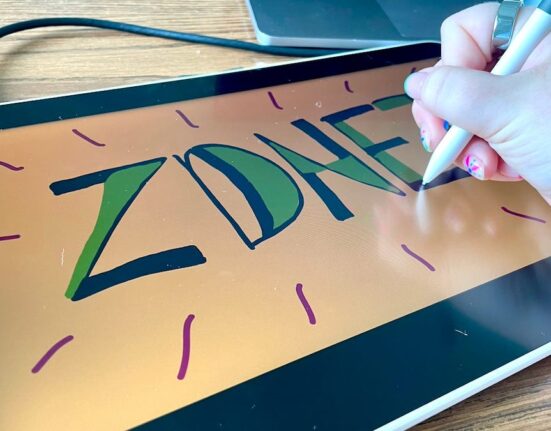

Daisy Parris’s latest artworks are very large and very yellow. The 30-year-old British artist’s forthcoming show at James Fuentes in LA, opening on June 8, will consist of just five paintings, but they are huge—the largest, Your Sisters Deserve Better, is eight feet tall and almost 30 feet across. “I’m just finding painting big so exciting,” Parris says. “The gallery is quite a vast open space, so I knew the work had to be big and bold to hold its own.”

Of course, the paintings aren’t only yellow, but it’s certainly their predominant color—apart from the work Still a Sister, which has a vast pink expanse overlaid with a column of text angrily marching down the middle. “It’s not just a standard sweet yellow,” Parris says, talking from their studio in Somerset, the countryside in England’s West Country. “It almost glows, it’s quite ferocious.” The pink, meanwhile, is “motherly and nurturing but it’s also fleshy and violent.” It’s a bad sign, though, if Parris ever uses mint green. “It symbolizes death for me,” they say. “I don’t know, it just reminds me of a cold, lifeless body, which is really bleak but that’s the association I have had with it since I was a teenager.”

Daisy Parris, Still A Sister, 2024

Courtesy of James Fuentes

Parris’s paintings have an energy that could knock you out. A reviewer from Frieze magazine said of one 2021 work, A Storm the Night You Went, “To stand before it is to confront a vast map of human feeling.” Parris agrees, describing themself as “a very sensitive, emotional person—I feel everything to the extreme.” The new paintings include areas of canvas that have been attacked brutally with a large needle and thread, creating Dr. Frankenstein-like stitches. “It’s quite heavy-handed and clunky, DIY and messy, but that’s the work ethic I’ve been raised on,” Parris says.

Parris was brought up in Kent, southeast England, in an artistic family. Their great-great-great-grandfather was the landscape painter Edmund John Niemann, whose works are in the collection of the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. “My mum was also really good at art at college, and then I guess she had four kids and that took over. I salvaged all of her college work, and it’s all punk and DIY, so that’s where all my influence comes from.” Parris’s father, meanwhile, plays in a band doing two-tone, ska, and reggae covers; the local music scene has been another big influence. “All the musicians”—such as the prolific garage rocker and artist Billy Childish and the folk band The Singing Loins—“were artists as well,” Parris says. “They were designing their own album covers and merch, and then writing books.”

Parris remembers being shaken when their elder sister, now an illustrator, showed her the work of Francis Bacon. “I must have been 12 or 13, and I was just like, what the fuck is this?” The idea that they could spend their days just doing art took them to study at Goldsmiths, in London, which Parris found “hostile and scary… I was from a small town, and I’d just turned 18. I didn’t really have any communication skills.” Parris was painting when most of the other students were making conceptual work, but they refused to be blown off course. “Painting’s always been there for me,” they say. Parris was taken up by the London gallery Sim Smith, and after weathering the pandemic, which descended as they were about to open their first solo show, their work has steadily risen in acclaim. Earlier this year, they were featured in a group show, Present Tense, put on by the blockbuster gallery Hauser and Wirth.

Two of the paintings in the James Fuentes show mention sisters in their titles. “I’m one of four sisters,” Parris says, adding that they also have a stepbrother, “and I’m also non-binary.” The names of the pictures, the artist says, represent them coming to terms with the idea of sisterhood within their gender identity—“sister” as a political expression of allyship as well as denoting a family relationship. “I still show up as a sister, it’s beyond my gender binaries, so that’s what that’s about.”

The text on the paintings usually expresses “loss and grief and survival,” Parris says. “I do the text on loose canvases and then they get chopped up. They go through a lot of editing for me to gain enough confidence to put them in the paintings because they’re quite emotional and honest.” The text on From the Perspective of the End includes the lines “Poem for the rats/Leaves that look like dead mouses/ Screaming sky.” Many of the texts are also influenced by song lyrics. “There’s Typical Days, where I’ve adapted the title Typical Girls by The Slits, so that is looking at it through my lens,” Parris says, referring to the pioneering all-female punk band. “And then there’s Whisper in the Sun, based on Blister in the Sun by Violent Femmes. I’m always writing with rhythm and music in mind.”

Daisy Parris, From The Perspective Of The End, 2024

Courtesy of James Fuentes

Parris has been in her Somerset studio for the past two years, leading what sounds like an idyllic working life. “It’s an old farm building, so there are brick walls, wooden beams, I’ve got lots of natural daylight and double doors that open out onto a field with pigs.” They paint downstairs in the main space and write in a room upstairs. “It’s just stunning,” Parris says. “Obviously, nature and the slower pace of life here have fed into the way I paint now, because I have the headspace and the distance from all the noise to work slower.”

Parris works on up to 10 paintings at a time and doesn’t keep a particular routine. “I’m not an early bird, and even if I am in the studio early, I procrastinate for hours, and then usually just work in the afternoon, from 3 or 4pm onwards.” The process isn’t always enjoyable, but their obsessive focus, and their insatiable urge to communicate, are striking and undeniable. “Painting will always be the consistent thing in my life,” they say, “and I’m committed and devoted to that.”