lovers Grave,” is set to open at the new Upper East Side outpost of White Cube, the London-based international gallery that has always represented her, and despite the pressures of that and her health, she seems at rueful peace. Her equanimity is unsurprising: surviving intense turmoil — that which has been randomly doled out as well as that of her own creation — is what Emin does best, what she’s always done. Only Damien Hirst has had more fame among living British artists, but despite critics lashing Hirst and Emin together as the Y.B.A.s (along with Sarah Lucas, Gary Hume and several others), his work is a depersonalized mélange of dead animals floating in formaldehyde, spin art, a bejeweled skull and multicolor dots. Emin’s oeuvre has only ever orbited one thing: herself, in her many mournful, voluptuous, warty, wild and furious incarnations.

In paintings, installations, quilts, monoprints, films, photographs, bronzes, neons and reams of text, the membrane between her work and her life has been not merely porous, but nonexistent. From her ragged childhood and dangerous underage sex with adult men in the bedraggled streets of seaside Margate, 90 minutes by train east of London, stints of homelessness, rapes (one at 13), two abortions, and now her illness, her traumas and thorny romantic entanglements are writ loud in her art.

The early installations that seared her into the public imagination were “Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995,” a tent within which she had embroidered the 102 names of lovers, family members and two numbered aborted fetuses — part of the seminal 1997 “Sensation’’ show in London — and “My Bed” (1998), a recreation of her life after a post-breakup psychological breakdown, complete with filthy sheets, empty vodka bottles and underwear smeared in menstrual blood, but her corpus over the decades has been varied, all of it executed at full emotional volume.

Over the years, her public persona often overshadowed her prodigious output, especially in Britain, where she was stalked by rapacious tabloids. Critics carped about her solipsistic exhibitionism, the times she fell out of a taxi drunk, how she sacrificed credibility by becoming a muse for the clothing designer Vivienne Westwood (a notion that in our era of boundaryless collaborations between artists and the fashion world seems quaint). Some even speculated that her debauched life was a meta-gag, a performance of self.

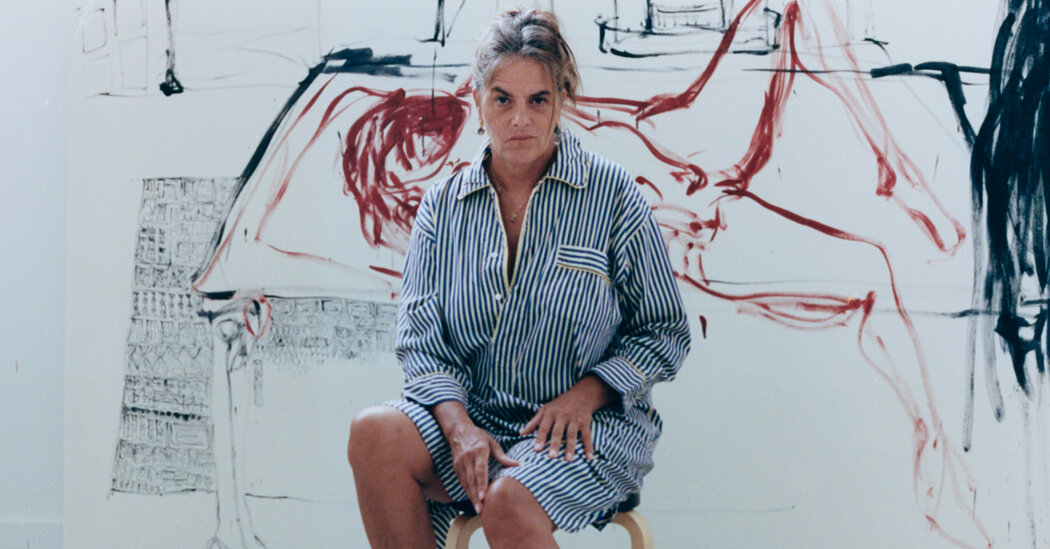

In that pre-#MeToo world, her rage over her sexual abuse and honesty about her abortions seemed to strike them as, well, a bit dreary, or at least repetitive. When they did look at the paintings — spidery nudes, often couples entwined amid or atop slashes of vivid abstraction — some dismissed them as derivative of her acknowledged heroes, Egon Schiele and Edvard Munch.

It rankled some critics that she was volcanically successful, with collectors including Madonna and Elton John, and Tate eagerly acquiring her work. If she was going to make her art her life and her life her art, critics reasoned, wasn’t it fair to critique the way she behaved? When “Everyone I Have Ever Slept With” was incinerated in a 2004 warehouse fire, with other important works owned by the Y.B.A. patron Charles Saatchi, there was a geyser of schadenfreude, to which she responded with her hurt stripped bare: “They laugh at a disaster like a fire. It is just not fair and it’s not funny and it’s not polite and it’s bad manners.”

Through it all, the New York art world seemed confused by her, and museum curators here largely ignored her. (One of the few Emins owned by the Museum of Modern Art is a series she collaborated on with Louise Bourgeois.) She never seemed a comfortable fit at her New York gallery, Lehmann Maupin, with which she parted ways in 2017.

“In England, she and the Y.B.A.s were part of the DNA, part of the post-Thatcher revolution, and their growth was incredibly meaningful,” says Jay Jopling, founder of White Cube, in whose tiny original Duke Street gallery many of the group first showed. But when Tracey was shown in the U.S. in the early 2010s, “she was on the cusp of returning to a more classical practice,” he said. “No one quite knew whether to regard her as a conceptual artist or a painter and sculptor.”

