NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE

{I}

haven’t been to the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, for a couple of years. It’s one of a dozen or so museums dedicated exclusively to American art, so, having been a curator of American art and the director of the Addison Gallery, I’ve always viewed the place with great fondness. The collection, initially heavy on the cowboy art owned by Amon Carter, who also owned Fort Worth’s premier newspaper, evolved to become superb and encyclopedic.

I adore the place, as I did Ruth Stevenson, Carter’s daughter, who chaired the museum board and piloted and financed its ascent. Last week, I wrote about Kay Fortson, who chaired the Kimbell board and was, over nearly 50 years, the mastermind of its development into a national treasure. I’ve met Fortson but knew Ruth Stevenson well, both as an art potentate and a good donor to one of my museums.

Stevenson (1923–2013) established the Amon Carter in 1961 as her father’s will dictated. She knew very little about art but soon wanted, in the days before the Kimbell, to give Fort Worth a distinguished museum that went beyond his paintings, sculptures by Remington, cowboy art by Charles Russell, and horse pictures. The pianist Van Cliburn, also from Fort Worth, was a prodigy, superstar, and cultural hero by the late ’50s, giving Fort Worth a taste of cultural celebrity. Local leaders saw it as a matter of civic pride to yearn for more and to go git it, with Texas-size resolve. Leaving Dallas in the art dust was a delicious obbligato.

Stevenson went out and acquired. Now, with crème-de-la-crème works by Eakins, Bierstadt, Cole, Hassam, Demuth, Stuart Davis, O’Keeffe, and, of course, Remington and Charles Russell, and many other things, her vision is a wonderful reality. What I remember and admire most about her was her deep, self-taught curatorial and art-history knowledge. She was a self-made connoisseur and an instinctive one. She knew everything acquired for the collection, and not only because she blessed it. She made it her business to understand it.

And Stevenson took pride in bringing the best to Fort Worth, which, smaller than Dallas, has better art. This isn’t to say that the Meadows Museum at SMU in Dallas isn’t exquisite, or that the Dallas Museum of Art is small beer. Fort Worth wins the Blue Ribbon in the Longhorn and Aberdeen Angus categories but also for its Sargent and Bierstadt at the Amon Carter and its Picasso and Caravaggio at the Kimbell. And I haven’t mentioned its nice contemporary art museum, the Cowgirl Hall of Fame, or the Sid Richardson Museum. Or its superstar museum buildings.

My last visit to the Amon Carter, alas, was to review Mythmakers: Homer and Remington, its ambitious, rich-in-art but intrinsically defective exhibition comparing Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington. Manet/Degas, the Met show I reviewed a couple of weeks ago, succeeded in the “compare and contrast” genre where so many other efforts like it have failed, as did Homer/Remington. Manet and Degas can go tête-à-tête without one or the other getting clobbered. Homer is a great artist. Remington isn’t. Putting that inconvenient reality aside, they have very little to do with each other.

Mythmakers wasn’t bad. The art was too good. The Amon Carter plays on the national stage and got the best loans. Still, the exhibition’s weak-tea colonialism and imperialism themes were, to be diplomatic, uninspiring. A community-voices component was dull. There, members of the “community” gave their own anodyne views on the art. Since the subject was Remington, one of the commenters had to be Native American, who, on cue, did the “they stole our land” shtick.

On that visit, I also saw the Mitch Epstein: Property Rights exhibition, which displayed mammoth photographs by Epstein promising to “challenge our perspectives” on citizenship, environmental degradation, and property rights, using views of Texas and Arizona. Again, it was predictable as well as insipid. In one photo, an old lady looks beseechingly through a gridded border wall in Arizona, carrying her handbag and wearing a tidy cardigan sweater, as if the current invasion of illegals comes dressed for tea and crumpets. Another depicts a flag flying upside down, another a young man hugging a tree. Epstein’s a good photographer, but the exhibition displayed calendar art for bobos.

Booorrring, this show was. If anything’s degraded, it’s the Amon Carter’s curatorial philosophy. Is the Amon Carter going soft-core woke? Is it addicted to that new drug I call idiotica? This would make for pious preening, finger-wagging, and tut-tutting over race, gender, and settler colonialism, the latest fashion in piety.

