It is not common to feel totally at ease in an art gallery, those aloof empty spaces that amplify the sound of your breathing, the thwack of your boots, the sting of the security guard who reminds you when you lean in too close to squint at the descriptive placards. But visual artist, writer and performer sonia louise davis rejects this notion. Inside her warmly-lit Queens Museum studio, where she spent the last year creating the large-scale textile works for her debut solo show ‘to reverberate tenderly,’ the art is plush and inviting, as if it wants you to touch.

I first met davis on a rainy mid-morning in August, before the pieces of ‘to reverberate tenderly’ would be installed inside the museum. “Coming to that title was a journey. Reverberation can mean the vibration inside our bodies. It’s a way for softness, a care for others, a care for oneself,” says davis, who uses the lowercase in her visual art as well as her poetry—her collection slow and soft and righteous, improvising at the end of the world (and how we make a new one) was recently released by co-conspirator press— as an homage to bell hooks and early memories of reading e.e. cummings as a child.

The exhibition — on view from December 6 through April 7 — makes a radical attempt at finding a measure of softness in an austere art world. Here, the Harlem-based artist has created large-scale “soft paintings,” abstract murals made of brightly-colored yarns woven into repeating patterns of curves, dashes and dots. While you can’t actually touch the paintings here, save for smaller samples of them at the gallery’s education station, there will be supervised chances for viewers to play with home-made cymbal-esque instruments installed for live performances. The music davis invites viewers to make will swiftly be absorbed by humble crafting materials.

A city kid who lived near Riverside Park and attended Hunter College magnet schools, davis grew up with creative parents who often brought her to museums. Her father, a writer who took a “thirty-five year break” from his creative pursuits to work a job in market research, has now come back to his art with a bang: The Life and Times of Malcolm X, which he wrote in the 80s and worked on with brother, the composer Anthony Davis, and their cousin and librettist Thulani Davis, is currently running at The Metropolitan Opera. Her mother is a dresser on Broadway; they share the kinship of fabrics. “She works in costumes and, she always says, the glamorous world of laundry,” says davis.

But even though she was often surrounded by artists, davis never contemplated the possibility of art as a formal career path. She left the city to attend college at Wesleyan, where she earned her degree in Black Studies and spent four years singing jazz with a music professor. It’s a practice she somewhat let go of after school—she always preferred the experimentation of rehearsal to the coiffed finality of performing. “That was my first understanding of the power of the singer to go off and make a new melody out of thin air,” she says. “Listening to where the cords are going, what the drummer is doing, everything else is happening.”

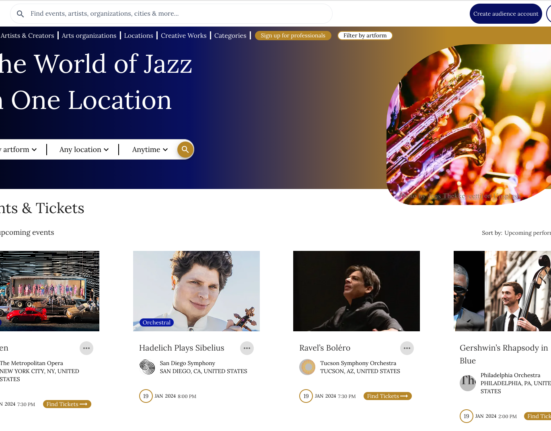

Photo: Sabrina Santiago

She didn’t know it at the time, but the improvisational nature of jazz would later help davis conceptualize her own kind of visual art that wouldn’t have to remain static on the walls. The seeds of to reverberate tenderly began during the early stages of the pandemic, when davis signed up for a one-day tufting workshop. She’d done some weaving before (“I did it on the floor, and I can see why the old ladies have a hunch in their backs”) and craved the physicality of working with fibers after being in “theory land” at the Whitney (where she was part of the museum’s prestigious Independent Study program in 2015, after being selected for the inaugural fellowship cohort of the Laundromat Project in 2011). davis fell so in love with the process that she bought her own machine and got to work. “I was afraid, at first, to get big. I was like, this is a lot of yarn. Maybe I should sketch it out,” she says. But she improvised instead, creating “weird shapes” that invite viewers on both sides. There are no “fronts” and “backs.”

Her soft paintings include “exploded” versions of bright dashes and circles and dots, patterns that she had somewhat absentmindedly started sketching in her Muji notebooks (she still keeps them in her Queens Museum studio) while in the strictures of the Whitney program. “I see them in all these works now,” she says, surveying her workspace. The thin sheets and low stakes of the task reminded her of the kind of physical improvisation she enjoyed as a jazz performer. “I had that with singing. You don’t think at the same time. You have to trust yourself that you’ve warmed up enough to react and respond in the moment. I talk about improvisation and it’s almost preachy, self-care vibes,” she concedes, “But it’s a great teacher.”

Davis works in punchy pinks and other neons. A lot of her yarns are hand-dyed, and in addition to gifted yarn from her mother’s Broadway friends, she works with high and lowbrow materials, from the softer “Michael’s cheapo yarn” to big bags from family-owned stores like Knitty City on the Upper West Side and String Thing in Brooklyn. “Everyone’s having a punny time in the yarn and fiber world,” says davis, laughing. She’s found community in the BIPOC textile community in particular, shouting out Jen Hewett’s This Long Thread, an anthology that crowdsources the experiences of women and nonbinary artists. But Davis is careful about how she defines herself in that space. “I’m toeing this line of using craft technique, but I don’t want to be a crafter,” she says. “I’m in fine art,” she asserts. “I want to fight for the conversation I want for my work. Which table are you at?”

These days, she’s at the table of fine artists who crave haptic relationships with what they’re working on, who want you to walk inside and “get your face up” in the art. Her work situates her along a lineage of Black female artists like Howardena Pindell and Suzanne Jackson, visionaries who work outside of the canvas and don’t shy away from vibrant colors, suturing and sewing with a healthy dose of glitter. “If this is this moment where everything is dematerialized and there’s only machines making all our shit for us, I want to value the hand in something,” she says. “The world is horrible. We need each other,” says davis. “Part of being an improviser is listening. If you’re not listening—” she claps, as if to say, then the show would be over.