But there often was also a whiff of misogyny in reviews of a woman who depicted herself legs open, who asked in pink neon “Is Anal Sex Legal?” and who spelled out on a 6 by 8.5 foot appliqué blanket I DO NOT EXPECT TO BE A MOTHER BUT I DO EXPECT TO DIE ALONE. And then there was the issue of class, the thrumming subtext of her work and her life. Forever the central struggle of British society, its complexities never have resonated in the U.S. the way race does. In 2009, two years after Emin represented Britain at the Venice Biennale, Nancy Spector, then the chief curator of the Guggenheim Museum, dismissed her in The New York Times as “having a lot in common with the sort of reality television that came out of Great Britain.”

But the world has changed, as has she. In person she remains alternately gentle and fierce, self-loving and self-loathing, but her famed restlessness seems subtly becalmed. Cancer and age have softened her, she says. She quit drinking two days before her surgery, which “has changed me inside and out.” The romantic relationship that led to her diagnosis has endured.

Still, one thing remains: She continues to create at a furious pace. She didn’t mind not being able to work as she recovered — her “barbed-wire variety” stitches made it hard even to sit up — because she had been working so assiduously before her diagnosis, as though her body knew it would soon be unable to, she says. Emin is now painting and sculpting almost exclusively. Except for her creative director, Harry Weller, 32, who has been with her since he was 18 and often stands near her as she works, she has no assistants.

“The medium has changed,” says Jopling, 60, “but not the underlying ideas, and not her purity. I don’t know a single other artist who is that pure.” Almost all the 25 or so pieces at White Cube’s new space, which occupies a 1930s former bank building on Madison Avenue, are acrylics, some as big as 6-by-9 feet. In icy blues and gashes of red, with scrawled figures writhing in ecstasy or pain, they embody the liminal space of her current existence — post-cancer, making uneasy peace with a new body, in love.

Her awareness of her mortality also has intensified her other great passion: real estate, not as an investment, but to create a world to wrap around herself. In addition to her grand residence in Fitzroy Square, which she bought in 2020, she’s long had a studio in the south of France, and an apartment overlooking Stuyvesant Square Park in Manhattan, which she rarely visits. “I think my love of property is a matter of having so little growing up, being jammed together, being homeless.” she says.

But after the 2016 death of her mother, who spent half her life in Margate, Emin has poured a great deal of passion into transforming her hometown of about 63,000, a former summer resort that for decades has been riven with poverty and opiate abuse, into a locus for artists. Even though Margate is the site of her childhood degradations, she “can’t let the place go.” Aided by the opening of the Chipperfield-designed gallery Turner Contemporary in 2011 —J.M.W. Turner, the Romantic watercolorist, lived and painted there for 20 years in a boardinghouse on the rocky site — she has been an unwavering civic booster, lately spending most of her time there.

In 2017, she and a former lover, the gallerist Carl Freedman, bought and split a 26,000-square-foot former newspaper printing plant, which now houses both Freedman’s two-story space and, through a separate entrance, her gigantic, airy studio and elegant living quarters, which she intends to leave, along with several other contiguous studio spaces she has bought in the compound, as a public museum after her death. Long passionate about open-sea swimming, she built a full-size ground-floor lap pool for when the weather grows raw. She also recently bought three five-story houses nearby that she is redoing as a primary residence, guesthouse and yet another studio.

These days, Margate, where in 1921 T.S. Eliot wrote Part III of “The Waste Land ” while recuperating from a mental collapse (“On Margate Sands./I can connect/Nothing with nothing.”) has struck a balance that often eludes gentrifying areas. It retains its earthy demeanor, with middle-aged daytripping couples bar-hopping, but the rickety, winsome vernacular houses on twisting lanes have attracted many young, largely working-class artists and craftspeople, affordable restaurants and thrift shops. Unlike, say, East London’s Shoreditch, or its spiritual progenitor, Williamsburg, Brooklyn, the town isn’t — at least not yet — a place for trust-funders or tech bros hoping to pass for bohemians.

Margate has been called Emin’s Marfa, but unlike that Texas desert art mecca begun in the 1980s by the minimalist Donald Judd, Margate was no blank slate. Nearly 40 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, and once you wander beyond the old town, the wind blows trash around dilapidated buildings. To hurry the metamorphosis, in 2022, Emin began renovating a vacant bathhouse that now houses 11 subsidized studios for established artists who have moved to Margate. There is also an 18-month residency program for up to a dozen emerging talents; the current crop includes students from Brooklyn, Uganda and the Isle of Wight.

But even amid real estate deals and construction that never seems to end, and the anxiety-producing scans, the White Cube New York opening crowds her thoughts. On good days, she believes she deserves a fresh critical appraisal in a city that has never quite known where she fits in — and some distance from her earlier work and her earlier self. “I think people weren’t sure that I was sincere, and I hope now maybe they’ll see that I am, that I’ve always been.”

If that doesn’t come to pass with this New York show, she’ll likely be wounded, as she always is by rejection, but “art is everything to me,” she says, and she’ll keep making it. “I’ve always been judged by the way I live, and really, just the bad bits of it. I know that’s rolled up in what I do, having no distance. But so much has changed. You have to wonder what people will see this time when they look.”

Tracey Emin: Lovers Grave

Nov. 4 through Jan. 13, 2024, White Cube New York, 1002 Madison Avenue, Manhattan; (212) 750-4232; whitecube.com/exhibitions/new-york.