I was happy to be surprised. Two of the exhibitions now on view are great, each in its own way.

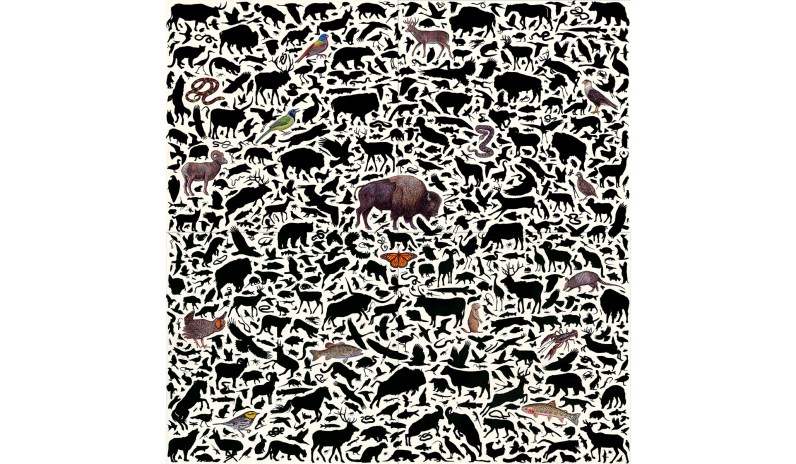

Trespassers: James Prosek and the Texas Prairie chronicles Prosek’s look at Texas’s grasslands in the face of population growth, farming, invasive species, and changes in the climate. Prosek (b. 1975), a writer, artist, and naturalist, became famous as an undergraduate at Yale for his book Trout: An Illustrated History, which used his elegant watercolors and original research to explore the evolution of this crafty creature. Prosek is our 21st-century Audubon of fish but also of wildflowers and birds. He merges good scientific inquiry with both the empathy and the emotion of the Romantic era. Boy, we can use more Romanticism today.

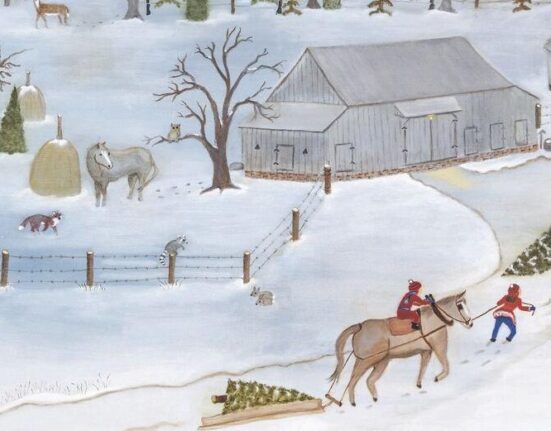

Prosek isn’t a propagandist. He’s not into cant or jargon. He’s the furthest thing from swivel-eyed wackos who live and breathe grievance and resentment. Off and on over the past two years, as an artist in residence at the Amon Carter, he visited grasslands throughout Texas. Wild grasslands are unplowed prairie with widely spaced trees. They’re home to hundreds of native plants. During his residency, Prosek made paintings, watercolors, and sculptures depicting the character of Texas prairies, what threatens them, and how nature crosses — or trespasses — over forces that thwart them.

Sotol leaf, yucca flower, antelope horns milkweed, and rattlesnake master are new to me. They’re spindly, reticent things. Dry weather and hot sun don’t make for flamboyance. Prairies grow plain but pretty plants, often with dab-size flowers that look like broaches. About a dozen watercolors of these and other plants fill one long wall of the exhibit. Big wall murals depict hundreds of mammals, amphibians, and reptiles that depend in some way on grasslands.

For thousands of years, fire, mostly from lightning, was a prairie’s friend. Now we humans don’t know what to do with fire, which targets built environments. Prosek learned during his travels through Texas that some prairie plants there once also grew in rural Connecticut, where he lives. Tribes there wanted grazing land, too, and used controlled burns to keep trees at bay and grasslands in good shape.

Prosek is a good teacher who thrives on the soft sell, asking questions and suggesting that visitors be aware. It’s hard to do a show that’s beautiful, erudite, and sensual, but he and the museum have pulled it off.

