In 1974, Florence Ludins-Katz and Elias Katz — she an artist, he a psychologist — turned the garage of their Berkeley home into an art studio for adults with developmental disabilities. Across California at that time, people with a range of disabilities were being deinstitutionalized, with little provision made for them after their release. The Katzes viewed art-making as a pathway not only to personal fulfillment for disabled people, but also to their integration into a society that valued their work.

Half a century on, Creative Growth — as the iconoclastic and influential studio in Oakland was named — is celebrating its 50th anniversary with an exhibition, “Creative Growth: The House That Art Built,” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

The exhibition draws from SFMOMA’s half-million-dollar acquisition of more than 100 Creative Growth artworks, the largest purchase by any American museum of the work of disabled artists. The museum acquired 43 more pieces from Creative Growth’s sister organizations in California, also founded by the Katzes: Creativity Explored in San Francisco and NIAD (Nurturing Independence Through Artistic Development) in Richmond.

Time was when such work would have been siloed in collections of “Outsider Art” or folk art. Over the past decade, however, it has been increasingly common to see art by developmentally disabled artists integrated, without contextual fanfare, into group shows or biennials. Cultural institutions, from the Museum of Modern Art to the Brooklyn Museum, have occasionally acquired examples of such work, although it is seldom exhibited except in special displays.

What is happening at SFMOMA is different. The acquisition is part of a partnership with Creative Growth through which the museum, led since 2022 by the director Christopher Bedford, pledges to introduce more art by developmentally disabled people from the three Bay Area organizations into its collection displays, and consequently into the canon of modernist art history.

Tom Eccles, executive director of the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, calls the partnership “unprecedented.” The art historian Amanda Cachia — who writes on disability art — agrees, saying, “The canon as we know it is being reorganized to incorporate the voices of disabled artists who have long been excluded from these narratives. Museums have a long way to go in recognizing contemporary disability art.”

The partnership with SFMOMA, which began in late 2022, is a landmark achievement for Tom di Maria, who joined Creative Growth as its executive director in 1999 and has led the organization to become the most successful and widely recognized studio of its kind in the United States.

The exhibition “Creative Growth: The House That Art Built” opened April 5, showcasing nearly 70 standout works by 11 of the center’s hundreds of current and former artists, alongside a newly commissioned mural in the museum by the acclaimed Creative Growth artist William Scott.

The partnership constitutes the breach of the institution’s high walls that Creative Growth has been striving toward for years. While it may signal a turning point for disability arts, it also comes at a time of change for the organization, as di Maria, 65, looks to retirement and its staff has moved to unionize.

In 2019, di Maria tried to step back from his position as Creative Growth’s leader, first by sharing the position of director, then later moving into a director emeritus role. New appointments did not stay in leadership roles for long. The pandemic complicated matters further, interrupting Creative Growth’s operations. Since December, when the executive director, Ginger Shulick Porcella, left after 12 months, di Maria stepped in once again as interim executive director.

Di Maria tells me that this kind of leadership problem is common in art nonprofits, where long-term directors broadened their job descriptions as their organizations grew. “When they step away,” he said in an interview, “you’re looking for somebody that’s going to be the fund-raiser, the curatorial director, the HR person, the grant-writer, all in one.”

Under di Maria’s leadership, Creative Growth has evolved in ways that make it barely recognizable from the nonprofit he inherited. Its annual budget has risen to $3.4 million from $900,000 in 1999, about a third of which is raised from sales of the artists’ work. (Art sales totaled around $20,000 annually when he joined. When artists sell their work through Creative Growth, the organization takes a 50 percent cut.)

Di Maria has advanced the Katzes’ legacy by pushing to integrate the work made by Creative Growth artists into the mainstream commercial art world. During his tenure, artworks have been acquired by museums including the Pompidou Center in Paris, the Tate in London and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Two Creative Growth artists, Judith Scott and Dan Miller, exhibited in the 2017 Venice Biennale. Many others have had solo shows at respected commercial galleries across the world.

The sale of artworks by disabled people, di Maria says, is a means of “getting a seat at the table.” Collectors acquire often-inexpensive works, and become invested in the lives of the makers; dealers take notice, and put on shows; prices go up; museum boards promote the work they own to curators; work gets donated to museum collections. Once the art is inside the museum, the real work can begin: changing the way the public values and understands the lives of disabled artists.

On one level, the exhibition — organized by the SFMOMA curators Jenny Gheith and Nancy Lee — presents a social history of disability arts in the Bay Area and the Katzes’ groundbreaking initiatives. This story is told through a well-designed interpretive display in a new gallery called “Art in Your Life,” and in cases of ephemera such as fund-raising letters and event announcements that frame the exhibition in documentary terms.

On another level, however, it is a show of art as accomplished as any in the museum. The first gallery showcases work by three of Creative Growth’s pre-eminent figures, and one emerging talent. Dwight Mackintosh, who died in 1999, was one of the first artists from the organization to win international attention for his drawings. Using felt-tip and colored paint, in his looping hand, he drew groups of translucent figures often surrounded by a distinctive, intermittently legible script.

