Slavery has been a prominent theme in contemporary US and British art for many years, but French institutions have been slower to foreground the issue. Now the Panthéon monument in Paris has given carte blanche to artist Raphaël Barontini to bring lesser-known figures of emancipation into the light.

Issued on:

5 min

Freedom fighters have been at the core of Raphaël Barontini’s work for many years. But to have his pieces displayed in the Panthéon, a hallowed space reserved for France’s national heroes, is deeply meaningful.

Barontini is acutely aware that his exhibition “We Could be Heroes” is not only an opportunity to pay tribute to lesser-known figures involved in the fight against slavery, but also a historic step forward in terms of publicly addressing these themes.

The Panthéon, whose dome looms over the capital’s fifth district, is where France’s great intellectuals and statespeople are buried – notably Victor Hugo, Voltaire, Marie Curie and Jean Moulin.

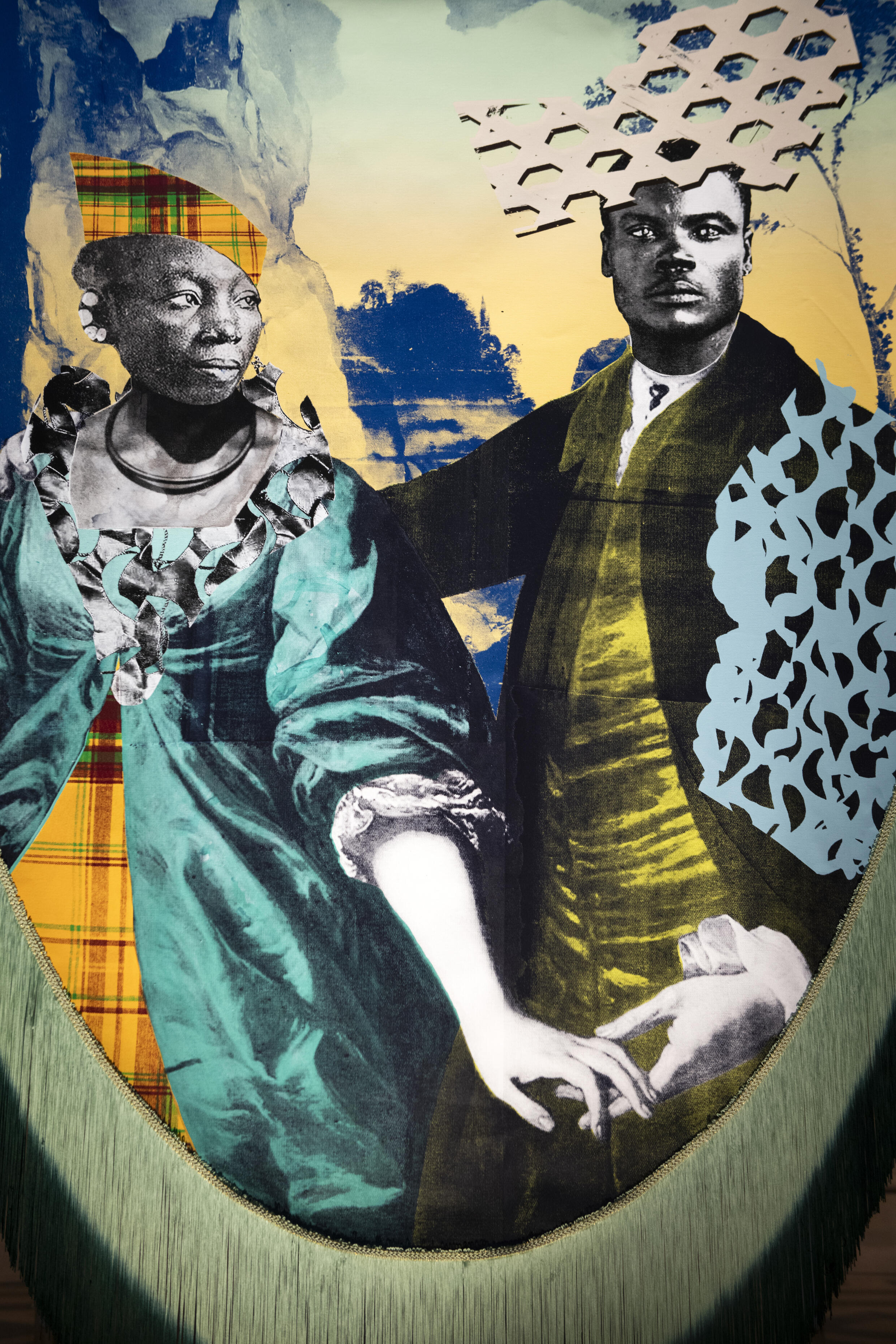

Suspended under its monumental ceilings, Barontini’s giant silkscreen-printed banners flutter gently, inviting visitors to look up.

The pastel colours and graphic motifs evoke scenes from France’s history of slavery – the trans-Atlantic crossing, sugar plantations, battles for freedom.

Nearby, contrasting with the heavy stone statues and massive columns, colourful shield-shaped flags stand in a line.

Upon them are the faces of men and women who marked the long fight for freedom with their bravery and acts of resistance: Anchaing and Héva from Réunion Island, Louis Delgrès from Martinique and Guadeloupe, and Sanité Bélair from Haiti, among others.

When he began exploring slavery and its eventual abolition as an arts student nearly 15 years ago, Barontini admits he was in uncharted waters. At the time, few other contemporary artists in France had dared to take on such an explosive subject.

“A certain part of the art world wasn’t ready to accept it” and nor was the general public, he told RFI.

After graduating, Barontini accepted residencies abroad and his work gained traction, especially in the United States where “these subjects are studied and talked about”, he says.

Rebalancing national history

Barontini grew up in the socially and racially mixed working-class suburb of Saint-Denis, just north of Paris – a stone’s throw away from the famous Saint-Denis Basilica where French kings are buried.

His curiosity about his own heritage, linked to Italy through his father and Guadeloupe through his mother, began at a young age.

As he travelled back and forth as a child to visit relatives in Guadeloupe, he became intrigued about how these tiny Caribbean islands fitted into the great saga of French history.

