The News spoke with six visual artists — all of whom represent diverse identities under the Asian American umbrella, as well as use diverse art forms — about how their Asian-ness shapes their work.

From Slavic music and customer service to auto-consumption and land reform laws, these creatives integrate different, personal experiences with their work in all shapes and forms.

THISBE WU ’26: Inspiration is everywhere — from portraits to Slavic music to Alice Neel.

Comic books were Thisbe Wu’s ’26 first source of inspiration. As a child, she was drawn to creativity in all forms, whether it be performances, galleries, films or museums. Having experimented with portraiture, oil painting and sculptures, she now considers herself a printmaker.

She’s always been drawn to capturing the people around her, she said. Her favorite piece — a portrait that she painted as a high school senior of her dad and his brother as children — is a testament to this love of representing friends and family and her art.

Growing up in New York City, the proportions of a face she learned to draw were always based on white examples. She found “joy” in painting family members and learning how to “truthfully and authentically” portray people who look like her, both in a technical sense and in an emotional sense.

Over spring break, Thisbe visited the National Museum of Fine Arts in Manila over spring break and saw portraits of Filipinos, painted by Filipinos in a “Western 19th century style.” Looking at the way these artists had rendered the Asian faces, she felt them working through the same technical challenges of light and shadow.

“It was really magical to see this history and lineage and tradition of painting that I hadn’t encountered before,” said Thisbe. “And see Asian faces being represented so beautifully and with such care and respect when a lot of the paintings of Asian people from that era that are by Western artists are really orientalist.”

While her Chinese heritage informs Thisbe’s art, it’s not a defining feature of her work. At a Balkan camp in upstate New York last summer, she leant the doumbek and tambura. Now, on campus, her role as director of the Yale Slavic Chorus has become an important part of her life — and her art.

Music is a huge source of inspiration for Thisbe. Her taste ranges from Mozart to The Cure to The Cranberries. Specifically, she’s been a fan of Mitsuko Uchida since high school.

“There are videos of Mitsuko online, but seeing it in real life was really, really incredible,” said Thisbe, recounting a concert experience. “She has a really unconventional way of conducting. She doesn’t give a beat pattern. It’s all about the push and pull of the sound and the emotion of the sound and the tension and release.”

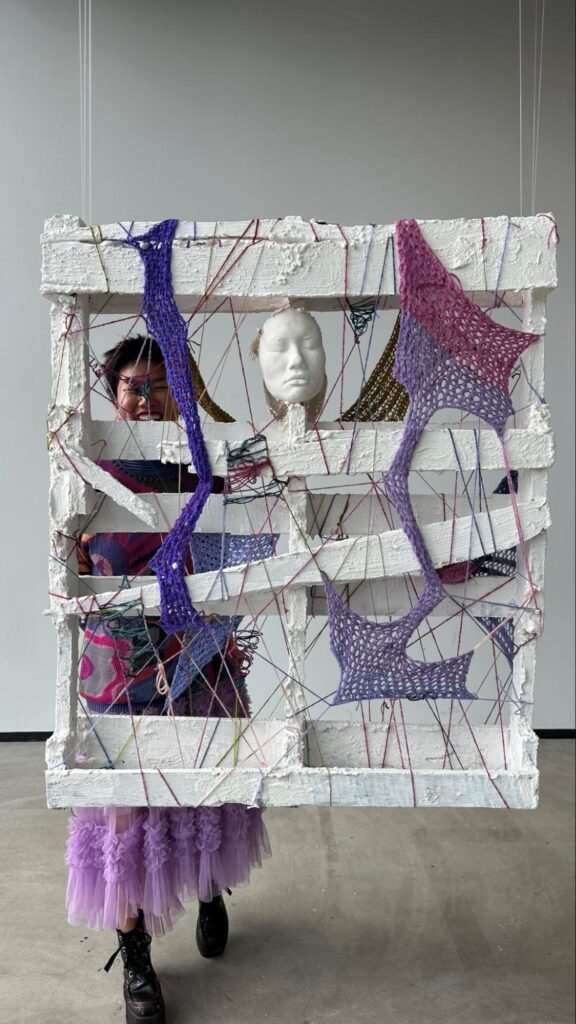

CLAIRE CHEY ART ’25: Sex with ghosts and other artistic provocations

Claire paints bodies. She thinks about consumption, self-consumption, pleasure, trauma and dreams.

