“I see paintings almost everywhere. Sometimes I’m just walking or watching television or watching a film when this idea appears randomly,” said artist Ian Mwesiga, on a call from his studio in Kampala, Uganda, “It’s this idea that can’t be captured in a moment, but it just passes through and you can feel it in your head.”

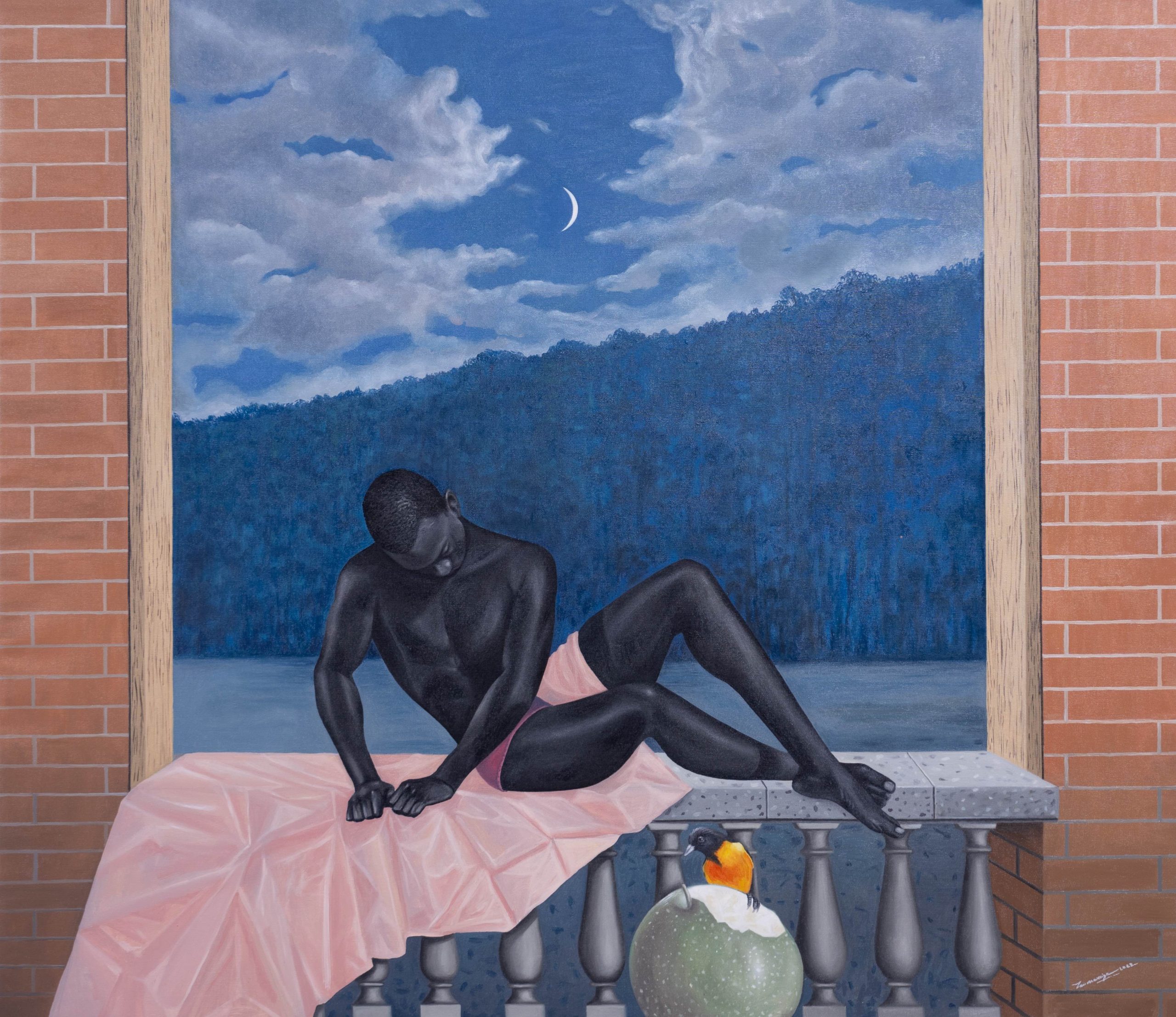

Mwesiga’s recent paintings—metaphysical visions of often solitary figures in uncanny environments—aren’t, in the artist’s estimation, depictions of events occurring so much as distillations of sensations. Eleven of these oil paintings, made between 2021 and 2023, were recently on view in “Beyond the Edge of the World” at New York’s FLAG Foundation (the show closed May 4). The exhibition marked the first institutional solo exhibition for Mwesiga in the United States and one of the first chances for New York audiences to see the rising artist’s work comprehensively (many of the works were on loan from private collections). His paintings have also appeared at many international art fairs including Art Basel, Expo Chicago, The Armory Show, and Paris+ Art Basel.”

Installation view of Ian Mwesiga: Beyond the Edge of the World at The FLAG Art Foundation, 2024. Photography by Steven Probert.

