We Were Lost in Our Country, an exhibition of contemporary Indigenous Australian painting currently on display at the Nevada Museum of Art, is anchored by a film of the same title, projected on loop and situated roughly in the middle of the collection of paintings. That film, by Vietnamese artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen, documents the creation of the “Ngurrara Canvas II” (1997), a painting roughly 260 by 30 feet across. It serves as a vibrant map of Aboriginal territory inhabited by four language groups. Forty-four artists worked on it collectively, standing, sitting and walking across the canvas, over a period of two weeks. The painting is a work of both memory and cartography.

A still from Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s 2019 film We Were Lost in Our Country.

The canvas was also used as part of the legal process to reclaim Aboriginal rights to land that Australia seized from Indigenous groups under the colonial fiction that the continent was “terra nullius,” land belonging to no-one. Since 1992, Australia has recognized what is called “native title”—land rights based on a group’s maintenance of traditional laws and customs.

When the painting was presented to the National Native Title Tribunal, it was essentially a map of displacement. By the end of a 10-year negotiation with the government, the map described the territory that was returned to Indigenous control.

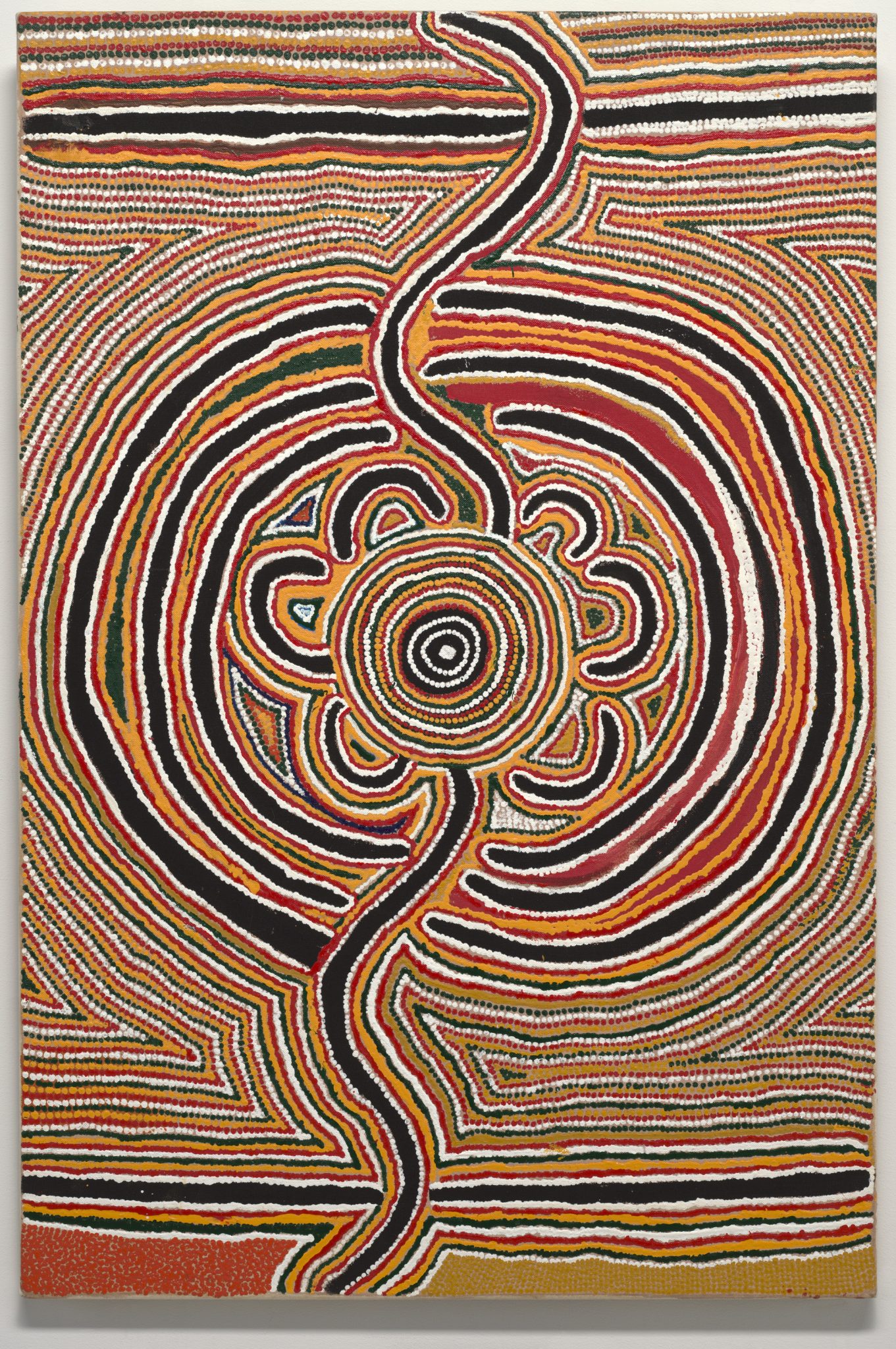

Some of the paintings that flank the film projection were created by artists who worked on the “Ngurrara Canvas II,” and others are from different communities, also in and around the Great Sandy Desert, working at Art Centers such as Balgo, Warmun, Bidyadanga, and Kununurra, that help support and sustain Aboriginal artists. Taken together, the paintings create an atmosphere of profound vividness and vitality. Some of them do function—like the “Ngurrara Canvas II”—as maps, describing relationships between water holes and navigational landmarks. Color fields, curved lines, and recurring shapes form organic, visually harmonious constellations—and they dispel, with their graphic density, the fiction of the desert as “empty space.” Many of the paintings use the technique of “dot painting,” a technique akin to pointillism, where outlines, shapes or color fields are produced by small dots of paint applied to the canvas. When seen up close, when the constituent dots can be made out, it feels like you’re observing the painting at a cellular or atomic level, and the colors take on a vibratory hum.

The paintings can be appreciated for their formal exuberance, but they’re much more than formal exercises—they are expressions of an ancestral relationship to the land, and the spiritual and cultural dimensions of being connected to a place. The exhibition does an excellent job of situating the work in a broad context.

I had the opportunity to talk to Apsara DiQuinzio, senior curator of contemporary art at the Nevada Museum of Art and curator of this show. The following interview has been edited lightly for clarity and flow.

Queenie McKenzie Nakarra’s 1997 painting “Mary and Joseph” is part of the exhibition.

The “Ngurrara Canvas II” can be framed as decolonial art. But it’s not just engaging in aesthetics or symbolism—it functioned as a tangible decolonial act. It seems to exist in the world of aesthetics, while also existing as a legal document, in some sense.

Yes, it’s a living document, it’s a legal document, it’s an incredible work of art. I would consider it to be a masterpiece. And it also points to a new direction for how a painting can be used and thought about, which is one of the things that really attracts me to this work.

The motifs and the subjects that they are painting are, for the most part, their links to their country, having been displaced—in some cases violently. They aren’t able to visit all of the areas that they used to visit when they were young, so they have a memory of these places that then gets recorded in the paintings. It is also a vital tool for passing along this important knowledge to younger generations. So, painting becomes a powerful tool for the transference of community and cultural knowledge.

Do you have a sense if the artists made modifications, in their approach, for their audience? The painting was created to petition for Native Title to the land, so a crucial part of their audience was the Australian government.

I can’t speak on behalf of the artists, but when they started to make it, it was Jimmy Pike who laid down the first line on the canvas. That line represented the Canning Stock Route, which radically divided the area in Western Australia. It’s a series of wells that stretch over a thousand miles in the desert created by the cattle stations. [In U.S. English, that’s “ranches.”]

That affected the land. It’s through that line that Jimmy Pike made, that everyone was able to figure out—OK, this is my land over here, this is my land over there. Everyone went to their area pretty quickly after that line had been determined. They refer to themselves as “jila people.” “Jila” means “living water.” They are the protectors of the jila, the sacred water holes in their area. And so this is a painting that proves to the government that they know where all of those jila holes are and that they have cared for and maintained them. That information has been passed down to each new generation, stretching back 40,000 years.

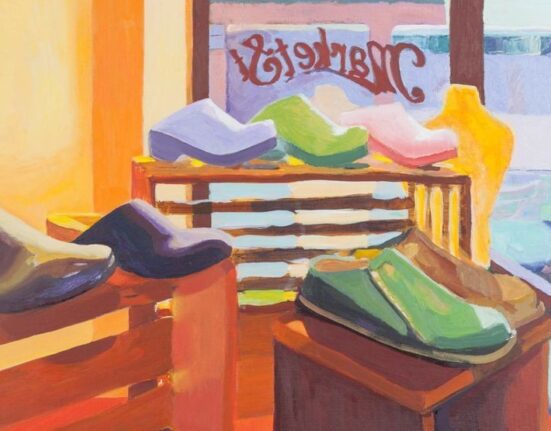

Christine Yukenbarri’s 2005 painting, “Winpurpula,” is part of the exhibition.