Before coming to Yale, Claire spent four years trying to “make it” as an artist in Korea. She worked images of food, comparing that to the sexualization and consumption of women, often dealing with violent images.

During her first exhibit at a gallery-café in Seoul, she displayed two large paintings of women’s bodies. Customers walked out after seeing her work, considered “too provocative and sexual.” The paintings were soon covered with curtains.

At her first solo show, a professor from a well-known Korean art school walked out when she explained that a painting was about sexual violence and UTIs.

Now at Yale, Claire feels free to take her work in new directions and push boundaries without fear of immediate judgment. She’s become more interested in what happens within and how trauma functions to shape desires.

“As a woman, when you’re taught that your body is up for consumption, how do you deal with that? How do you live with yourself when you’re alone? Or how do you find desire?” said Claire. “And I know that’s going to be a tricky murky area, but I think that’s where my interest is, kind of deconstructing that.”

With a bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts and Gender Studies, Claire thinks about her personal experiences, not as a singular experience, but as part of a wider story, much like Tracy Emin, she said. Emin’s work is currently on display at the Yale Center for British Art. Claire’s artistic inspirations also include Marlene Dumas, Miriam Cahn and Tala Madani.

While she used to work with extensions of her own body, she’s expanded into the bodies of older women, including that of her mother and of animals.

She’s also become interested in Korean ghost stories. In particular, the phenomenon of “guijup,” in which people claim to have sexual encounters with ghosts, caught her attention. To Claire, this phenomenon reflects a deeper generational trauma that Korean society has never fully reckoned with, as well as the cultural taboo around talking openly about sex.

Though she remains hesitant to display work in Korea in the future, she’s hopeful that the culture might shift.

KAI CHEN ’26: The history of hair, domesticity and androgyny captured through the lens

Behind the counter of his parent’s Chinese takeout restaurant in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, 5-year-old Kai would nap on stacks of Coca-Cola crates as his parents’ served customers. The restaurant became their home.

Once old enough, they would help with taking orders and handing out food, shuttling between English with customers and Mandarin with his parents.

As a shy kid, customer service didn’t come naturally to Kai, and the performance of customer service led them to bigger questions. In their art, Kai thinks of the performativity of surfaces and the idea of “welding performance as a powerful exertion of power.”

Art was always an insular activity for Kai. Their earliest art education came from surfing Wikipedia and watching YouTube videos. Through this, they discovered Félix Gonzélez-Torres, specifically the piece “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.),” which opened their understanding of what art could be, they said.

Recently, Kai has been interested in domestic scenes and the artifice of photography. Focusing on the distortion of the lens, their most recent project photographs his parents in everyday moments — chopping vegetables, playing Mahjong, even just lying around the house.

The intersectionality of being queer and Asian American is reflected in Kai’s art. Inspired by Agnes Denes gridded drawings, they’ve been thinking about hair as a line, lineage and genetic material, familial connection.

“Hair’s often this racialized, gendered thing, right?” Kai said. “My parents kind of don’t like my long hair but the hair is also part of my queerness.”

In a recent series, Kai focuses on the transcription of a photograph into a drawing or painting, with the grid facilitating this transduction process. Shades of purple are the primary color used in this series, said Kai, as they feel that this color has some proximity to androgyny.

Looking forward, they are excited to spend their summer at the Yale Norfolk School of Art and live in a cottage at the Ellen Battell Stoeckel Estate — which Kai described as an almost “mythical place” with “summer camp vibes.” They look forward to making work outside of classes, as well as the creative freedom that comes with that self-driven process.

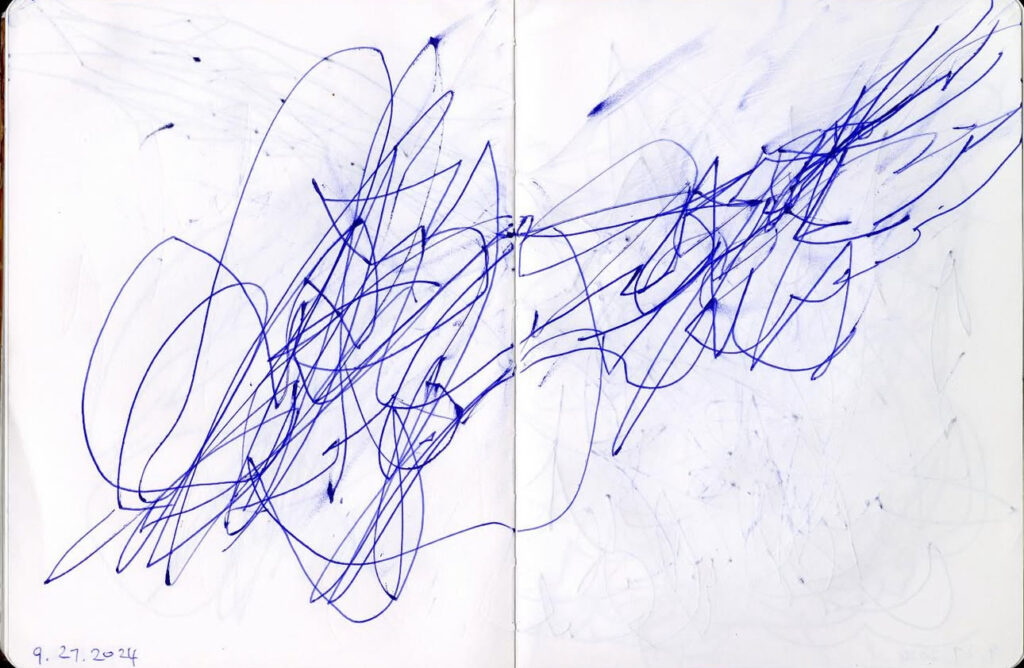

ARIEL KIM ’26: $22 sketchbook and blue ballpoint pen conveys catharsis and immediacy

Ariel Kim ’26 spent part of her childhood in Jinju, South Korea and lived with her grandparents. There, she grew an interest in cicadas, what she described as a “really loud type of insect” abundantly found in Jinju. Her fascination in the sounds of cicadas found its way into her art during her freshman year at Yale.

“I was obsessed with the cicada life cycle,” she said. “They live underground for so long, then emerge for just a few weeks and cry out. There’s something so poetic about that.”

As part of a Creative and Performing Arts exhibit in February 2025, titled “March Blue Period: Life in Ballpoint,” she included a number of pieces with cicada motifs. This exhibit was particularly meaningful for Ariel – as it marked the end of an art block that had lasted for years.

Drawing on the first page of her “overpriced” blue sketchbook from Hull’s, after a long break from drawing, Ariel said, she felt this “this massive sense of catharsis.” Since then, she’s been drawing almost every day.

Her favorite piece from the exhibit, as shown above, came from a place of immediacy and raw emotion.

“If you can see here, the smudges are from my palm, or you see the other side, how it digs into the paper,” Ariel said. “That’s from other sketches I did, pages after pages of it, or just also wanting to escape from that place, truly off the page.”

She plans to travel across Japan and Korea this summer for her creative thesis project — a graphic novel based on an intergenerational story that touches on Japanese occupation and the Korean War. Then, she will return to the U.S. and research more about the Asian American diaspora.

Her dad grew up in Brooklyn and the Bronx, during a time in which few Asian Americans lived there. According to Ariel, she hopes to look at the history of segregation through an Asian American lens and tie these stories together in a part-historical, part-fictional graphic novel.

Alongside her thesis project, Ariel has been planning a fabric arts installation which connects ideas of masculinity and meat consumption together. The project highlights how the subjugation of animals parallels the oppression of women and minorities.

Ariel chose to major in Anthropology, not despite her interest in art, but because of it. To Ariel, a canvas and an empty Google Doc page are similar in multiple ways – both begin completely blank and you begin to fill it with your lived experiences and what you’ve been learning.

PURVAI RAI MFA ’25: Art as a lifestyle

Purvai Rai MFA ’25 spent two years traveling across Punjab, India — following rivers from their source to the India-Pakistan border, studying crop cycles and talking to local farmers about land reform laws.

