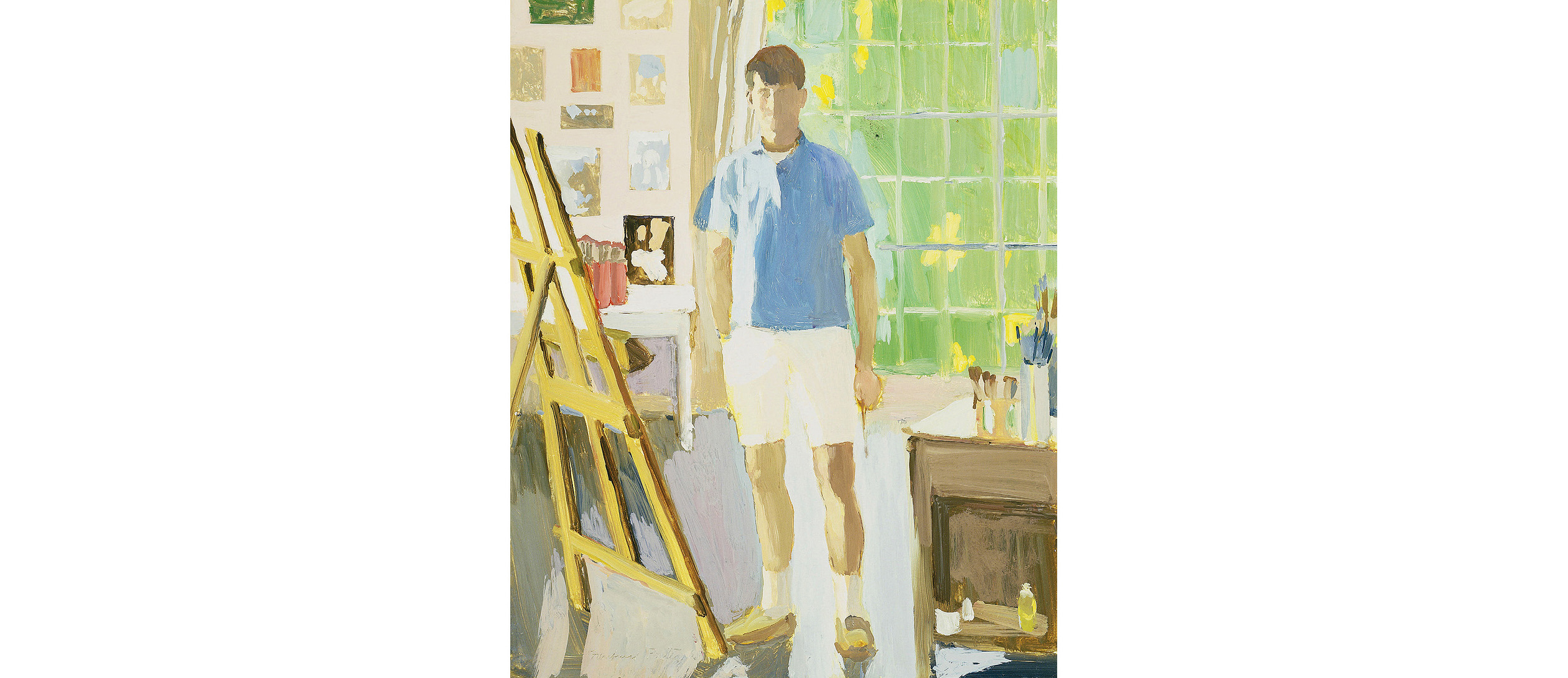

In 1975, Fairfield Porter, A.B. 1928, accepted a commission for the Harvard Club of New York to paint former club president Alfred (Al) Gordon, A.B. 1923, M.B.A. ’25, whose portrait would join those of previous presidents lining the walls. Eschewing the classic portrait style, Gordon said he wanted his own portrait “to shake up the club by giving them something that, in 25 years, might be interesting.” A curator at the Museum of Modern Art recommended Porter, predicting that appreciation for the artist’s work would continue to grow. The painting, featuring Gordon wearing a jacket and tie and seated in the living room of his Gracie Square home, would be one of Porter’s last works: he died of a heart attack on September 18, 1975, the day the portrait was presented at the club.

Porter came from a distinguished Harvardian family that valued creativity. His father, James Porter, A.B. 1895, was an architect; his older brother, Eliot Porter, the photographer, was A.B. 1924, M.D. ’29; and his cousin was the poet T.S. Eliot, A.B. 1910, A.M. ’11, Litt.D. ’47. Fairfield entered Harvard in 1924 and decided, by his second semester, to concentrate in fine art. Even though he received no formal education in art-making, his sole surviving watercolor from those years, “Roofs of Cambridge,” a view across the Charles River to the industrial area of Boston, suggests potential. Porter announced in his senior yearbook that his intended to become an artist.

Upon graduating, he moved to New York to pursue training at the Art Students League, but he left after two years because no one seemed interested in teaching painting. So his mother, Ruth Wadsworth Furness Porter, funded his travel to Europe, where Porter would teach himself to paint by studying old masters. During an extended stay in Florence, he became a frequent luncheon guest at Villa I Tatti, where the art historian Bernard Berenson, A.B. 1887, became his informal mentor. Porter visited churches and museums in Italy, as Berenson recommended, but also traveled to Spain to explore the work of Diego Velázquez, and to museums in Austria, Germany, and France.