I’m curious how you would position this work in relation to abstraction, in the Western fine art context. These paintings appear to participate in abstraction, but it seems motivated very differently.

Yes, I definitely think that you can appreciate it within a more Western context. Paintings by Indigenous Australians have been much more marginalized in terms of the context of the contemporary art world than others. But I do think that you can appreciate the paintings within the context that we know. There are a lot of similarities—pointillism, optical patterning, expression, gesture—which you might think of in relation to abstract expressionist painting. You also have to remind yourself that they probably weren’t, at a certain point, looking at people like Jackson Pollock—that just wasn’t really a reference point for them.

It could perhaps be seen as a sort of “parallel evolution.”

They work on the ground and on tables for the most part.

That’s very Pollock.

Yes, but they also stand on it, and sit on it. It’s not a precious object in terms of a commodity – although it is a special, precious object in a different sense and the paintings can be quite valuable economically. When they made the “Ngurrara Canvas II,” they were all sitting on it together, painting their country.

They say in the film: this is a beautiful work of art. And it is also who we are. This is our culture. This is our law. These paintings are us.

They have their own unique iconography. The smaller, U-shaped forms that you see in the paintings represent people. The larger ones—those are mounds that can be sandhills, or windbreaks. They also shape and form those around the jila. In our Western context, I compare them to earthworks, because they’re actually making these forms around the water holes—shaping them after the shape of the clouds that bring the rain. They are part of ceremonial rituals to bring rain, and to honor the water.

Rosie Nanyumi’s 1995 painting “Kumbuljiri, near Mangkai in Great Sandy Desert,” is part of the exhibition.

I don’t know if I’m viewing them correctly, but one thing that appears to connect the paintings to Western mapping practices is an aerial viewpoint. They aren’t limited to an aerial view—other perspectives seem to be interpolated into it. But the paintings do look like they participate in that perspective “from above.”

Once you see aerial of footage of Australia and the landscape, it all comes alive in a different way. You see all the spinifex plants, and then all of a sudden the dots make sense—the spinifex plants have these white seeds that are used for food, and they gather the seeds. A lot of the paintings are covered in white dots that represent spinifex seeds. The symbolic language that they’re using in their paintings is intricately tied to the landscape.

The fact that it is an aerial perspective, I think, is pretty remarkable because they weren’t flying planes. But through their knowledge of it, they had a kind of god’s-eye view of their land—which is, I think, really key.

I have a question about the communitarian aspect to the work. The “Ngurrara Canvas II” had over 40 artists working on it—and even some of the smaller canvases you have on display were made collaboratively, by multiple painters. The “art center model” that many of these artists are involved with, seems very community-oriented. It’s distinct from the Western fine art picture of the “individual genius.”

There’s a lot of community, and sharing stories and traditions in the art centers—it is a really community-driven practice. And it’s also a job. They are making a living by doing this. It’s among the more viable options, especially in the very remote communities, where they’re living on their homelands and anchored to a specific community center or art center. They’re able to sell their work and earn a living while also maintaining their knowledge, and sharing their knowledge among younger generations.

It’s a stark contrast to the idea of the isolated artist in his studio working alone and trying to figure out this new innovative mark or style. The personality and the individuality comes through in the paintings in a unique expression, but it’s not the drive, in the way it was for a lot of modern Western artists.

Though the work comes from Australia, it seems very locally relevant. For example, the way that prescribed burns are a part of our wildfire management, which is connected to Indigenous land stewardship practices that predated European settlement. Or the way the Washoe tribe had to provide evidence of the continuity of their shamanistic relationship to Cave Rock, when they were trying to prevent climbing on that sacred site. I don’t want to “flatten” indigenous cultures that are very distinct, but I see some common threads.

Right—and that primary thread is, I think, an honoring and a reverence and a sense of belonging to the land and environment that you live in. That is so important to acknowledge if we—for Westerners—want to reorient our thinking. We have to start thinking that way in order to fix the environmental problem that we created, which has been fueled by colonialism and industrialization. Indigenous ecological wisdoms in that sense are really important models and guides for us going forward. We have to think more about that, and privilege it and listen to it and learn from it.

We Were Lost in Our Country is on view at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno through March 23, 2025. Related events include a screening of the film Putuparri and the Rainmakers at 6 p.m. on Aug. 22.

On Nov. 1, Dr. Debra Harry, Associate Professor in Indigenous Studies for the Department of Gender, Race and Identity at UNR, will give an Art Bite talk at noon.

Photos courtesy Nevada Museum of Art.