I visited the museum to see Trespassers and the Amon Carter’s sublime permanent collection but didn’t know about The World Outside: Louise Nevelson at Midcentury, an exhibition of about 50 works by Nevelson. I look at Nevelson (1899–1988) primarily as a Maine artist, though she was born in Russia, came to Maine as a girl with her family, spoke Yiddish at home, and, after the 1920s, lived and worked in New York.

A Maine artist? Her medium is wood, and wood’s the ubiquitous material in Maine. Her father worked in Rockland in Maine first as a lumberjack and then owned a lumber mill. Her work has the hacked, rough look of Winslow Homer’s late seascapes, painted in Prouts Neck, Maine, or of Marsden Hartley’s views of Maine, or of Bernard Langlais’s Abstract Expressionist wood sculptures from the 1960s, now on display in an outdoor sculpture preserve in Cushing, Maine.

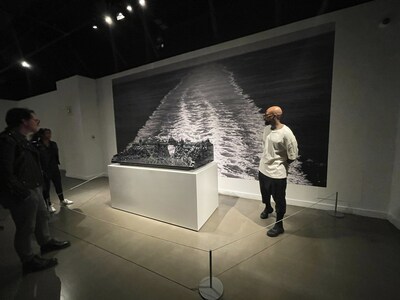

The World Outside looks beyond Maine. Nevelson, coming from Maine, was better equipped to see American folk art as an aesthetic guide for modernists for its simple geometry. I didn’t realize how inspired she was by Mayan architecture or how well she translated her sculpture style to prints. She was a brilliant lithographer who slapped textiles on her lithographic stone to make textured prints. The Amon Carter owns her lithographs from the ’60s as well as Lunar Landscape, her black sculpture, from 1959–60, made of scavenged materials including a bedpost, a juggling pin, and part of a chair. These anchor objects launched the exhibition, which goes next to the Colby College Museum of Art in Maine.

The all-women curatorial team behind The World Outside makes too much of repressive gender roles and obsessions with domesticity that Nevelson rose above. She probably would’ve hated the academic environment in which the curators place her. She thought of herself as sui generis and didn’t believe in group identity for anyone. “I’m not a feminist,” she declared, saying she had liberated herself from all stereotypes. In the ’60s and ’70s, Nevelson was, with Hopper, Warhol, and probably Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein, a living American artist that nearly every sensate person in the country knew. She was by then a star among critics, connoisseurs, and collectors, too.

Nevelson has had plenty of exhibitions, but it’s always good to give her another look. Like all of the Amon Carter’s shows, it’s intuitively arranged in spaces suiting the work and the artist’s personality — big and bold, in this case. I loved it.

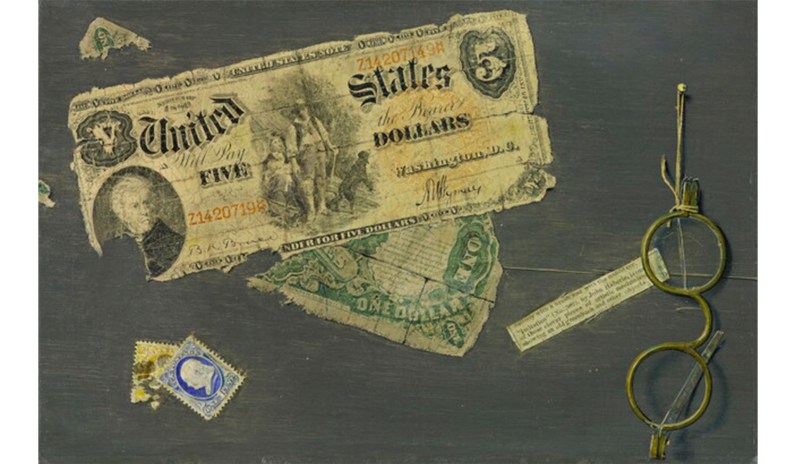

I’ve been to the museum so many times that I’ve found favorites I consider family. That’s rare in a museum so far from home, but the Amon Carter’s collection is that good, and the place is comfortable and serene. Arthur Dove’s Thunder Shower, from 1940, conveys the look and sound of a squall in orange, red, and blue overlapping sawtooth shapes. Can You Break a Five is a tiny “fool the eye” painting from 1888 by John Haberle. He’s cryptic and ironic as well as a prophet of Pop Art. Mother’s Darling (Bo-Peep), from 1872, might have been kitsch except that Eastman Johnson painted it. It shows a mother and baby playing peekaboo in a dark Victorian cocoon with just enough red to feel warm, cozy, and full of love and possibility.