The title of the exhibition, “Beyond the Edge of the World” is a reference pulled from Haruki Murakami’s 2002 novel Kafka on the Shore. In the book, Murakami writes: “Beyond the edge of the world there’s a space where emptiness and substance neatly overlap, where past and future form a continuous, endless loop. And hovering about there are signs no one has ever read, chords no one has ever heard.”

Mwesiga discovered the book while preparing for the show and found a shared sensibility with the Japanese author. In Mwesiga’s paintings, his lonely protagonists appear in misty, unplaceable, and—the longer you look—impossible settings. Incongruous signs appear—a “Dead End” sign stands within a forest or a “No Swimming” next to a shimmering pool with a woman gliding through its depths.

The painter (b. 1988), who earned a BA in Industrial Fine Art & Design from Makerere University in Kampala, has been a rising profile over the past several years. In 2022, the influential gallerist Mariane Ibrahim held a solo exhibition of Mwesiga’s work, “Theater of Dreams,” in Chicago. He’s been included in group shows with the gallery in Mexico City and Paris, too. In 2014, he had his first solo exhibition “Who am I?” at AKA Gallery in Kampala. His works have been shown in Lagos and Nairobi, as well as at international art fairs including Art Basel, Expo Chicago, The Armory Show, and Paris+ Art Basel.

Installation view of Ian Mwesiga: Beyond the Edge of the World at The FLAG Art Foundation, 2024. Photography by Steven Probert.

“Beyond the Edge of the World” highlights recurrent and emergent themes in Mwesiga’s works over these formative few years. The earliest paintings in the show, from 2021, picture long men in blue basketball uniforms (including blue sneakers and athletic socks) in grassy planes—no courts or competitors in sight. In Basketball Player III (2022), a player is suspended mid-jump, ball in hand, over a lake. The body of water appears a bit too wide for a mortal to span, and we’re left wondering about his fate.

Mwesiga describes his painting process as one of constant questioning, drawing, redrawing, and negotiating the canvas. “My canvases are full of uncertainties. I am trying to work out the image and refine, and there are many negotiations and a constant back and forth of trying to reach that fleeting original and imagined idea,” he said. His paintings build one off of the next, in an ongoing conversation.

“My new work is a revision of earlier work, a continuous line of questioning. These revisions are new perspectives and entry points, but the original idea is embedded within the previous work. but transformed in a new dimension,” he explained.

Ian Mwesiga, Tales of the moonlight girl (2023). Courtesy: Courtesy of the artist and Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.

Architectural elements have become an effective way of building these gently unreal worlds. In the work Swimmer and Man standing by the pool (2023), a staircase positioned behind the Hockney-esque swimming pools leads, one realizes, nowhere, recalling De Chirco’s empty classicizing corridors. In Man With Apple in a Pool, a young man stands in a pool submerged to his waist. A sign, a version of the Pepsi logo, bears the strangely ominous tagline “Live for Now.” Magritte is brought to mind, both through the symbol of the apple (one of Mwesiga’s most favored symbols) and through the absurdity of the sign: a swimming pool that’s not for swimming calls to mind Magritte’s iconic Treachery of Images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe). The painting is witty, but also vaguely threatening. One wonders about the safety of this man in the pool, what risk he has taken. Questions of luxury, rest, and race all rise to the surface.

Detail of Ian Mwesiga, Man with apple standing in a pool, 2023. Courtesy of Mariane Ibrahim.

Mwesiga paints his figures in grayscale, rather than shades of brown, giving the works an almost filmic quality, as though they were hand-colored black-and-white images (In an essay accompanying the exhibition, scholar Darla Migan notes that the choice of grayscale hints back to the work of Kerry James Marshall). Blues, meanwhile, hold obvious significance—there are big skies, pools, lakes, and even clothing in various shades of the hue. The palette is reminiscent of Magritte’s skies, but the color also imparts a sense of perpetual stillness to the work. It’s neither dusk nor dawn, though silvers of the moon often appear in the skies. One can imagine the sound of the wind rustling the leaves in a forest or water lapping—but this tranquility also builds suspense.

In the painting, Lying in a Bed of Mist, a woman appears sprawled across a forest floor, asleep or perhaps unconscious. A drink, a tumbler of amber liquid, rests on the ground beside her. A bird, a black-headed gonolek, alights a branch nearby. The bird is a sign of Kapala, a city midway between Tokyo and New York, but also an emblem of Mwesiga’s process, his state of waiting for an idea to flutter through his mind.

Ian Mwesiga, Lying on a Bed of Mist (2021). Courtesy of Mariane Ibrahim.

At times his paintings appear cast as fairytales or ancient stories. The drink beside the woman might be an elixir that has lulled her into sleep. Apples take on similar associations—Eve’s apple or Snow White’s.

“The apple is about seduction,” Mwesiga said. “How can painting be seduction? How can paintings transform and transport someone into the unknown.” But for Mwesiga, his scenes skirt questions of good or evil, here or there. Instead, they live in the heady space of the fantastic, the subconscious, the unrealized. “I never really intend to depict anything as bad or good,” he said, “The paintings are about stretching my imagination as far as I can.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: