Kyiv was supposed to fall in three days. That’s what talking heads and pundits in media were saying, rather dismissively, before the February 2022 Russian invasion on Ukraine. They suggested the fight would be swift and decisive but instead the Ukrainian resistance persisted. Never mind, three days. The war is now pushing towards three years.

“What is this nation?” asks David Gutnik, a Brooklyn-born film-maker of Ukrainian descent. “What is this people? What is this identity?”

He’s posing rhetorical questions prompted by the war and describing the surprise when a country and its people, who were so quickly dismissed, held its ground. If the world believed that Ukraine would fall so soon, it’s probably because they had no idea who the Ukrainian people are. Gutnik’s profoundly resonant documentary, Rule of Two Walls, is here to remedy that.

The film is about Ukrainians on the frontlines; not the soldiers, mind you, but the artists who are standing firm on their homeland against the ash and rubble. They are painters and singers, hosting exhibits and shows, despite the constant gunfire and shelling that inevitably becomes part of the art. They’re fighting to create and protect culture, and by extension their Ukrainian identity, as a response to Vladimir Putin’s repeated insistence that they have none.

“This is a war of shells and missiles and drones,” says Gutnik, on a Zoom call from his home in New York. “But it is also a war of identity, a war of memory, a war of who gets to write the history. Does the colonizer get to write it or do the people who want state and nationhood and dignity get to write it?”

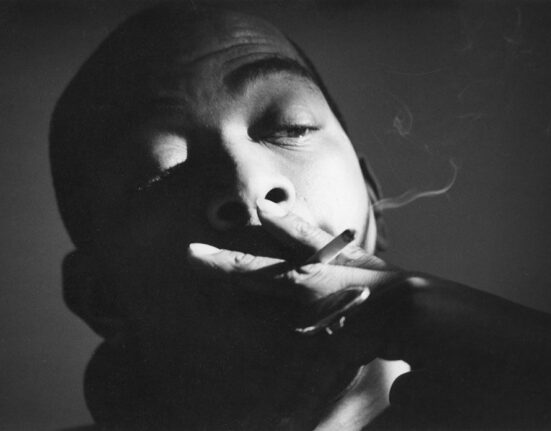

Among the collective resistance of artists in Rule of Two Walls is Bogdana Davydiuk, whose haunting Dada-esque street murals and mosaics reflect the fiery passion and disorientation of war; rapper Stepan Burban, aka Palindrom, who spits angry rhymes in the face of Russian aggression; and Kinder Album, an anonymous artist whose child-like drawings feature naked bodies appearing deeply vulnerable before the inhumanity of war. Speaking off-camera, it’s the anonymous artist who recites the film’s title. The “rule of two walls”, she says, means to find a corridor when there isn’t enough time to reach shelter before a bombardment.

The film-makers themselves – including Gutnik, his cinematographer, producer, composer and sound recordist, who all appear on-camera – become part of this resistance. They too are artists, after all. They’re making a film that experiments with disembodied voices and other destabilizing techniques to capture, as best as cinema can, the experience of being displaced by war. Rule of Two Walls achieves a certain haunting poetry as it becomes an extension of its subject, and allows the film-makers space to share what they’re witnessing and how they process the trauma of it.

Gutnik initially set out to make a film about Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war; one that would be reflective of his own broken connection to his homeland. His family fled the area not long before he was born. They were part of a diaspora that could barely speak Ukrainian, since so much of the language and culture was suppressed when the country was part of the USSR, but who now feel a desire to reclaim their heritage, especially in response to the war.

“All these Ukrainians in diaspora have been kind of living quietly in a hornet’s nest that’s been still,” says Gutnik. “And this war has shaken it. Now all these bees are buzzing all over the world saying ‘Wait, no! I am Ukrainian! I’m here! They can’t tell us who we are.’”

Gutnik changed directing when finding an appealing anchor to his film in Lyana Mytsko. She’s the director of Lviv Municipal Art Center, which has been serving as a shelter during the war but also a space to create and process. He reads a quote from Mytsko that caught his eye. She says that artists can’t take up arms but each one is “a gun of Ukrainian culture”.

When in 2022, Gutnik got in touch with Mytsko, she was peeling away at the old Soviet walls in the arts centre space, discovering pre-USSR murals intentionally buried behind. That act, says Gutnik, captured what he then knew his movie should focus on: “reclaiming our cultural identity and history, this sort of decolonization of ourselves and consciousness”.

Throughout Rule of Two Walls, Gutnik shows the creation and preservation of art, but also the war waged against it. Theatres and museums are bombed as a strategic erasure of history and culture familiar to any group that has in the past or is currently facing genocide.

Indigenous cultures have their language and ceremony taken from them. Nazis burned books and pillaged Jewish art. The Sri Lankan army set the Jaffna library ablaze during an early phase of that countries eventual genocide against Tamils. On top of the tens of thousands mostly women and children killed in Gaza over the past 10 months, Unesco has verified at least 50 cultural sites including mosques and museums that have been damaged – though reports from January put that figure at least four times higher.

“When somebody wants to commit genocide, they say [these people] don’t exist,” says Gutnik, citing historian Timothy Snyder while explaining the underlying goal behind targeting culture. “So when they destroy those people, it’s not really genocide because they never existed in the first place.”

Gutnik continues: “Two days before the full-scale war, Putin based his entire rationale for the invasion of Ukraine, on this notion that Ukraine doesn’t exist. The cultural space is a front line in this war. That misinformation, those misunderstandings about Ukrainian history are weaponized, and then that weaponization of history turns into a genocide, turns into people dying.”

Gutnik’s film doesn’t hold back when facing that horror. The images of charred and mutilated bodies that the people in his film face constantly are on display. He’s heard some audiences expressing discomfort with seeing that. Though to not show it, Gutnik suggests, would be betraying the reality and subjectivity of the people in his film, whose families and communities are the ones dying.

Gutnik also noticed that it’s American audiences untouched by war, rather than Ukrainians, who questioned his decision to show the very graphic horror. “If you don’t have to see it, you can tune it out,” he says, explaining an option Americans have that Ukrainians don’t.

I suggest there’s a connection between those who don’t want to see the horror and those won’t acknowledge a genocide as it happens, whether in Ukraine or Gaza.

“If you don’t name it, you don’t say it, you don’t show it, then you don’t have to deal with it,” says Gutnik, before citing Snyder again.

“Whenever anyone says the word ‘genocide’ there’s somebody in the room who’s doing an eye roll,” he says. “The reason that we don’t like to call something genocide, the reason we do that psychologically with our eyes is because if we admit that it’s happening, we’re admitting complicity.

“We’re admitting that it’s happening on our watch. So we don’t want to call it that.”