Growing up in Delhi, the political heart of India, Purvai said that she had a front-row seat to social change. She loved making things — painting, documenting, experimenting — but just creating for creativity’s sake wasn’t enough for her. Purvai was determined to create art with a purpose, work that addresses questions of policy and activism.

Her family is no stranger to witnessing and recording political shifts. Her father worked as a photojournalist, capturing scenes of upheaval and community, while her mother, a conservation architect, taught Purvai how politics and space could intersect, said Purvai.

“From a really young age, I was going to exhibitions, seeing protests, and realizing that art could speak about larger issues,” said Purvai.

This motivated her to spend time working in her ancestral village in Punjab with farmers — learning of their personal interests, struggles and histories.

From her time with them, she learned about the 1976 Urban Land Ceiling Act, a policy intended to equalize property ownership, and its unintended consequences. Some families gained land but others lost jobs, while landlords no longer felt responsible for the entire village’s welfare, said Purvai.

‘It’s not as simple as ‘feudalism was bad and capitalism is good,’” she said. “The social networks within those systems matter. And for many people on the ground, it’s never just about the policy alone.’

Purvai hopes to contain this complexity.

A mixed media artist, Purvai has used locally sourced cotton fabrics to create installations made of textiles, referencing the farmland’s own resources. She’s experimented with rice – red, black, genetically modified varieties – to comment on how climate change, capitalism and tradition all collide in the fields of Punjab. Even the tiles from her family’s ancestral home show up in her work.

Purvai was the 2024 Artist in Residence at the Henry Moore Foundation.

ADITYA DAS ’27: Merging computer science and creative design

Aditya Das ’27 picked up fine art as a hobby over COVID-19 quarantine. Growing up as a STEM student, art became his creative outlet. During his first year at Yale, Aditya enrolled in introductory design class “Art 132” with Professor van Assen on a whim and soon realized that he could combine his love for structure with creativity through the Computing and the Arts major. Now, he’s the co-president of Design at Yale.

According to Aditya, the idea of creating for a specific function — whether it’s a logo, a poster or a promotional piece — feels like blending creativity with problem-solving. Creating art through programming didn’t feel restrictive for Aditya; rather, it added cohesiveness to his work, which he describes as “all over the place.”

In a class project for his introductory design class, he had to design a magazine or brochure advertising a public space. So, he chose to focus on the Bow Tie Criterion Cinemas, which closed in 2023.

He designed a magazine that could fold into a three-dimensional popcorn box. This project was a turning point for Aditya; it helped him realize all that he could do with design.

Aditya reflected on his upbringing as an Indian-American. He said that when he first began studying design in a classroom setting, much of the content was drawn from the Western canon: Swiss modernism, typefaces from European foundries and classic theories about “crystal goblet” design.

Surprised to learn that an Indian type-foundry had produced many of the fonts used day-to-day, Aditya said that he was considering the possibility of Indian design elements in Western work.

Still, he grapples with the nuances of being an Indian American designer, unsure if he can speak authentically on behalf of a culture he only partially represents, said Aditya.

“Because I think when I first started learning design, and here in class, everything I learned was from the West, and everything I did was for the West,” said Aditya. “I didn’t really even know how to incorporate Indian iconography motifs, or design, or like Indian based design into it, because I didn’t really know even what that looked like, or how to draw upon what I’ve seen.”

On Asian-ness in Art

The six artists engage with their Asian-ness in similar and different ways.

Whereas Claire pushes against the restrictions of Korean cultural taboos, Purvai’s art is largely centered around the storied history of her ancestral village in Punjab.

For Aditya, Indian iconography and motifs seem more difficult to claim as ‘his own,’ while Kai’s allusions to the Chinese immigrant experience are based largely on his upbringing, working at his parents’ takeout restaurant.

Similarly, Ariel and Thisbe — two artists who have initially learned art through a Western-centric lens — are teaching themselves new ways of rendering light, shape and shadow as they depict faces and bodies of their community.

The South Asian Youth Initiative displayed “Reclaiming Roots” at the Afro-American Cultural Center from April 2 to April 7, 2025 – an exhibit curated by Nithya Guthikonda ’26.