Porter returned to New York in 1932, ready to start his career. He married Anne Channing, then a Radcliffe student introduced by family friends, and they settled in Greenwich Village. Both wrote poetry and joined a circle of friends, the “New York School of Poets,” which included John Ashbury ’49, Frank O’Hara ’50, and Kenneth Koch ’48. They introduced Porter to opportunities to write art features and gallery reviews, drawing on his liberal arts education and extensive art-focused European travel. In 1952, when Fairfield Porter received his first New York exhibition, he was hired by ARTnews editor Thomas Hess to write features and reviews of other artists’ work. When a collection of his essays was published posthumously, New York Times art news editor Hilton Kramer hailed it as “the most consistently sensitive and thoughtful writing on new art…that any critic of the time gave us.”

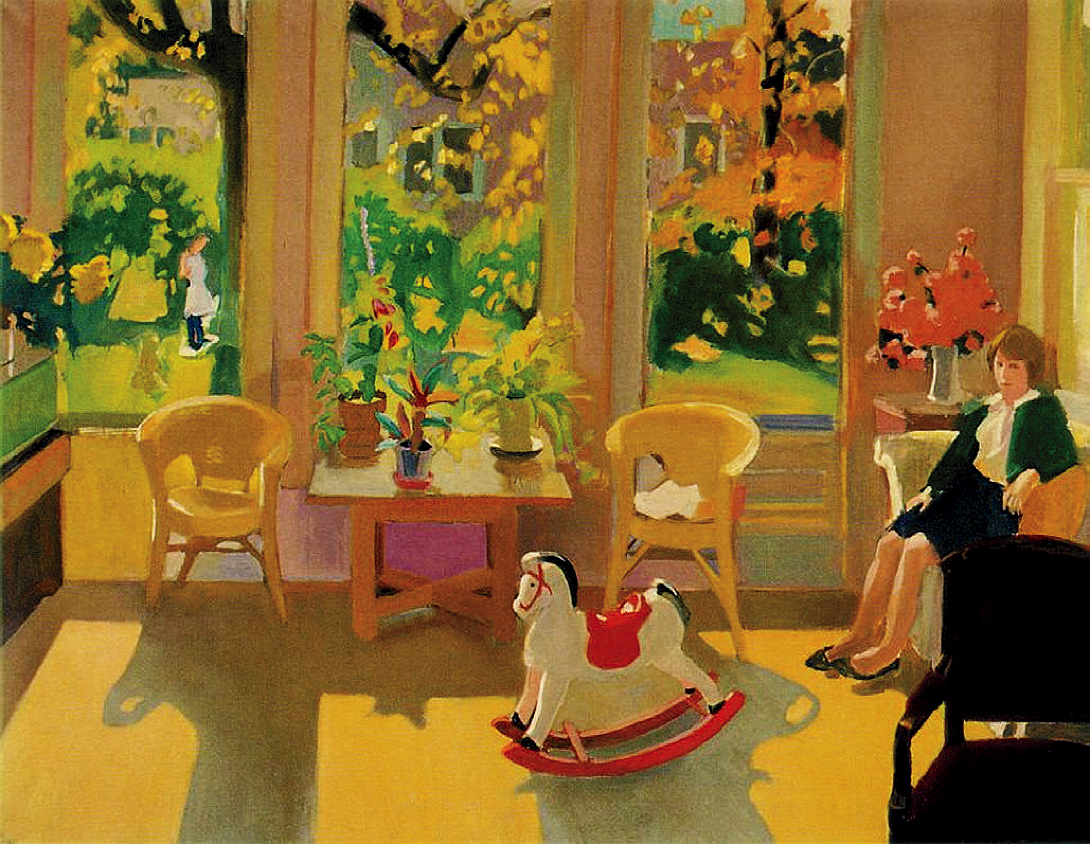

For much of his career, Porter enjoyed greater success as a critic than as an artist. Although his reviews enthusiastically supported the artists of the era’s dominant movements (including abstract expressionism and pop art), he refused to yield to these trends in his own work, painting in a largely realistic, figurative style influenced by his appreciation of late medieval and Renaissance art, the Dutch and Spanish masters, and impressionists and post-impressionists.

Porter painted in the “present tense,” capturing the moments with friends and family: his child practicing the piano, Elaine de Kooning relaxing on the couch, the family dog at the front door. His settings were the places most meaningful to him: coastal Maine, New York cityscapes, and his late Federal-style home in Southampton, N.Y. Noted Kenworth Moffett, Ph.D. ’68, who curated the artist’s first major retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), “His paintings seem ordinary, but the extraordinary is everywhere.”

Success came slowly because Porter’s artwork did not conform to prevailing tastes. He had a following among certain critics, curators, and some collectors, including David Rockefeller ’36, G ’37, LL.D. ’69. Porter influenced younger artists including Alex Katz, who proclaimed, “Fairfield Porter is a painter of great refinement and subtlety. He has a strong technique and a wonderful sense of place…. The realistic world he painted always had a great deal of style.”

Upon Porter’s untimely death, his widow, Anne Channing Porter, committed herself to securing his legacy as an important American artist, donating his paintings to major museums and more than 200 works to the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton. She hoped it would create a catalogue raisonné and ultimately funded the catalogue herself. The MFA’s 1984 retrospective, “Fairfield Porter: Realist Artist in an Age of Abstraction,” resulted in “a sweeping transformation” of the painter’s reputation and status, according to Hilton Kramer.

Today, Porter’s paintings may be viewed at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the MFA, and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, among other esteemed institutions. Surprisingly, there are no Fairfield Porter paintings at the Harvard Art Museums. Surely, there must be space for one from such an accomplished graduate.