The discovery of his country’s violent participation in hundreds of years of slavery signalled an artistic awakening.

It brought him an opportunity to unearth stories of courage and determination, and focus on the accounts not published in school history books or represented in museums. Out of ugliness, he created beauty, rehabilitating lost memories.

“Many people have thanked me for my work,” Barontini told RFI.

“I see that as support for what I do, but I think it also shows there’s a need to talk about history in all its complexity and all its forms. I’m trying to rebalance our national history by using art.”

A powerful drumbeat

To accompany his visuals at the Panthéon, Barontini chose to incorporate an original sound piece composed by American artist and music producer Mike Ladd. The mysterious electronic sounds are a contrast to the hush that usually reigns in the monument.

Barontini also organised for 40 musicians from the Caribbean carnival group Choukaj to perform in both the opening and closing weeks of the exhibition, which ran from 19 October 2023 to 11 February 2024.

A large crowd turned out for the finale in early February. Young and old alike, they kept time with the feverish beat of drums, hypnotic horns and chants that filled the cavernous space, bringing history to life.

Barontini says he’s proud and humbled that his works have found their way into one of France’s most symbolic monuments, even temporarily.

“I am happy to have had this carte blanche today. It proves that despite everything we’re making progress. It was important for me to see these figures included in the Panthéon, even for a temporary exhibition.”

He says he’s preparing more shows for elsewhere in France and abroad, hopefully one day in the Caribbean.

Barontini refers to the Panthéon performance as a “funeral march”, a commemoration of one of the darkest, deadliest chapters of French history.

But by centring those who fought for the humanity of themselves and others, it becomes one marked with joy and pride – creating echoes that will continue to vibrate in the austere space and beyond.

Celebrating black history in France

While Black History Month is celebrated across the United States in February and in October in the UK, France does not have an official equivalent.

However, groups like Memoires et Partages (“Memory and Sharing”) are trying to rectify that by holding their own unofficial celebrations. The organisation is hosting a series of events in February to highlight the role the French cities of Bordeaux, Nantes and La Rochelle played in the slave trade until it was finally abolished for good in 1848.