Mackintosh’s repetitive mark-making rhymes with the intensely overlaid words and shapes in drawings and paintings of Dan Miller, 62, and in an assemblage sculpture by Judith Scott, who died in 2005: a small chair wrapped with strips of fabric and twine, tying in other items including a basket and a bicycle wheel. Meanings are buried deeply in these works.

Do not confuse such practices with art therapy. Just like professional artists who work and rework a set of ideas and motifs, Mackintosh, Miller and Scott spent decades honing private languages, resulting in oeuvres that embody their powerful personal visions.

In that first gallery is also an arresting video by Susan Janow, 43, her first foray into the medium. In “Questions?” (2018), Janow stares into the camera, tight-lipped, while questions are asked of her (in a voice-over, also recorded by Janow), ranging from the banal — “Do you wear a watch?” — to the existential — “Do you trust others easily?” “Who do you miss?” “Where do you see yourself in 10 years?” Her art reveals that her interior life is shaped as much by inquiry as by confident conclusion.

Another highlight of the exhibition is a vivacious untitled abstract painting, from 2021, by the Berkeley-based Joseph Alef, 43. In an exhibition text, Alef explains that nonfigurative work makes it “easier to get all of the emotions out.” These texts admirably elucidate artists’ processes and approaches without disclosing the nature of their disabilities, which might risk skewing viewers’ interpretation of their art.

If some artists choose to share details of their lives through their art, that is their prerogative. Camille Holvoet, 71, who worked at Creative Growth until 2021, makes cheerfully frank, brightly colored drawings of her joys, anxieties and hopes. Created between 1987 and 1998, the pictures on view depict her medications, her fear of public transport, her experience of moving to a new group home, and — poignantly, in this context — a picture of a smiling woman next to stacks of cash and checks: “Making More as Mush Money as a Good Artist, Without No SSI Cuts and No Pay Tax.”

Ordinarily, I am not inclined toward such illustrative artwork. But Holvoet’s pictures achieve one of the most profound aims of the exhibition, and indeed of Creative Growth’s founders: to help disabled artists thrive as individuals with agency and potential. Whether an artist is using creative work to narrate their life story or to transcend their circumstances, making art is a deeply assertive act.

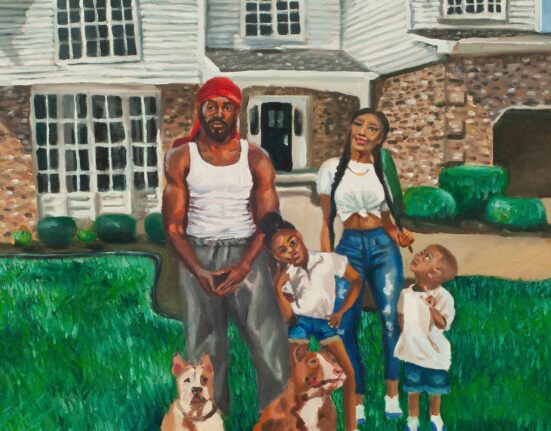

Exemplary is William Scott’s commissioned mural “Praise Frisco: Peace and Love in the City,” part of the museum’s “Bay Area Walls” series. Over the course of his artistic career, Scott, 59, has painted his vision of a utopian San Francisco of the future, a city he calls “Praise Frisco” which incorporates rejuvenated elements of his past. In his mural at SFMOMA, we see smiling, youthful versions of himself and his mother, alongside a spotless depiction of the Alice Griffith public housing development where he grew up. (Also present are green flying saucers, labeled “Wholesome Skyline Friendly Organizations.”)

Three days before this triumphant exhibition opened, di Maria received a letter from Creative Growth staff members announcing their intention to unionize. “Forming a union will help ensure more equitable hiring and pay practices, standardized benefits, greater protections, safer working conditions, and improved procedures around transparency and accountability,” it read.

Di Maria accepted unionization soon after, on April 11. In recent years, staff members at arts institutions across the country from museums to art schools have been unionizing. Sam Lefebvre, a part-time artist aide and member of the union Creative Growth United, told me that high turnover, owing to unsustainable working conditions, can negatively affect the artists, who may form close bonds with studio facilitators, and who often respond best to routine and stability.

At this moment of transition for both Creative Growth and SFMOMA, all eyes are on the future. Museums across the country are working to connect more deeply with their audiences, and by including and celebrating the work of disabled artists in their collections, they will better reflect the lives and experiences of all their visitors.

“One in four people in the United States identifies with disability,” the scholar Jessica Cooley, who writes on disability arts and museum studies, said in an interview. “Disability art and artists are already everywhere, in every collection, making incredible impacts on the art world.” SFMOMA’s partnership with Creative Growth can be seen just as an acknowledgment of the contributions disabled artists have made to art history.