Dove’s plaster, wire-mesh, cloth, and cork collage, done in 1925, must have been a stretch for Stevenson when the Amon Carter bought it in 1966. It’s displayed in a gallery near the Prosek exhibition. It’s as rough and spartan as a piece of Texas, and Stevenson wasn’t afraid to be daring. It’s next to a gray, turbulent John Marin seascape painted in Mane in 1933. The Amon Carter owns lots of New England seascapes. This isn’t odd. Fort Worth, the gateway to the West, might like to dream about brisk sea wind and bracing salt air. New England and the Hudson River are the raw material for much of American art, so the Amon Carter’s watery acquisitions make sense.

These pictures are small things that I love seeing and cherish. I always look at Swimming, from 1885, by Eakins, and Thunder Storm on Narragansett Bay, from 1868, by Martin Johnson Heade. They’re big-kahuna paintings and the epic acquisitions of their time.

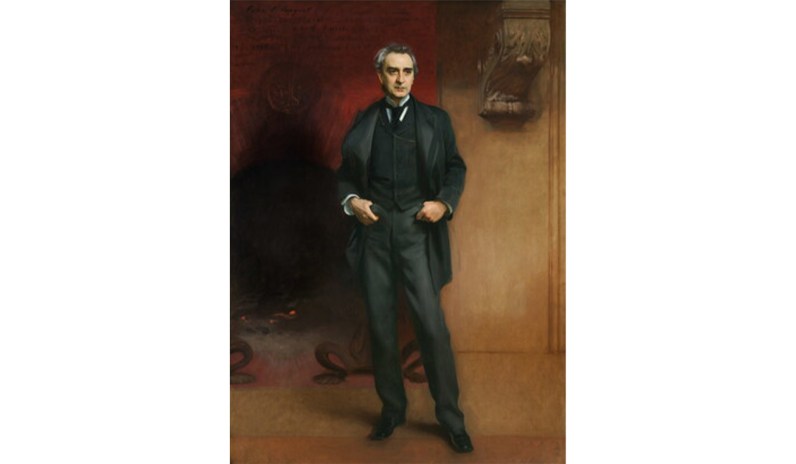

And then there’s John Singer Sargent’s swagger portrait of the actor Edwin Booth from 1890. He’s standing by the fireplace at the Players, a private social club and still New York’s prestige watering hole for people in the theater business. I always visit it. He played Hamlet, Richard III, Iago, and Brutus and was the most revered American actor of his age. And his brother shot Lincoln.

The Players club was Booth’s vision. He believed that actors ought to mix “with minds that influence the world,” which means rich people, so he bought an 1847 mansion on Gramercy Park and hired Stanford White to renovate it as a clubhouse. It opened in 1888. The club commissioned Sargent to paint Booth’s portrait, which it displayed over its primo fireplace from 1890 until around 2002, when the club, needing a cash infusion, offered it to the Clark Art Institute for $2 million, a steal for a full-length Sargent of a celebrity. At the time, I was the American-art curator there. The Clark owned a dozen or so Sargents but no full-length portrait. The Players wanted its prized picture to go to a museum.

Alas, the Clark’s director and the curator of European art wouldn’t consider it. Wouldn’t even look at it. Though the Clark had great things by Winslow Homer and others, they all came from Sterling Clark. The museum had never bought an American painting. Atop the hierarchy of Clark acquisitions were French, French, and more French. Flemings and Italians sometimes got a place in the sun.

The dealer Warren Adelson eventually bought it. He eventually sold it to the Amon Carter Museum for, I believe, multiples of $2 million.

Might “my thoughts be bloody,” to quote Hamlet, Booth’s signature role? Nah. Win some, lose some. It’s always nice to see Booth’s portrait and to know it has a happy home. It looks fantastic. What a great acquisition. In January, I’ll write a piece about what Texas museums added to their collections in 2023.